Black Lives Matter Movement Brings Pride Back to its Roots

History of the real meaning of Pride month and its relation to Black Lives Matter Movement

Story by Cameron Sires

COVID-19 has put Pride celebrations in the background and the real issue of racial equality in the limelight, giving an opening to reflect on how the Black Lives Matter movement can reintroduce Pride to an all-inclusive movement, and where everyone can just be who they are, and propel both movements forward.

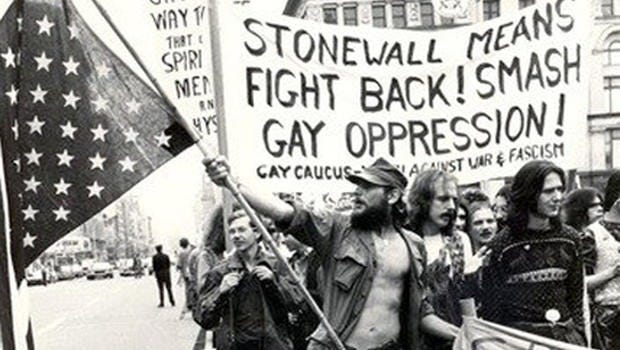

Conflict begets revolution, and historically, movements require digression. Fifty-one years ago police raided the Stonewall Inn, a New York City gay bar in the Greenwich Village neighborhood.

The Stonewall uprising ignited in the early morning of June 28, 1969. The LGBTQ+ community had grown sour over the narrative society had given them. Time and time again they dealt with police raids and were routinely subjected to harassment and persecution. When confrontations with police became violent, the individuals from the LGBTQ+ community put up their fists and began the fight for liberation.

Steven Sawyer, one of the co-founders of Pacific Northwest Black Pride, emphasized the connection between the past violence against LGBTQ+ people experienced to the current Black Lives Matter movement. “Stonewall was about standing up against police brutality and that is what we are returning to,” Sawyer said.

While Stonewall didn’t necessarily start or end the LGBTQ+ civil rights movement, it was the stimulant for sustained political activism. Alike to the current Black Lives Matter movement, the news of this uprising had spread like wildfire around the world after George Floyd was murdered by Minneapolis police officer, Derek Chauvin. People were inspired and wanted a part in this fight for equality.

“Think about how Pride started,” Sawyer said. “A lot of people give credit to Marsha P. Johnson for throwing the first brick of rebellion.”

Marsha P. Johnson, a New York drag queen, was widely known as the poster child of the Stonewall riot. Marsha’s legacy is not only monumental because she pushed the envelope within the LGBTQ+ community, she also became a beacon of light for transgender people. Marsha also engraved the importance of inclusivity within the LGBTQ+ community, especially the Black LGBTQ+ community.

Chris Vargas, executive director of the Museum of Transgender History & Art and speaker at Western’s “50 Years After Stonewall,” has laid groundwork for the recognition of LGBTQ+ people of color such as Sylvia Rivera, Marsha P. Johnson, Miss Major and many others who were great leaders from the Stonewall riots. The Black Lives Matter movement has put a greater spotlight not only on these leaders but also a connection between racial and LGBTQ+ justice.

“I think queer liberation, since its inception, has been intersectional and intrinsically linked to racial justice,” Vargas said. “I see these two linked in the recognition that Black trans people are especially vulnerable to physical and systemic violence and discrimination and deserving of our care and support, and that Black Trans Lives Matter.”

Stonewall produced several crucial organizations that propelled the Gay Liberation Movement forward, including the Gay Liberation Front. This Front was the first and one of the most radical organizations that was a product of the riots. This organization formed a newspaper called Coming Out! which covered topics that educated people not only about gay and lesbian culture but also feminism and race. They also made an alliance with the Black Panthers, whose principles and practices were of Black socialism, nationalism and armed self-defense of Black citizens to patrol police officers’ behavior. This organization had groups in many major cities. This partnership was the first time that an openly gay organization had collaborated with another oppressed group.

“We now understand that Black Lives Matter. The truth was the Gay Liberation Front understood this in 1970,” Perry Brass concluded in his article about being apart of the Gay Liberation Front.

Pride has taken a step back this year due to the pandemic, but it’s allowed Black Lives Matter to take a step forward, and this may be the best thing that has happened to Pride in years. Sawyer emphasized what has happened to Pride is that it has become commercialized in a lot of ways, but during this movement it’s allowed people to reflect and do things differently.

Commercialization doesn’t only pivot the meaning of Pride into a box that multimillion-dollar businesses want the public to see. It also produces a deeper set of problems of how people of color in the LGBTQ+ community are often forgotten in this celebration of an all-inclusive fight for equality.

Inclusivity has been ingrained in Pride’s history; the leaders that built the stepping stones to Pride were racially diverse. “When narratives of our history — for example Stonewall, the AIDS crisis, resistance to erasure of public sex cultures or advocacy for trans-inclusive health care — erase queer and trans people of color, those narratives are historically inaccurate and perpetuate dangerous dynamics of white dominance,” said L.K. Langley, Western’s LGBTQ+ Director.

Terminology within the LGBTQ+ community has also been wiped of diversity. A Longoria, a member who spoke at Western’s “50 Years Since Stonewall” event, said, “When we say, ‘queer,’ sometimes it’s automatically assumed to be signaling white queer, in a way we actually have racism within our own community.”

Pacific Northwest Black Pride saw the lack of inclusivity in Pride and wanted to reinstitute a space where Black, brown and other people of color in the LGBTQ+ community could be represented.

“We really did want to create this space where people can come and be unapologetically queer, unapologetically Black and positively trans,” Sawyer beamed.

From Sawyer’s own experiences he learned that a place was needed where people from diverse backgrounds could be represented. Sawyer grew up in the Deep South with deep connections to the community, he recalls, “As I kind of came into my own sexuality, I started realizing that there were not a lot of places where Black and brown folk could come together and really feel a part of the [LGBTQ+] community.”

When Sawyer moved to Seattle he started to look for this community. Taking over where the last Black Pride organization ended, Sawyer and Autry Bell created Pacific Northwest Black Pride. The two co-founders looked to team up with other organizations in Seattle that also covered issues of racial equity within the LGBTQ+ community.

To Pacific Northwest Black Pride, providing resources and knowledge about issues that circulate within and outside of the LGBTQ+ community is just as, or even more, important than the celebration of Pride. “There is a schedule of classes where we talk about everything from HIV to Black trans issues,” Bell added.

Sawyer smirked, “But we do the turn-up as well.”

The Black Lives Matter movement and Pride are enhancing both fights by bringing back history such as the Stonewall riots. This history is important to give incentive for the queer liberation and modern LGBTQ+ civil rights movement to help embrace the connection between the importance of representing LGBTQ+ people of color.

“It’s not just a moment, but it’s a movement. A lot of people are saying that, but that is the reality.”

“It was an uprising in response to police violence and harassment of the most vulnerable within our community; namely queer people, low-income, houseless and queer people of color,” Vargas said.

The interruption from COVID-19 has forced Pride events to turn to a virtual platform, but this opens an opportunity for diverse voices to be elevated and push Pride back to recognizing marginalized groups within the LGBTQ+ community. Bell quietly piped in over Sawyer’s shoulder, “It really does give us this unique opportunity to step back from commercialism and get back to what is important.”

People from anywhere in the world can jump online and come to any Pride event of their choosing. People who live in a place that might not be accepting of the LGBTQ+ community can now join in and listen to leaders around the world they can relate to and connect with in the comfort of their own home. Longoria said it is important to have LGBTQ+ and LGBTQ+ people of color educators so students can look at a leader who’s open and accepting of themselves, which then normalizes students to do the same. These virtual Prides do just that.

The Black Lives Matter movement has pushed Pride to return to its roots this year. Both movements have elevated each other and nudged people and businesses to reflect on the building blocks that got both movements to where they are today.

“It’s not just a moment, but it’s a movement. A lot of people are saying that, but that is the reality,” Sawyer said. “I think as us LGBTQ folks, we can’t let this time pass without connecting to that movement. Right? It’s a continuation.”

Just the same, the Black Lives Matter movement isn’t a new concept, especially for Black individuals who experience racism every day.

Langley said, “In recent months, many more people have paid attention to Black-led advocacy against police violence and structural anti-Black racism. More importantly, Black people, including Black LGBTQ+ people, have long been engaged in this advocacy.”