Playing it by Ear

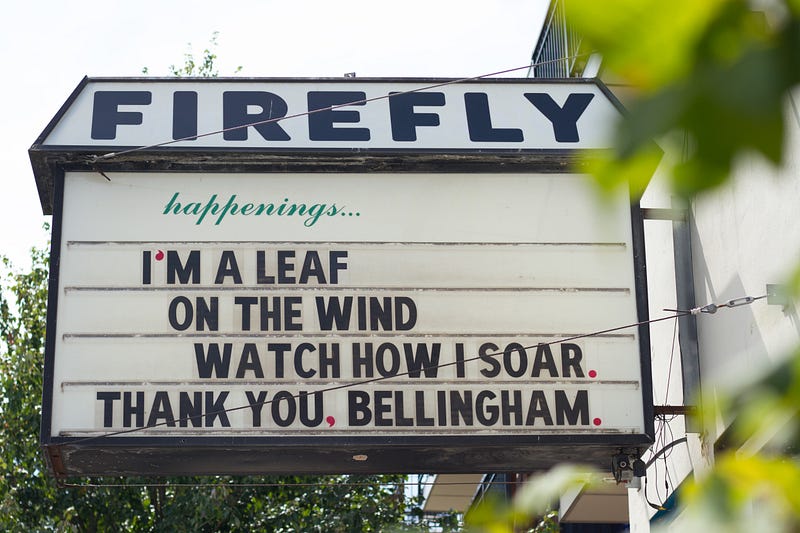

After the permanent closure of The Firefly Lounge, musicians, venue staff and concertgoers imagine a live music scene post-COVID-19.

Story by Riley Currie

“Phew. Wow, everyone, this thing is hard to write.”

On May 23, 2020, venue owner and bartender Erin Gill poured herself a few drinks and sat down to write the 361-word Facebook post that would announce the closure of The Firefly Lounge. The choice to close was already made, but Gill knew sharing it with the public would be hard. She wrote a long stream of consciousness letter in a Google Doc, slept on it, and waited to hit “post” until around 8 p.m. the next day.

Once we hit “send” on this, we’re done, she thought.

For anyone who attended a show or performed at The Firefly, that first line is an understatement. Gill opened The Firefly in April 2018, after taking over the space previously known as the Green Frog in January of the same year.

In two short years, The Firefly established itself as a central venue in downtown Bellingham. The lounge hosted performances almost every night, Monday through Saturday, featuring everything from live music, comedy and open mics to burlesque and drag shows. Sundays were reserved for private parties, touring artists or just a day off.

“We optimistically closed our doors in March, but now, facing an uncertain future … the time has come to close our doors for good,” the Facebook post continued.

As hard as it was to announce the closure, Gill knew she couldn’t drag her feet. She joked that the last thing The Firefly could do for its community was to close early, in the hopes it might help make the impact of COVID-19 on small businesses real to some people.

“For every one dollar spent on a ticket, $12 is spent in the local economy,” Jewell said. “The cultural and economic impact of music venues is so vast.”

The Firefly Lounge employed about 12 people a month, many of them students. As is the case in any venue, staffing was dependent on the show, but employees were always needed at the door, in the sound booth and behind the bar.

The venue was a place for new and established artists, touring acts and tight-knit community events. In the same week, the Firefly might have hosted a comedy open mic, a black metal show, a singer-songwriter on tour and a bluegrass jamboree. The restrictions on public gatherings brought that to a crashing halt in March.

“The decision boiled down to the sheer uncertainty of anything,” Gill said. “We could have weathered a closure of a few months, but when we all sat down and realized it could easily be almost a year, the numbers just didn’t add up.” Estimates are scattered, but most musicians and venue owners agree that concerts won’t be fully possible until 2021 or 2022.

The Facebook post Gill wrote in May received over a hundred comments from patrons and performers alike, lamenting the loss of a beloved space. The responses, heavy with heart and tear emojis, are split down the middle between thank-yous and condolences.

Gill was especially touched by one response, from a regular she remembered saving a table for occasionally. In his comment he said he’d been coming all the way from British Columbia, Canada, for local beer and live music at The Firefly.

“Anywhere people gather for live entertainment — it’s more than just bar sales. The magic of live shows is that it’s all around you,” Gill said.

When concerns around COVID-19 began to spread in March, venues were some of the first public spaces to shut their doors. The National Independent Venue Association (NIVA) reports that 90% of independent venues will go out of business if the shutdown lasts six months or longer without federal relief.

Gov. Jay Inslee issued the “Stay Home, Stay Healthy” order on March 24, which banned “all gatherings of people for social, spiritual and recreational purposes” immediately and officially closed almost all public spaces.

Nearly five months later, venues remain closed. Whatcom County moved to Phase 2 of Washington’s Safe Start plan to reopen the state on June 8, but concert venues and nightclubs are required to remain closed until Phase 4. As counties in Phase 3 experience rising numbers of COVID-19 cases, Phase 4 is being pushed further and further into the future.

For a county that has been in Phase 2 for months, and is now scheduled to remain there indefinitely, Phase 4 seems impossibly far away. For those whose livelihood depends on it, it seems it may never come.

“Without live music or the ability for bands to get together, there isn’t much of a music scene,” said Brent Cole, the owner and editor of What’s Up! Magazine, Bellingham’s music magazine.

Cole started What’s Up! in 1992. Prior to that, he booked concerts and attended as many local shows as he could. This year, for the first time in almost three decades, he hasn’t been following local music.

What’s Up! hasn’t released an issue since March. Without revenue from ads, it isn’t possible to produce a paper. Even if it was possible, there’s no content.

“The cycle of the music scene has glitched and I’m not sure how it’ll play out,” Cole said. He’s worried about the effect a long pause like this one might have on the scene as a whole.

If anyone understands the ebb and flow of a college town music scene, it’s Cole. But with musicians unable to perform, venues facing long-term closures and college plans uncertain, he worries the regular turnover of Bellingham’s music scene might stall.

That worry is felt across the entire local music community.

“I don’t think concerts are coming back until spring of next year,” said local musician and booking intern James Bonaci. “Until there’s a vaccine, it’s not safe.”

Bonaci hopes that the time away from performing will provide space for long overdue conversations about representation and accountability in Bellingham’s music community.

“I hope a lot of people can reflect on what art means to them and why they wanted it in the first place,” Bonaci said. When discussing representation and who is given a platform, it’s important to acknowledge the role independent venues play in the industry. Without an arts community, uplifting artists won’t be possible. “This is a pivotal moment,” Bonaci added.

It’s extremely difficult to survive as a musician without being paid to perform in established venues. It’s even more difficult to uplift previously unheard voices in music without established venues providing that space.

“Musicians don’t make money recording music,” said Craig Jewell, one of the founding members of The Washington Nightlife Music Association (WANMA) and the owner of Bellingham venue The Wild Buffalo House of Music. “They actually lose money.”

The advent of live-streaming has been great for audiences, but it’s not sustainable. Without venues and a live platform, musicians just can’t stay financially afloat.

WANMA was created by a group of independent music venues, local artist organizations, and other music stakeholders in response to the industry-wide economic crisis brought on by COVID-19. The association’s main aim is to provide relief for the Washington music industry.

Jewell is completely focused on keeping live music alive.

“For every one dollar spent on a ticket, $12 is spent in the local economy,” Jewell said. “The cultural and economic impact of music venues is so vast.”

Reopening won’t be as simple for concert venues as it is for restaurants and bars. Most tours have been postponed indefinitely or rescheduled as far out as 2022. The Wild Buffalo has been closed completely since March.

The National Independent Venue Association (NIVA) reports that 90% of independent venues will go out of business if the shutdown lasts six months or longer without federal relief.

“It’s absolutely impossible to predict,” Jewell said of the timeline for reopening. “There was this assumption that it would be two months.”

But as shutdowns crawled into August, that assumption quickly withered. Artists and booking agents stopped confirming dates industry-wide, according to Jewell. This uncertainty comes as a disappointment to concertgoers and as an existential threat to venue owners, employees and artists.

Concertgoers, artists and venue owners are all holding out hope, however. It’s understood that things may be very different when that reopening happens, but for now, all there is to do is wait.

“I see artists using their creativity to keep working on their music, and find new ways to make a few dollars while weathering this shitstorm,” Gill said. “I see a tenacious community, one that’s still making art and will be ready to light up stages again when they can re-open. Mostly, I see a community that will continue to make itself heard, and one that will come out strong when this is all said and done.”

Live music isn’t dead — it’s only sleeping.