More Than Just Books

Despite COVID-19 closures, local libraries continue providing resources to their communities.

Story by Riley Kankelberg

I n a lot of ways, Gabe Gossett’s office is exactly what you’d expect from a librarian. Books fill the shelves behind his home office chair. They teeter in stacks that rise from the ground or the table. Libraries have been closed for months, and librarians are some of the many who have turned to remote work in the wake of COVID-19.

On a normal day of in-person learning, Gossett would have arrived at Western Washington University and headed for the second floor. He’d tidy up from the day before and check on the library’s equipment. Then he’d get ready for a day of consultations as head of the Hacherl Research and Writing Studio.

His days no longer look like this. WWU libraries are only open online.

This was the case all across Whatcom County until recently. Libraries, which provide education and resources to their communities, could not allow their communities to come inside.

The WCLS tentatively opened their locations early in November 2020 but closed again at the end of the month due to safety concerns. As of March 1, almost a year after the first round of closures, WCLS locations are open again with modified hours.

Adapting to COVID-19

Christine Perkins is the director of the Whatcom County Library System. This system covers smaller communities outside of Bellingham, Washington. While they share a catalog with the Bellingham Public Library, their 10 locations are separate entities.

When COVID-19 closed the libraries, WCLS made several adjustments to their normal services. Some of those adjustments reflect the basic idea of what a library does.

Gone are the days of weaving through shelves and stumbling across the perfect book you didn’t know you were looking for. Now that people are unable to browse at their leisure, librarians have started crafting “binge-bags.” These can be themed (for example, if you liked “Bridgerton,” you could try a regency romance collection), or you can make a specific request. After scheduling an appointment, you can go to the nearest location and pick up your order through a no-contact curbside pickup system.

Libraries, however, are more than just a holding place for media. Once going inside was no longer an option, the WCLS boosted the Wi-Fi signals in their parking lots so that those living in areas void of service and those unable to afford the internet had a place to go.

For some, it’s the only way to stay updated on the tumultuous times we’re living in.

Deming Library, like other libraries in the WCLS, provides laptops for checkout. On any given day, a familiar truck pulls into the parking lot. An equally familiar woman climbs out. She checks out a laptop and heads back to her truck where a folding chair is waiting. Once her temporary reading room is set up in the bed of her pickup, she opens the laptop and makes good use of the library’s boosted Wi-Fi.

It’s her only access to the internet since March of last year.

“Imagine, how is she getting her news?” Perkins said. “There’s a major pandemic happening and she has no internet, and you would guess she probably isn’t getting the newspaper delivered. How would you know all of the things that are happening around you right now?”

[embed]https://uploads.knightlab.com/storymapjs/567c18b86cd5eba52d08024f2602f351/public-library-map/index.html[/embed]

The Perils of the Digital Age

WWU libraries are also seeing the effects of poor internet connection in a teleworking environment. As an academic library, their audience is focused on — but not restricted to — students. While resources such as academic journals have generally moved online, tutoring and consultations are harder to transition.

According to Gossett, people drop out of Zoom calls fairly regularly. Multiple students using the same Wi-Fi causes connectivity issues. Gossett himself has had his internet go down, cutting him off from students and staff alike.

While meetings and video responses are the preferred methods of communication and feedback, students can fall back on emails and the library’s chat system. Like the WCLS, they offer curbside pickup for physical materials. They’ve also begun mailing materials to people’s homes, something previously reserved for students in off-campus programs.

“The way that I like to describe people who work in libraries is we’re a bunch of nerds for questions and getting people access to information,” Gossett said. “It’s our mission in life. We’re always trying to figure out the best way to do that. Sometimes we actually have to rein ourselves in, because otherwise, we’ll just keep inventing new things.”

Working from home forced a lot of the WCLS staff to move out of their comfort zones and into the digital age. They’ve produced hundreds of videos, ranging from book discussions to informational pieces.

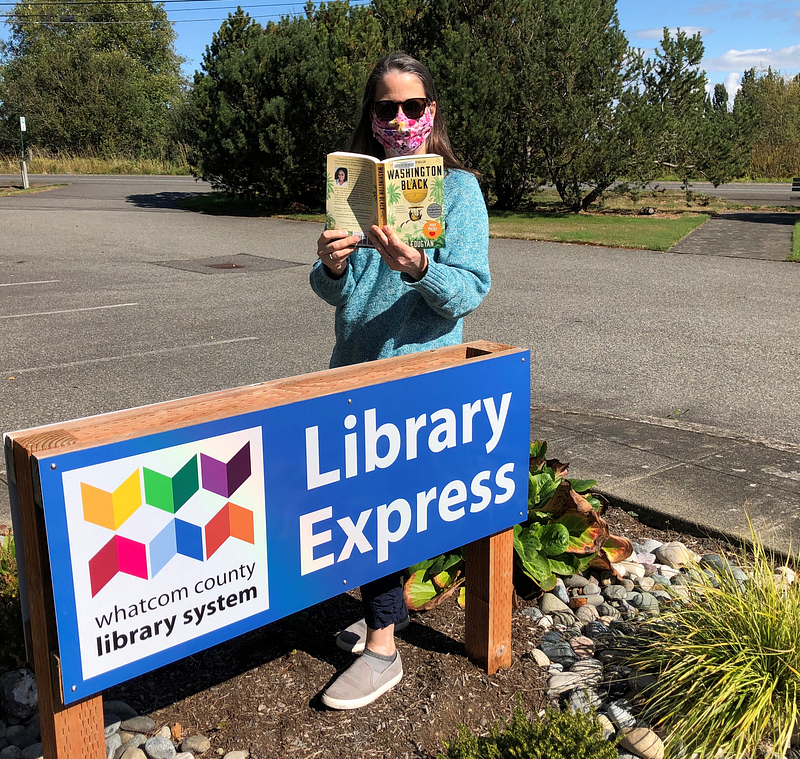

In a recent video, artist Frank Frazee shared his experience participating in the Whatcom READS art challenge. As he read the 2020 selection, “Washington Black” by Esi Edugyan, he kept track of ideas for paintings in the margins of the book. Frazee normally works in acrylics and latex, but the protagonist’s skill with “a stub of a pencil” inspired him to work in graphite instead.

One staff member had taken a class on closed captioning. Once everything went online, they went through their video archives and retroactively captioned them.

“We’ve always wanted to do that,” Perkins said. “We always thought that would be a good idea. We’re all about making things accessible to people with different abilities, but now we have the time to do it and we realized it wasn’t as hard as we thought it was.”

A Sense of Community

Libraries act as a community resource in other ways as well. Events that would have been held in person have become Zoom meetings and webinars. These range from Pajama Storytime, an evening event for ages 2–8, to special events linked to Whatcom Reads.

On a normal day before COVID-19, the Bellingham Public Library could expect to see over 2,000 people wandering the shelves, using computers or attending events. Audiobooks and eBooks were available then, but the demand was nothing compared to now.

Like the WCLS, the Bellingham Public Library does its best to make up for the closure through curbside pickup. Their events, which range from adult book clubs to storytimes for children of all ages, have also gone online. Events aimed toward Bellingham’s younger residents have been particularly well received.

“I know that parents with young children have commented frequently on how much they appreciate seeing the children’s librarians,” said Rebecca Judd, Bellingham Public Library director. “It makes things seem normal again for their preschooler, and their young children are able to build those critical early learning skills.”

On Feb. 5, the Whatcom County Library System hosted “African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle and Song Poetry Reading.” Four Whatcom County poets read selections from Kevin Young’s anthology while providing background on the historic writers.

Shovia Muchirawehondo read “Still I Rise” and “Phenomenal Woman,” both by Maya Angelou. All the presenters were asked to share history on their chosen author, something Muchirawehondo was grateful to do.

“I’m just so glad they asked us to do that,” she said. “I felt like I was able to give the audience substance. I can give you a little piece of the history before I perform, and that puts so much more life into her words even though she’s not with us today. I felt like I was really keeping her alive, more than ever, by how I presented and presented her.”

One of Muchirawehondo’s research methods was to search for a reading by Angelou herself, which she said helped her get even more out of the poems she performed.

The event was held as a webinar, another example of the change COVID-19 has had on daily library life. The poets and event hosts were pictured seated on the screen while the audience members’ cameras remained inactive.

The chat, however, was buzzing. Each poet’s turn was followed by an outpouring of gratitude and congratulations from the audience. During the reading of “Phenomenal Woman,” someone typed, “I love this poem!” Whoever had control of the keyboard clarified that the comment came from an eight-year-old member of the virtual audience.

While this format wasn’t what you’d typically see from a poetry reading, Muchirawehondo thought it spoke to people’s adaptability.

“You have to adapt to survive, and adapting to find a way to still feed your soul is so important,” she said. “It also leads a pathway for the future of participation within a lot of social events or readings. Now you can be in another state, you can be in another country, and this pandemic has kind of globalized our way of communicating.”

A Library’s Responsibility

The American Library Association is a national organization whose goal is “to provide leadership for the development, promotion and improvement of library and information services and the profession of librarianship in order to enhance learning and ensure access to information for all.” Their four strategic directions when providing that leadership include advocacy, information policy, professional and leadership development, and equity, diversity and inclusion.

Gossett has seen a shift when looking at equity, diversity and inclusion during his time at WWU. As head of the Hacherl Research and Writing Studio, he sees it in terms of language oppression. English language learners who write with an accent or dialect might struggle to conform to traditional Western academic writing. According to Gossett, part of the library’s commitment to diversity shows itself in understanding the different ways people express, collect and retain knowledge.

The other place he sees it is hiring. Traditionally, one might see a bullet at the end of a library job ad that briefly mentions diversity. This requirement is difficult to prove. An applicant could say they have a commitment to diversity in the workplace, but the hiring team has no way to measure that commitment.

“We worked with a consultant pretty closely to basically overhaul the whole job ad so it was woven into the actual job description, and it was much more built into the work itself,” Gossett said. “I’ve seen it move from having its first diversity task force to actually trying to build it into all the work that we do.”

According to the ALA’s Diversity Count, last updated in 2012, 88% of credentialed librarians are white while 86% of higher education credentialed librarians are white.

In the spring of 2020, the death of George Floyd sparked protests across the nation. A community memorial was built on the steps of Bellingham Public Library’s central branch. Vibrant bouquets and simple white flowers rested on brick and concrete, leaning against signs reading “I Can’t Breathe” and “Black Lives Matter.”

Soon after that, the library started an anti-racist reading list. The list is made up of eBooks and audio materials, a necessary format due to its unique funding model. The anti-racist reading list is an always-available collection.

Library regulars know the drill. They carve out the time for a trip to the library. They peruse the shelves, sometimes just for the joy of being surrounded by books, sometimes with a specific title in mind. If the title isn’t there, it’s time to check in with a librarian or head to a computer to place a hold. Then all they can do is wait while they climb the ranks of a waitlist.

This isn’t the case for the materials on the anti-racist reading list. Instead of paying the publishers once for the singular copy they’ll keep on the shelves, the libraries pay publishers per checkout.

No holds. No waitlists.

“We couldn’t do that for all of the things we do,” Judd said. “We thought it was really important that people had ready access to those important topics right now.”

Back in his office, Gossett reflected on the way the WWU library has changed with the digital age. As far as he’s concerned, declining circulation numbers are only a tragedy in a sentimental sense.

Librarians are just as necessary as ever to sort through the overabundance of information in the world, and libraries are more than just the books they hold.

“It’s a place where people get to be an individual learner within a community,” Gossett said. “I think there’s so many different things that can happen within a library, but what’s great about it is that each person can make their own journey within that library and within those resources, even online.”