The Show Must Go On

How the Bellingham arts scene is striving to keep their lights on amid a global pandemic.

Story and photos by Christa Yaranon

The heart of Bellingham — once bustling with people and buzzing with live entertainment emanating in the streets — has come to a standstill. What were previously music venues packed with concertgoers captivated by local musicians, grand theatres filled with attendees engrossed in a live performance or art galleries displaying paintings and photography pieces are now completely empty.

These spaces, a part of Bellingham’s once vibrant arts and music scene, have long been intertwined with the city’s cultural identity. Now, the marquee lights are dark, the venues collect dust and the art galleries’ walls are bare.

Undoubtedly, the COVID-19 pandemic has silenced the live performing arts scene and has left its future in question.

Nearly nine months after Whatcom County went into lockdown in an attempt to slow the spread of COVID-19, these spaces were the first businesses to shutter their doors with no guidance from the state on when things might return back to normal.

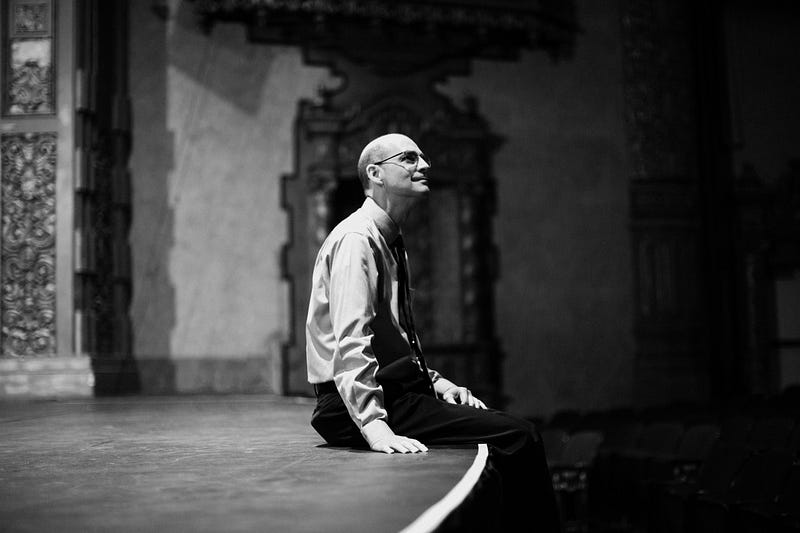

John Purdie, Executive Director of the Mount Baker Theatre, said he was unsure of when exactly that time would be.

“Everything seemed to have evaporated almost overnight,” Purdie said, referencing lockdown orders in March. “We had planned around the stay-at-home restrictions, but once the governor started to extend those orders, it became clear that we were not going to reopen.”

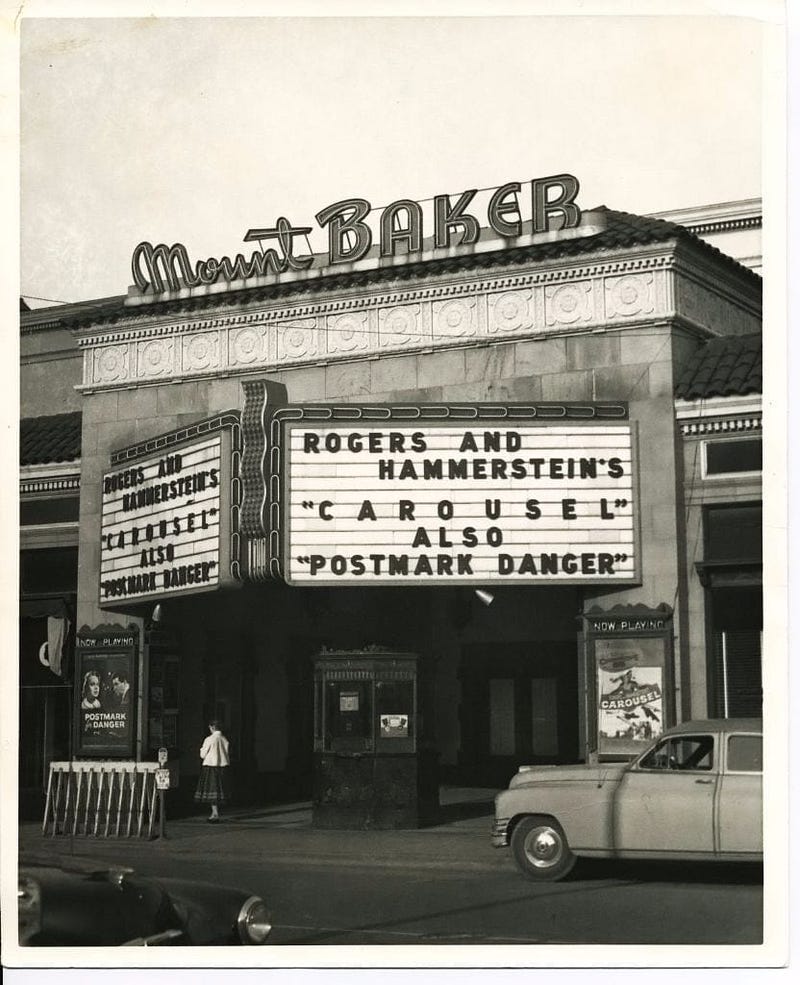

The 93-year-old Mount Baker Theatre has long been a staple to the arts community since it opened on April 29, 1927 and has stood the test of time, having survived eras including the Great Depression, World War II and periods of gentrification where desires for modern and constantly evolving civilizations became more in-demand.

Originally built as a movie palace during the explosion of silent film and vaudeville movie houses, the theatre was established to help distribute silent motion pictures at the height of its popularity in the 1920s.

Known then as a small theatre town with a growing population, Bellingham was targeted as an ideal location for a burgeoning community of movie palaces and became a part of the Pacific Coast vaudeville circuit, where traveling acts that featured singers, dancers, magicians, acrobats and trained animals entertained audiences across the West Coast.

“The circuit traveled up and down the coast to provide arts and entertainment access for a rather rural part of the country at the time,” Purdie said.

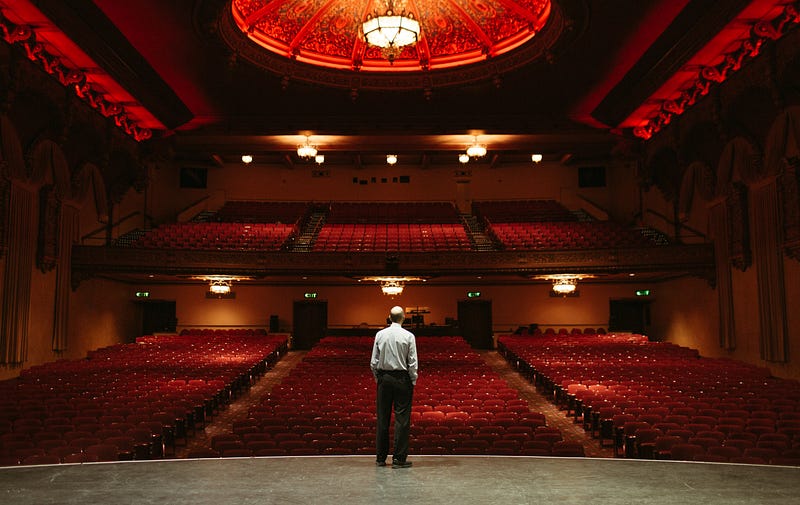

Following architectural design trends of similar movie palaces built across the country, the Mount Baker Theatre resembled the classical look, boasting a luxurious feel that mimicked styles ranging from Moorish Revival, Spanish Gothic and French Baroque. Its attention to form and detail is intricate, with grandiose displays of gold embellishments, Spanish tile and vibrant hues of crimson and jade adorned on its walls, carvings, furnishings and fixtures.

Though the theatre has thrived for decades, the end of World War II signified the decline of movie palaces with the popular emergence of television. Most movie palaces that survived were later converted to performance venues that could operate as theatres displaying concerts, stage plays and operas, which the Mount Baker Theatre had evolved into, according to Purdie.

Now, the theatre remains as the only survivor of five movie palaces originally built in Whatcom County, but has since gone through many renovations.

Despite achieving National Historic Landmark status in 1978, the theatre and its aging facility became reliant on critical repairs, and at one point, came under threat of demolition in the early 1980s. By 1984, community members came together in saving the theatre from being razed to the ground. This coalition had developed an alliance with the city of Bellingham and Whatcom County to create a city-owned facility led by the Mount Baker Theatre Corporation nonprofit.

Today, the Mount Baker Theatre can easily be distinguished downtown, with its iconic 110-foot tower serving as a centerpiece for the city’s arts scene. Memorable performances have graced its stage, ranging from musical theatre icon Bernadette Peters to hometown band Death Cab for Cutie, who all sought the Mount Baker Theatre for a more intimate setting for their shows.

The historic space incubates the artistic scenes and communities that have defined Bellingham as an arts city over the years. From live musicals to rock shows and symphonies, the Mount Baker Theatre’s stage has created a space for artists, both local and touring, to leave their footprints on the city’s arts legacy.

However, with the emergence of COVID-19 and public gatherings now prohibited, the lockdown has forced the theatre’s lights to shut off and the prospect of reopening uncertain.

Employing around 25 full-time employees, the pandemic had drastically reduced the theatre’s staff to three, excluding those who worked part-time, according to Purdie.

Most staffing was dependent on live performances, which left the company with no choice but to have most of their employees go on “hibernation” for the time being. And with the extension of COVID-19 restrictions, Purdie says he and his small team are continuously trying to think of innovative ways to keep the theatre alive.

Part of those prospects includes the screening of holiday films and social distancing precautions planned for late December, since Purdie hopes restrictions could be lifted by then.

Purdie emphasized the theatre’s goals in keeping touch with their community with these film screenings, despite the fact that most of their past events focused on live shows.

“The arts are important,” Purdie said. “We’re giving people a way to escape a few hours of their everyday lives in a relatively safe way.”

Although initially hesitant if the theatre was going to adapt to pandemic norms with livestream performances, Purdie had ultimately decided against the idea, as he thought live performances couldn’t be recreated through computer screens.

“There is a symbiotic relationship between the audience members and with the performer. It’s a three-way circle,” Purdie said. “When you’re in a live performance, the artist feeds off of you. You feed off of the artist, and you feed off of the people around you, and they feed off of you as well. So, because you don’t have that three-way shape of energy flow and interaction, you really can’t replicate that energy when it’s through a screen.”

As Purdie sits amid an empty sea of scarlet red chairs, the walls of the Mount Baker Theatre seem even more cavernous without the crowds and lively energy that pack its room during a usual live performance.

But even with the worries of keeping the Mount Baker Theatre thriving, Purdie stresses the importance of supporting others in the community who are also struggling during the pandemic.

“I think about this arts community which has knit together some close relationships that won’t falter once we get reopened, and it’ll definitely be a huge loss to see if some don’t make it,” Purdie said. “Having our own needs and wants is vital and staying alive is vital.”

Faced with the idea of losing these spaces is a thought Purdie knows will affect the city negatively.

“An arts community is only a community when there’s multiple arts organizations functioning,” Purdie said. “You start to lose some, then you’ll end up losing more until it falls apart.”

Nestled a block north of the Mount Baker Theatre is Make.Shift Art Space, a contemporary all-ages DIY nonprofit art and music venue located in the core of Bellingham’s arts district. The space provides a home base for emerging artists and bands by providing 21 studios, a gallery, a basement live performance space and a low-power radio station KZAX 94.9 FM.

Executive Director Katie Gray walks up a creaky ramp and fumbles through a bunch of keys to unlock the front door of Make.Shift, revealing an empty room that once housed gallery walls decorated with local art installations.

Now, the walls are a blank canvas — a stark contrast from nine months ago when Make.Shift hosted their monthly gallery art walks to a crowded house.

Formed in 2008, the organization’s main purpose was to serve as a support system for local musicians and artists. Spearheaded by a group of friends wanting to provide a creative workshop in the area, Make.Shift had started out as two flagship programs known as “The Magic Van” and the “Power Wheels Program” to aid artists with their endeavors, while also taking a sustainable approach to reduce environmental impact.

“Make.Shift didn’t start off as a physical space, we just had the two programs that bands could use to transport their gear, whether that was for shows or practices, as well as to power our live performances.” Gray said.

For three years, Make.Shift was operated out of volunteers’ homes while on the search for a physical space to call their headquarters. In October 2011, Make.Shift moved into the former Jinx Art Space at 306 Flora St., which opened up more opportunities to hold studio workspaces, gallery showings and live music shows to serve as a community network for local creatives.

“Our biggest goal was to be a stepping stone for young emerging artists,” Gray said. “As far as the way our space is designed, the gallery and the venue are both set up to be a safe place for a band to play their first show ever, or an artist to present their work for the first time.”

But just like the Mount Baker Theatre, Make.Shift had to close its doors in late March when the outbreak had magnified in the county.

Though a setback, Make.Shift had focused its efforts in adapting to the pandemic within a short amount of time.

“Thankfully, from the standpoint of the sustainability of the organization, we’re doing quite stable,” Gray said.

Having adjusted the staff to an online setting, Gray said they were able to quickly transition to a remote environment and had plans to move the gallery and their monthly art walks to a digital presence.

“Our team was able to be on top of that transition,” Gray said. “When the pandemic happened, there was an urgency to adapt the gallery really quickly. We’ve been lucky to adjust our art walks to accommodate this change.”

Further plans include reopening Make.Shift to a complete virtual sense in the new year — including live streamed concerts and continued operations of KZAX 94.9 FM.

“It just took a lot of energy and effort into rethinking how we could continue our shows and our gallery,” Gray said. “In a time where we can’t physically reach people, just to be able to broadcast, webcast and still provide a platform for folks to hear local music and see art when they’re not able to right now is rewarding.”

On a bittersweet ending, Gray’s last few months working as Executive Director will come to a close in December. However, she remains hopeful for Make.Shift’s future, and believes the organization will make it through these trying times.

“I personally have had a lot of feelings of grief. Especially having the goals I had cut short because of the pandemic,” Gray said. “It’s such a weird time to leave a position, and I personally wanted to be there to see it through. Although I’m very excited to know it’s in good hands and that it’ll still be here in 2021, I unfortunately can’t say that for every organization or small business in town.”

Stressing the importance of local art communities in the city, Gray understands other businesses have been hit hard during the pandemic and may face endangerment.

“If the whole scene just collapsed, it would be devastating,” Gray said.

“I know we lost the Firefly, which shut down pretty quickly this year. Things are just so uncertain. I know folks are working really hard to keep these spaces open that are so [fundamental] to our community.”

To Gray, the arts community plays an influential role in defining Bellingham’s own identity, and the city is practically unrecognizable without it.

“I think the creative element really permeates through the whole town,” Gray said. “I mean, you can see it just walking around downtown and seeing murals. Just seeing these little touches of lights, places and people painting through the windows. Bellingham is this little creative town.”

Echoing similar sentiments to Purdie, Gray recognizes the importance of banding together to support other arts businesses in the area.

“I hope that folks realize that it will really take some rallying to save these businesses,” Gray said. “I don’t think we’re necessarily in urgent danger of losing our scene entirely, but I do think folks can’t just get complacent and think, ‘Oh well, I’ll just stay in my house,’ and think they can’t support in any way they can. I think the community needs to be proactive about it.”

What’s on the line is potentially losing these vital spaces that create tangible connections to Bellingham’s arts history and a network that keeps its heritage going for future generations.

“This is all still happening. It just requires a little bit more effort from folks to engage with,” Gray said. “We can’t just walk around our town and think we’ll continue to find this scene once it all settles down.”

Raising the curtains off the windowsill, Gray peers out at Flora St. The evening sun has cast long shadows on Make.Shift’s walls, saturating the room with golden light. A sense of pride and hope is displayed on her face — prideful that she leaves behind a lasting impact on the next generation of Make.Shift’s leaders, and hopeful that the vacant art space will be filled with tenants in its future.

As for the Mount Baker Theatre, the entrance is eerily quiet for a Thursday night. But unbeknownst to most, inside its dark halls — a singular ghost light is left burning on the stage. Patient and incandescent, it will continue to illuminate the empty theatre until live performances transpire once again.