Finding Bravery

Overcoming loss and promoting suicide prevention

STORY BY DANIELLA BECCARIA

photo and photo illustration by Jake Parrish

People have a hard time talking about it — a subject often hushed for fear it may ignite similar thoughts in others. Even when caught up in the tragic aftermath of suicide, opening up to others can be one of the hardest things to do.

For Ian Vincent, a Western alumnus who lost two of his friends to suicide in his first two years at the university, opening up was the only way he could find peace.

“Openly talking about what’s bothering you surprisingly does a lot to help,” Vincent says. “You never really realize that until you’re actually doing it.”

Each year, nearly 1,100 students commit suicide on college campuses in the United States, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. Statistics can help analyze suicide on a larger scale, but when the causes are as different for each person as we are as individuals, addressing the issue can be intensely complicated.

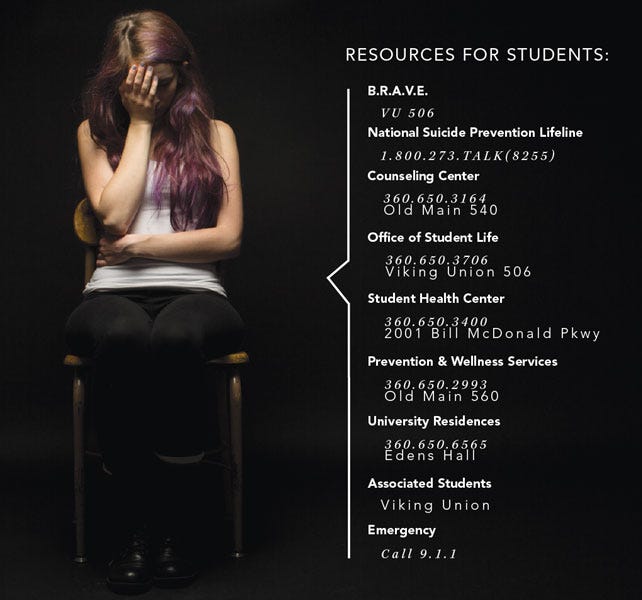

Western’s new suicide prevention program B.R.A.V.E., Building Resistance and Voicing Empathy, encompasses all of the university’s resources into one program. B.R.A.V.E. focuses on helping students who are dealing with depression and suicidal thoughts by giving them the tools to support each other, according to B.R.A.V.E.’s pamphlet.

Vincent began volunteering with B.R.A.V.E. after graduating in spring 2013. He was drawn to the program because of its focus on peer education, helping students recognize signs of depression and thoughts of suicide in others, he says.

After losing his friends, Vincent went through a period of depression as well as suicidal thoughts, he says.

“Being a student, being friends with them, your first reaction is to put a lot of blame on yourself and kind of look at what more you could have done, and family members experienced this too,” Vincent says.

Once he opened up to counselors and friends, he found that the thoughts he was wrestling with were relatable to others going through similar struggles and he felt compelled to help them, he says.

“Originally I was really put off to the idea of going to talk to a counselor about my issues,” Vincent says. “But I found it really helpful.”

When he was first deciding whether or not he wanted to become more involved with suicide prevention he met someone who ended up helping him make the decision.

“We were in class and our professor asked us, ‘What do you want to do after you graduate?’” Vincent says.

Vincent told his professor and the class he wanted to go into suicide prevention because he’d not only dealt with his own depression and suicidal thoughts, but had also lost two of his friends to suicide. Two months after sharing his story, a student from that class contacted him and asked if they could meet up.

“We went out to grab a beer, and I think after 10 minutes of just chatting, all of a sudden he threw out that he himself was dealing with suicide and was literally seconds away from doing it,” Vincent says. “Then [he] thought about what I had talked about in class and realized he doesn’t want to be in that state anymore. He wanted to be able to talk about what he went through.”

The student was struggling with his recovery from a heroin addiction, Vincent says, but was able to share with him how he was feeling. Vincent recalled the classmate telling him, ‘“You being able to go into class and talk about that, I’ve thought about that everyday since you’ve done that.’”

“It really changed my mindset on things and at that moment I realized, ‘OK, I really need to stick with this,’” Vincent says.

In 2013, Western received a $294,948 grant to put toward suicide prevention from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration — an agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The creation of the B.R.A.V.E. program was a multifaceted effort that involved on-campus collaboration from the Student Health Center, Counseling Center, Ethnic Student Center, Veterans Services, Associated Students and Associate Dean of the Woodring College of Education Karen Dade, says assistant dean of students at Western, and overseer for the grant project, Michael Sledge. The program was also created with help from To Write Love on Her Arms, a nonprofit movement centered on helping people struggling with suicide, depression and anxiety.

Since then, Western’s resource centers have been working with B.R.A.V.E. to build a better system for students to recognize suicidal symptoms, Sledge says.

Dr. Farrah Greene-Palmer, Western’s suicide prevention grant project manager, who has a doctorate in clinical psychology, recently started working at Western as head of the B.R.A.V.E. program. Her main goal is to change the perspective on how people address suicide. This includes helping students when they are in emotional distress and not waiting for a crisis point, she says.

“People are used to going to a medical doctor, you know, if you have flu symptoms or heart symptoms, you need to go see a doctor,” Greene-Palmer says. “People don’t always think about, ‘Oh I’ve been sad for a really long time, maybe I’m having these other symptoms more than just regular sadness, and maybe I should go talk to someone.’”

Greene-Palmer has been researching suicide since she was in graduate school at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. She studied suicidal thinking in children and adolescents, and its relation to anxiety symptoms, she says. Her focus is on figuring out how to identify the symptoms before they become a serious problem. Her research also involves identifying protective factors and how to enhance them.

“I’m really interested in the idea that some people think about suicide, and it never gets to the point of attempt,” Greene-Palmer says. “So focusing on what’s protecting them against that even though they are at risk.”

The grant is being used to change bystander behavior — educating students on how to help others who may be struggling with suicidal impulses, Greene-Palmer says.

It has four sections: screening, gatekeeper training, outreach messages and men’s resiliency. Each of these sections is centered on what can be done to more efficiently reach students. In addition, B.R.A.V.E. is reaching out to at-risk identity groups including LGBTQ students, Native Americans, veterans and men.

Since Vincent began volunteering with B.R.A.V.E., he has been put in charge of organizing a few of their outreach events. For Movember, the month of November designated by B.R.A.V.E. as men’s mental health month, Vincent decided to base events off the American Cancer Association’s “no-shave November.” His goal was to bring attention to men’s mental health with a mustache competition, fashion show, two-day mental health fitness fair and the Walk of Hope 5k.

“Don’t forget about the individual in front of you in favor of statistics,” Greene-Palmer says. “Statistics are really helpful when we think about large prevention activities but, while they give some insight into trying to work with an individual, they’re not the whole story.”

For those torn between talking with someone, and keeping the pain to themselves, Vincent suggests just looking into what Western has to offer.

“Dealing from my own experiences, trying to just handle things yourself and ignoring the issue never helps,” he says. “It just continues to get worse and worse for you.”

They sat down at a bar: two students with little connection besides the class they shared at Western. One had a dream of helping people struggling with suicide; the other had been dealing with the nightmare of being seconds away from committing suicide. In the next few minutes, one opened up to the other and sparked a foundation for healing.