“How Can I Help You Today?”

How service workers have noticed a change in empathy during the coronavirus pandemic.

Story by Garrett Rahn

Downtown Bellingham, Washington takes on a new look these days.

Large portions of the street are now home to an assortment of outdoor seating areas, extensions of the businesses across the sidewalk. Each is unique in its own way, with colorful hangings, brightly painted pallet fences, tea lights galore and heating fixtures to fight the chilly weather.

There are even more changes inside the buildings — scuffed neon tape stripes the floors, a constant reminder to keep a distance from other patrons. Plexiglass shields guard the registers, and plates and platters are a rare sight anymore, replaced with disposable takeout containers and cutlery.

Throughout the city, the experience for both the consumers and the producers in the service industry has undergone massive upheavals to accommodate for the unwelcome presence of the coronavirus.

As time sludges on through the pandemic, people have changed the way they treat service workers in tandem with the new, ever-present danger. With the fundamentals of customer service altered for the foreseeable future, this is the moment to reevaluate what the boundaries of service work are.

It’s rush hour at Boomer’s Drive-in. Fluorescent lights illuminate the cramped backroom of the restaurant. It’s teeming with activity as servers and cooks weave through the narrow corridors between the registers and food preparation stations, carrying out orders as quickly as they can. The smell of fried food drifts across this hive of activity amidst a muddle of voices and upbeat, thumping music.

Lili Gondry, a Boomer’s server, darts between cars taking orders. She makes a mental note of when each car pulls in, so she can greet them in that sequence. The air around her is thick with engine exhaust, and her clothes are sticky and smell like the many milkshakes she has made tonight.

Gondry knows that her customers’ behaviors have changed from before the pandemic to now. She places them into two distinct categories: some customers treat her with more compassion, appreciation and respect, while others come with a heightened sense of entitlement.

“They think that they deserve a lot more than other people do, which is really interesting, because it’s like, what makes you significantly better than the other person who is here to get a burger?” Gondry said.

For Gondry, getting the coronavirus means being out of work and losing a steady paycheck. A big part of a server’s income is the tips they make on the clock, and sometimes customers’ behaviors force Gondry into uncomfortable situations.

“If somebody is not wearing a mask and I don’t feel comfortable, I have to kind of decide right there whether or not I feel like they’re gonna tip me,” Gondry said. “And if they’re not [going to tip], I’m gonna ask them to put their mask on, because I am not feeling like I’m gonna get the money anyways.”

A worker at the local Joann Fabric and Craft store, who wished to remain anonymous and will henceforth be referred to as Ezra, said that very few customers who come into their store follow COVID-19 safety guidelines.

“I feel like a lot of people view you as disposable,” Ezra said.

Ezra witnesses people not wearing masks because they want to drink coffee they brought, as well as customers standing too close to the cashier stands and drifting back up after being told to step behind the line.

Losing their primary source of income is also Ezra’s main concern when it comes to fears about contracting the virus. They are not only frustrated by customers not taking the coronavirus seriously, but also by the way Joann’s doesn’t strictly enforce the necessary precautions to keep their workers safe.

“It’s very hard to play by the rules when it comes to COVID when everybody else isn’t doing it,” Ezra said.

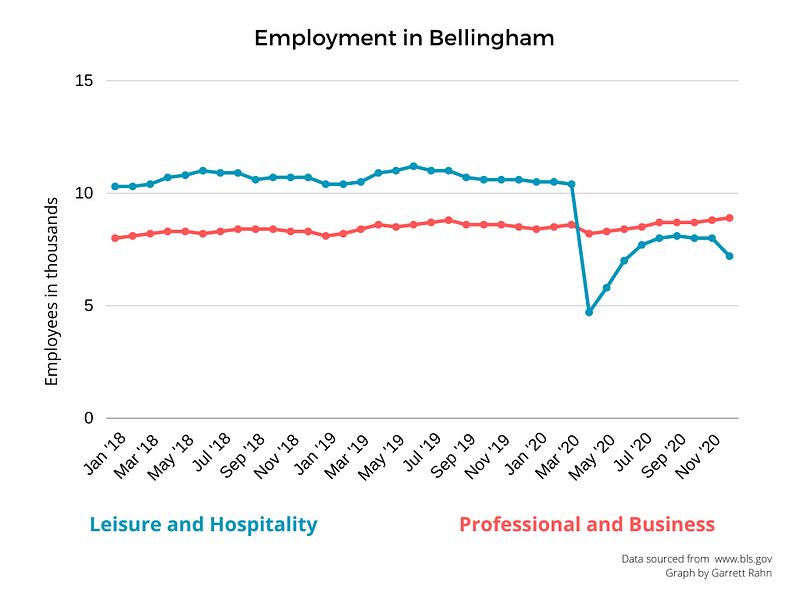

Keeping these jobs despite the health hazards is vital for many service workers, whose jobs in the U.S. were among the hardest hit by the pandemic’s economic toll. Here in Bellingham, we have closely mirrored that national trend.

In April 2020, the city’s business districts stood locked and empty for weeks as its residents sat at home, permitted to leave only for essentials. That month, the Whatcom County unemployment rate hit a historic 17.7%. Businesses within the Leisure and Hospitality sector saw a staggering 55% drop in employment from March to April. There was limited recovery to those figures over the summer and fall, with unemployment getting as low as 6.3% in October. However, the sector has yet to fully recover, and the cooler months have lowered employment further.

Other service industries, such as grocery stores, have fared better throughout the pandemic as people started eating at home more and in restaurants less.

Nestled back in a dark corner of the Fred Meyer parking lot, Elvis Pilgrim stands behind a thick sheet of bulletproof glass in the fuel pump kiosk. He is surrounded by cigarettes and energy shots. The compact space is bathed in yellow light and the faint, pervasive hum of the dusty old ventilation fan.

A customer walks in. He’s not wearing a mask. Pilgrim could ask him to put one on, but knows from past experiences that the request will likely be ignored, or worse, invoke an angry outburst. Pilgrim rings the man up without mentioning it.

That was by no means a rare occurrence. Pilgrim often observes poor COVID-19 safety behavior from the customers.

“It’s a good 50% maybe who wear masks into the kiosk,” Pilgrim said. “I’m not gonna breathe in what you’re breathing, but maybe the person behind you is.”

Pilgrim feels safe in his workstation. He has no direct contact with the customers, thanks to the glass barrier. However, he wishes that people would exercise more caution around other customers and his coworkers inside the store.

“It’s a really scary time for people, and, fuck, man, if all it takes is wearing a mask … just do it. Cause, we’re all in this, but that person [who’s] bagging your groceries or cashiering for you has seen 10 times the amount of people that you have in this one store trip,” Pilgrim said.

Having worked service jobs for a while now, Pilgrim feels like he has a common understanding with the service workers he sees when he goes out shopping.

“This is me — I am interacting with myself,” Pilgrim said. “I think that’s kind of what empathy is, at least in my head.”

Gondry feels she’s been nicer toward people in service jobs ever since she got into the industry. However, she finds it increasingly difficult to be patient with customers when they are rude or incompassionate.

Ezra also tries their hardest to be conscious of how they interact with other service workers. They often try to thank those people and act respectfully toward them, because they know how rare that type of behavior can be. They also stringently follow social distance and mask-wearing guidelines, because of the way the customers at their work treat them.

“It’s just unfortunate when the people [who] you’re talking to very enthusiastically about their next quilting project also don’t seem to see you as enough of a person to social distance from you,” Ezra said.

Many service jobs were deemed “essential” in the pandemic’s inception. But the way that we continue to treat the people who do these jobs tells a different story of how we view them: disposable, as Ezra put it.

Much has changed on the face of the service industry; the tape on the floor, the seating outside. But behind the glass barrier, underneath the mask, they’re still the same people.

Gondry thinks that we all need to be a little more patient with each other.

“No one is trying to go out of their way to do a bad job,” Gondry said.

Understanding that everyone is trying their best, and that you may find yourself in a similar situation someday, can help you make mindful choices around service workers.

The outdoor enclosures, temporary barriers and other building adaptations are mere reflections of something more human. Our perceptions of others have all changed this last year, and going forward, we can choose how that affects our treatment of others.

As more businesses open up going into Phase 2 and the warmer months, remembering our patience might be challenging. But with a little empathy, it doesn’t have to stay forgotten.

On this supplementary podcast, I interview the manager of a local brewery to discuss some of the changes he has implemented over the year, as well as hear some stories of his interactions with customers.