If News Could Kill

How a panic attack almost pushed me away from journalism forever.

Story by Dawson Eifert

I was convinced I was going to die.

My heart was beating at what felt like an uncontrollable rate, and my chest hurt, as if I had been stabbed. I was struggling to breathe. I had an impending sense of doom, an expectation of my own demise. I was rushed to the emergency room.

I didn’t have an anxiety diagnosis a few months ago, nor did I have access to the resources I depend on now. I was just a young man taken to the hospital by his girlfriend because he thought he was going to die.

Of course, I wasn’t really dying. It was only a panic attack, an episode of intense fear associated with severe physical symptoms. But I had never experienced one before and had no idea what was happening to me.

About 11% of Americans experience a panic attack every year. Anxiety is the most common mental illness in the United States.

At the hospital, I was placed in an occupied room. A curtain separated myself from the busyness and noise. I was restless. It felt like I had been dropped into a running engine.

After a handful of nurses conducted a series of tests, a doctor stepped in to tell me that I had experienced a panic attack. At first, I didn’t believe him. It was only a few moments ago that I was on the brink of death. This couldn’t have been anxiety, it had to be something else.

The doctor asked us what we were doing when the symptoms of the attack first began.

“We were just watching TV,” my girlfriend said. “The news.”

The doctor nodded. I was annoyed. I mean, give me a break.

This entire incident was caused by the fucking news?

I tried to think back to what we were even watching. It was coverage of the pandemic, a story covering what it was like to work in retail during COVID-19. I began to tense up as I tried to recall the narrative.

The journalist interviewed both retail employees and customers. The workers were exhausted and tired of having to justify the use of facial coverings in a global pandemic. Many of the customers were riled up. Angry. Why are they being denied the opportunity to spend their hard-earned money if they don’t want to wear a mask? It should be their choice, after all.

My chest began to hurt. I was experiencing that stabbing feeling once more. My thoughts began to spiral, a sensation I am now all too comfortable with.

How do these people not see that wearing a mask in a store may be the difference between someone getting the coronavirus and possibly dying? Do they not know that there are literally scientific articles proving the effectiveness of a mask?

My heart started to race.

Does empathy have a place in our society anymore?

I started hyperventilating again. I had worked myself up again to the point of having a second panic attack in my hospital bed.

Yeah, it really was the fucking news.

Prior to this, I had never been admitted to a hospital. It seemed ironic that in the year of COVID-19, it only took basic news coverage for my streak to be broken. In reality, cases of anxiety exploded in 2020.

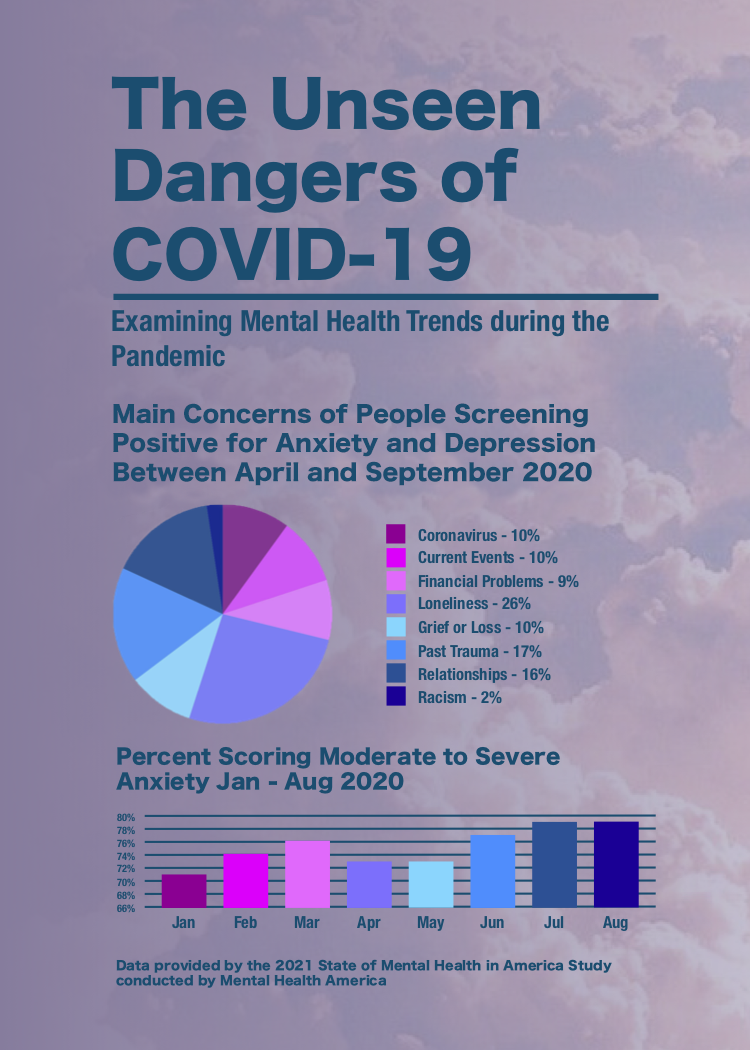

According to an annual report done by Mental Health America, there’s been a 93% increase in those who screened positively for moderate to severe anxiety when compared to the 2019 report. Of those who screened positively for anxiety, 26.97% cited COVID-19 as a primary reason, and 26.79% cited news and politics.

I am beginning to understand my diagnosis.

The doctor asked me about my life, my responsibilities and habits. Do I work? Do I drink? Do I go to school? It would probably be best if I distanced myself from stressful situations from now on.

When I told him I’m a college student, he asked me what I study. I told him I’m majoring in journalism. He laughed.

How am I supposed to distance myself from stressful situations when the news is the center of my education and future career? Am I setting myself up for future visits to the hospital? For failure in a society that lacks empathy?

These are all questions I’ve struggled with since my night in the emergency room. I’ve questioned my major and my career. It’s been some of the most difficult and reformative months of my life.

A few weeks ago, I found myself in a similar position to where I was when I suffered my first panic attack. I was on my couch watching the news with my girlfriend.

It was a story about a doctor erasing the $650,000 debt of one of his cancer patients. I looked up from the game I was playing, engrossed in the story. When it was over, I called my mom so that I could share it with her.

How could someone be so selfless? So empathetic? I thought about the story for a few days.

It had been a few months since my diagnosis. Thanks to therapy and proper medication, I’d been able to get on top of my anxiety for the most part. After being witness to this story of kindness, I was able to remember why I became interested in journalism in the first place.

At times, it may seem like the news only covers stories of disaster, conflict and tragedy. It may seem like it’s a journalist’s job to seek out upsetting stories they can inflict on the world.

However, this isn’t inherently true.

There are positive truths in our society if you take the time to look for them. There is empathy in this world, and there will always be stories of empathy to share, even in a global pandemic.

Providing people with stories they wouldn’t have had access to otherwise is why I want to be a journalist. Truth can take many forms, both in reasons to feel pessimistic and reasons to look at the future with optimism. It’s up to journalists to uncover these truths.

During my night in the emergency room, the doctor told me to distance myself from situations that I may find stressful. I can’t help but feel like that was bad advice. Instead of hiding from what scares me, I’m choosing to seek out stories that inspire me and narratives that make me feel happy. Both as a journalist, and as a young man with anxiety.

I haven’t had a panic attack since.