Jew-Ish

As I walk through my past experiences as a Jewish woman, I reveal and disprove the common phrases used to discount antisemitism.

Story by Melody Kazel

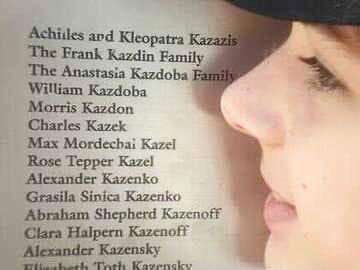

I walk the grounds of Ellis Island.

A metallic plaque, filled with the names of immigrants passing through to the United States, extends across the island.

My eyes scan for a familiar last name: Kazel.

Sun glinting off the metal almost makes me miss them; Rose and Max, my great-grandparents who escaped Ukraine just before the Holocaust — the reason I had any chance of being born.

When telling someone that their comments are hurtful toward me as a Jewish woman, I have received this response: “The Holocaust ended antisemitism.”

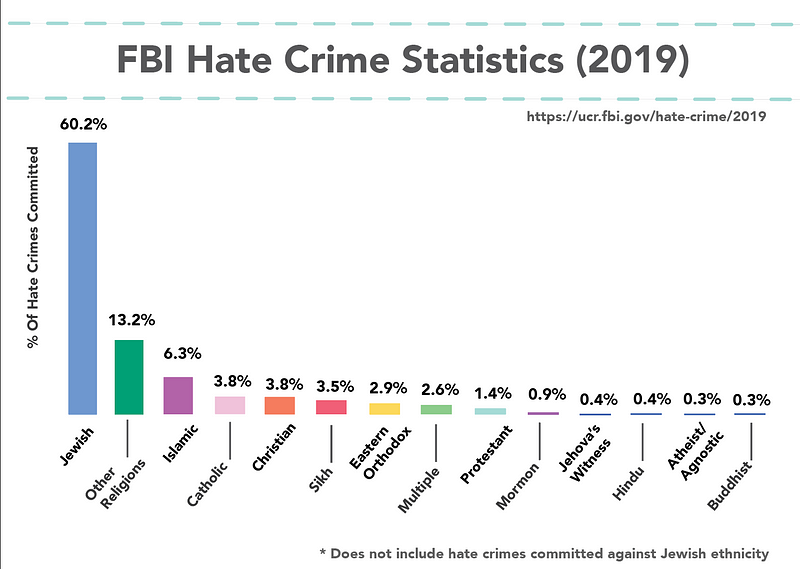

Six million Jews died in the Holocaust. While I have not experienced the genocidal antisemitism that my great-grandparents did, antisemitism continues. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, 60.2% of all reported religious hate crimes in the United States in 2019 were committed against Jewish people. This number increased from 56.9% in 2018.

I place my profile next to their names, Rose and Max, as my mom snaps a photo. I think about how lucky I am to have never experienced hate for being Jewish. I am 13. I do not notice antisemitism directed toward me until I start college at Western Washington University.

In 2019, 11.7% of all religiously-biased hate crimes in the United States occurred on college campuses. This number has consistently fluctuated between 11% and 12% since 2015, according to the FBI. The Anti-Defamation League found that, in 2019, there were 186 antisemitic incidents on college campuses in the United States. The FBI’s data does not account for crimes against people who are ethnically, as opposed to religiously, Jewish.

When telling someone that their comments are hurtful toward me as a Jewish woman, I have received this response: “You are not an ethnicity, so it doesn’t count.”

During the Holocaust, Hitler and the Nazis persecuted anyone who was proven to have Jewish lineage. Why? Because being Jewish is not just a religion. When both of my parents took a genetic ancestry test, their Jewish history appeared. Being Jewish is, quite literally, written into the fabric of our bodies.

The day I heard that a multicultural center was being built at WWU, I asked if there would be a space for Jewish students. People constantly responded by telling me that Jewish is not an ethnicity. No matter how many times I explained that I am ethnically Jewish, people told me I was wrong.

The Jewish community considers anyone ethnically Jewish to be a Jew, even if they do not observe the religion, according to Rabbi Avremi Yarmush of The Rohr Center for Jewish Life-Chabad of Bellingham and WWU.

Jewbu, meaning a Jewish Buddhist, and Cashew, meaning a Jewish Catholic, are just two, among many comical names, for ethnically Jewish people who practice another religion.

There are also people who identify as religiously Jewish who may not be ethnically. However, this group is fairly small, because when someone walks into a synagogue wanting to convert, most rabbis will ask them, “Are you sure?”

Rachel Benezra Devine, a senior at WWU and member of the student board of Hillel, said she experiences confusion from others when talking about Jewish as an ethnicity, rather than disagreement. Most of the time people don’t challenge her about it.

She has been working with the Ethnic Student Center and the Multicultural Center to include Jewish students within the MCC through a partnership with Hillel. Benezra Devine said the club’s goal is to create a supportive space for Jewish students, where they can have conversations about things like antisemitism.

“We want recognition but we also want to be allies for other people,” Benezra Devine said.

The goal of this partnership, Benezra Devine said, is also to extend support and allyship from the Jewish community to other marginalized groups on campus within the MCC.

Benezra Devine has noticed a perception of Jewish people as rich and white, which is a stereotype that can be traced throughout Jewish history.

“[Being Jewish] is not easily defined in today’s Western language,” Benezra Devine said.

She sometimes sees Jewish people as a “hidden minority,” because we often go undetected. However, Benezra Devine said it is also important to acknowledge the experiences of people who face antisemitism for looking Jewish, as well as the experiences of Jewish people of color.

When telling someone that their comments are hurtful toward me as a Jewish woman, I have received this response: “You are white, so it doesn’t count.”

Between 12% and 15% of Jewish Americans are people of color. This does not include information on Jewish people who, while having light skin, are clearly identifiable as Jewish based on their physical features. Jewish people do not fall clearly into one category of skin color, which can lead to them being misrepresented and ignored when it comes to addressing antisemitism.

“The thing that I’ve experienced more than anything is people not allowing you to define, as a Jew, what antisemitism is,” Yarmush said.

I approach the security checkpoint with my dad. His beard has grown so long I imagine him as a wizard from “The Lord of the Rings.” After walking through the metal detector, an airport security officer tells my dad they need to pat him down. They ask for my shoes and swab them for a dangerous residue of some sort.

I want to hide.

The officer hands me my shoes and sends us on our way. This is not the first time we’ve been stopped at the airport.

When I am with Dad, I am treated as a Jewish woman. When I am with my blonde-haired, blue-eyed mom, I am not. While this is a form of privilege, it also means I hear all the hate that a Jewish person both is and is not meant to hear.

When telling someone that their comments are hurtful toward me as a Jewish woman, I have received this response: “You are only Jew-Ish.”

But only I get to make that joke, standing next to my great-grandparents’ names on Ellis Island, in front of my teacher and a class of eighth graders who all think I’m white when I’m just white-passing.

Editor’s note: On Feb. 17, 2021, a correction was made to clarify that the author’s family escaped from Ukraine, not Germany.