Childhood Interrupted

A self-reflection on the high and lows of growing up with Type 1 diabetes

Story by Leora Watson

It was like any other sleepover between two eight-year-old girls. Popcorn, movies, pajamas, snuggling up under a blanket together whispering and giggling. Nothing would have seemed out of the ordinary until my mother came into the living room and hit the power button on our big box TV, turning the room into sudden silence. I will never forget the look on her face as she stood in the darkened room. It was a look of deep distress, a look that was not common for my laid-back mother. We were told my friend was going home and I was going to the hospital.

It has been 13 years since that summer when I was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes, but I can still recall the color of my pajamas as I got into the backseat of our car that would take me to the local children’s hospital. They were pastel green and long-sleeved with a tiny pink bow in the middle of the neckline.

But I was not a witch, I was diabetic.

My sickness came on like a slow burn the weeks before I went to the hospital. It was subtle that I was in ill health. I wasn’t throwing up, burning with a fever or complaining I wasn’t feeling well, common symptoms for a sick child. I drank a ridiculous amount of water but could never quench my thirst. I was lethargic and had low energy, my parents would later disclose to me they thought I was perhaps depressed and missed my friends. I constantly needed to pee, I was losing weight and looked paler than usual.

My grandparents eventually convinced my parents that I needed to be taken to a doctor. It was difficult for my parents to see something was not quite right with me because my symptoms came on slowly and were not dramatic. But my grandparents who were visiting from England and had not seen me for a while could tell something was up. Moments before my mom turned off the TV at my sleepover, my parents and grandparents had been looking at a pediatric care book. My dad remembers going down the list of symptoms in the book for Type 1 diabetes and seeing I had every one. The panic for them probably set in during that moment, but it would be a while for me to fully understand the depth of the situation.

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease where the body’s immune system mistakenly destroys insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. Insulin is a hormone that helps glucose enter the cells of the body so it can be used for energy, according to Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, a non-profit organization that funds Type 1 diabetes research.

Without insulin, glucose cannot get into the cells, so it builds up in the bloodstream and causes abnormally high blood sugar. Glucose is a type of sugar found in most carbohydrates and is absorbed into the bloodstream through the lining in the small intestine. A dangerous complication to having extremely high blood sugars is Ketoacidosis. This is caused when the cells break down fat as an alternate energy source to glucose. Ketones are a byproduct of fat metabolism and cause the blood to become dangerously acidic, according to BeyondType1, an advocacy group for people with Type 1 diabetes.

I was drinking enormous amounts of water right before my diagnosis because my body was trying to flush the ketones and sugar out of my bloodstream resulting in me having to use the bathroom frequently. My body was breaking down fat for energy instead of using glucose, causing me to lose a large amount of weight over a short period. I had no liveliness because my body could not get energy from the food I was eating. Type 1 diabetes is not caused by lifestyle or low activity level and is usually diagnosed in younger children. There is no cure for Type 1 diabetes, and it is a lifelong condition, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

When most people hear the word “diabetes” their mind probably goes to Type 2 diabetes, the more common and talked about form of diabetes. And while Type 1 diabetes and Type 2 diabetes have similar names and share some commonalities, the two are distinctly different. People with either Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes may have a genetic predisposition for the disease. However, Type 2 diabetes is also linked with an unhealthy lifestyle, being overweight, and low activity levels. People with Type 2 diabetes still produce insulin, but the insulin does not work effectively because their cells have become desensitized to the hormone. It is usually diagnosed in adults. People with Type 2 diabetes can use pills, diet and exercise to control their diabetes, according to an article in Healthline.

I was discharged from the hospital after a three-day stay and went to the start of the annual school picnic hosted that same day. My parents did not want my diabetes to dictate my life.

For the first two weeks of school, either my mom or dad was at the school for the entire day, sitting out in the hallway outside my classroom. There was a law requiring a parent to be present at the school with the child until staff and teachers were trained in how to care for children with Type 1 diabetes. Looking back on the situation, I really appreciate that my parents were willing to sit in a school hallway for days on end so I could attend school like the rest of my classmates.

My parents did not want my diabetes to dictate my life.

Being a parent of a child who has Type 1 diabetes is not easy. “It was very overwhelming because there was a lot to learn very quickly,” my mom said. “We did a good job though because you were never admitted again to the hospital.”

If it had been up to me at the time, I would have preferred that no one my age knew I had Type 1 diabetes — I was ashamed and didn’t want my classmates to know I was different from them. But I could not keep it amongst myself and the school teachers and staff forever.

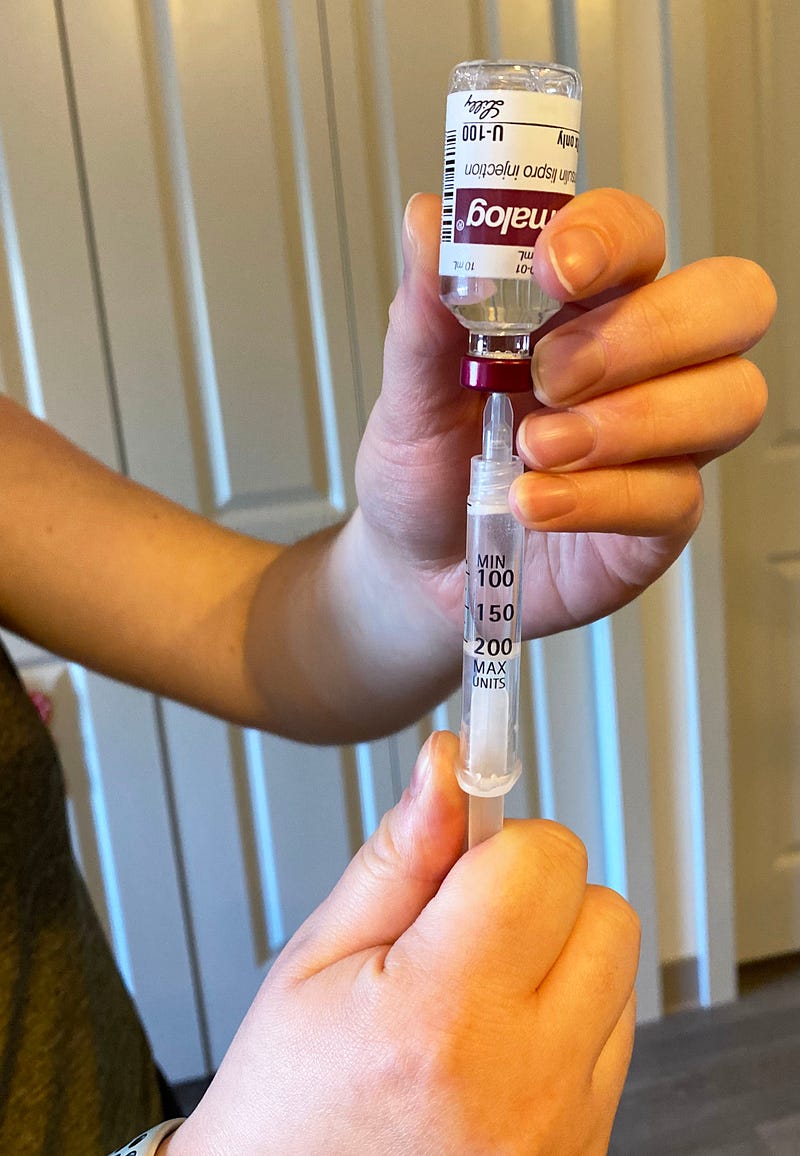

With help from the school nurse, my parents and my teacher, my classmates were told about my diabetes. They were told about how I had to be given shots of insulin when I ate food and to manage my blood sugar. Also, how I had to test my blood sugar throughout the day which required me pricking my finger to draw a drop of blood, and how sometimes I would have to have a sugary food item or drink when my blood sugar was low, even though other students were not allowed to eat in the classroom. Kids peeked back at me as I sat in the back of the group on the carpet, hugging my knees hoping that Hogwarts had forgotten my letter, and I could magically disappear.

But I was not a witch, I was diabetic.

I did not speak once during the whole presentation, but I did demonstrate how a shot was given on a teddy bear named Rufus that had been given to me at the hospital. Rufus was given to children who had been recently diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes and had colorful pieces of felt sewn onto it’s body to show where a shot could be given.

I took a syringe from my bag that sat on a table in front of the class, drew up air and gave Rufus a shot in the tummy, my preferred area for being given shots. The other kids sat there wide-eyed and shocked as I quickly walked back to my spot. I had likely shown them I had to tackle one of their worst fears for the rest of my life. My small body was going to have to be stabbed with needles day in and day out no matter how hard I cried for it to go away.

The panic for them probably set in during that moment, but it would be a while for me to fully understand the depth of the situation

Crying was common for me for a while. Having Type 1 diabetes can be extremely isolating, and it doesn’t help that it is vastly misunderstood and often confused with Type 2 diabetes. One of the hardest situations I would encounter growing up was having to explain to an adult that I was diabetic and that not all rules applied to me. During one particular lunchtime in the cafeteria, I had called my mom with some questions about my blood sugar. One cafeteria attendant had spotted me on my cellphone and started yelling at me that the use of cellphones was not allowed in school. No matter how many times my friends and I tried to explain the situation, it fell on deaf ears.

A few years later, I was kicked out of the computer lab for drinking juice because I had low blood sugar. I ended up sitting in the hallway on the dirty yellow floor with my back pressed against the red lockers. I felt awful as I sat there waiting for my blood sugar to go up.

As a child, you think adults know everything about the whole world, and it became an earth-shattering experience for me at a young age to learn they did not. But I was not the only one who encountered these situations. My parents encountered many as well.

“We had to educate all the adults in your life, like if you were going to spend the night at a friend’s house,” my dad said. “It actually got to the point where we had written up a page that said what to do and gave it to people.”

I am not the only person living with Type 1 diabetes though. Hannah Jones is a Western student and is the leader of the Western Washington University College Diabetes Network Chapter. I met Hannah after joining the group a year ago. Being a part of the diabetes club has been an extremely positive experience for me. To have a group of people who will entirely understand your feelings and frustrations of having to deal with diabetes everyday is like grasping onto a lifeboat in a sea of misunderstanding. I always look forward to our weekly Zoom meetings.

Hannah was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes on New Year’s Eve in 2009 when she was 11 years old after her mother noticed she was drinking more water than usual and going to the bathroom a lot. While Hannah regards her diabetes with positivity and believes it has made her who she is today, she still ran into difficulties.

In 7th grade, Hannah had been invited to a sleepover for a friend’s birthday. The sleepover was going to be at a hotel where everyone was going to go swimming and get dinner together, and Hannah was excited to go. About four or five days before the sleepover, Hannah’s mother received a call.

“My mom got a call from the mom whose daughter’s birthday it was, saying that because I had diabetes I would not be allowed to sleep over, I could spend the day with them at the hotel but I would not be able to spend the night,” Hannah said. Hannah’s mother was upset by this and in the end, Hannah did not attend the birthday party. The friendship eventually ended between Hannah and her friend.

“I look back on it and I give that mom a lot of grace just because she didn’t understand what it was like,” Hannah said. “There’s a lot of misconceptions out there and people not understanding that you can live a perfectly normal life with diabetes.”

Type 1 diabetes has made me face many difficulties throughout my life, but there has never been a moment where I have let my diabetes stop me from doing something I want to do. My hope is that one day everyone will understand what Type 1 diabetes is, but the reality is that will probably never happen.

Technology for diabetes care is always getting better, making it easier for me to care for myself now as a young adult than when I was a child. Over the past few years, I have been working on being more open about having Type 1 diabetes — writing this story was a big step for me. I used to tell no one I had Type 1 diabetes.

I have carried this secret for too long, and it’s time for me to shed that shame. I’m a happy person who enjoys life and I won’t let diabetes dull my shine. And while there are days it makes me want to bang my head against a wall, I will not let it stop me from living my best life. It’s a challenge I am willing to face every day.