Not Your Fault

STORY BY KATELYN DOGGETT

photo illustration by Jake Parris | infographic by Hannah Johnson

Strengthening sexual assault policies on college campuses

THE FOLLOWING STORY CONTAINS GRAPHIC MATERIAL PERTAINING TO SEXUAL ASSAULT & RAPE.

“But you want it, so won’t you at least give me a blow job?” he says while lying on his rumpled blankets, she struggles for anything to say while pinned underneath him. She turns her head sideways attempting to get him to stop kissing her and mumbles something that almost sounds like a “no,” but is not quite audible. Her mind is racing and she forgets how to speak as her black dress bunches up above her waist, as his hand begins moving between her thighs. She closes her eyes and goes to a happy place, wishing she were anywhere but in this moment, refusing to give in to any of his pressuring. After what seems like years, he gets up and angrily leaves, complaining of being led on. She immediately begins to cry, unheard by her two friends, asleep on an adjacent bed.

The night didn’t go as planned. There had been alcohol to celebrate the end of spring quarter 2013, and she thought she made the right decision by staying the night in her friend’s dorm room instead of walking home intoxicated. After falling asleep on the floor, she woke up in her friend’s roommate’s bed, where he was kissing and touching her against her will.

The girl in the incident was me. I am a survivor of sexual assault. While that night’s events could have been more extreme, they happened without consent of both parties. I chose not to report the incident, and for the longest time I blamed myself and wondered if it was even considered sexual assault. I told myself that I had been too drunk and couldn’t remember all the details. Maybe I had led him on because perhaps my dress was too short, maybe I could have done more to stop him. The guy was a mutual friend, and I had always assumed a sexual assault would happen between strangers. I didn’t tell many people about the incident except for a few close friends. Even if I were to have reported it, I didn’t know where to go or whom to turn to next.

Students and educators are working together to change the way sexual assault is perceived on campuses throughout Washington state. Sharing my story is my call to action to change the ideas around sexual assault everywhere.

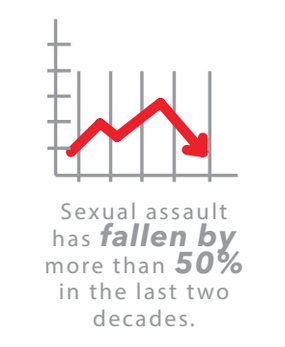

Every two minutes another person in the United States is sexually assaulted, amounting to about 237,868 survivors of sexual assault annually, according to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN). In 2013 only three forcible sex offenses were reported at Western Washington University, according to the Annual Security and Fire Safety Report.

Sexual assault is defined as any actual or attempted sexual contact or behavior with another person without that person’s consent, according to Western’s Policy on Preventing and Responding to Sex Discrimination, Including Sexual Misconduct. Sexual assault includes “Engaging in actual or attempted sexual touching, genital-oral contact, penetration and/or intercourse without consent,” according to the Student Rights and Responsibilities Code.

The new Policy on Preventing and Responding to Sex Discrimination, Including Sexual Misconduct was released in September 2014. The new policy is more comprehensive and includes clearer definitions of sexual violence, says Dr. Sue Guenter-Schlesinger, Western’s Title IX Coordinator. Title IX of the Education Amendments from 1972 requires colleges not to discriminate on the basis of sex.

“Western has been in front of the pack in terms of getting our policy in line with new regulations and we will continue revising it as we need to,” says Guenter-Schlesinger. “We do it because we care about our students, faculty and staff. That’s why Western is interested. Yes it is compliance, but it’s more than just that. You come to school to learn and our obligation is to make sure nothing mitigates that.”

While there are strong policies in place, Western’s reported forcible sex offenses don’t accurately represent the amount of sexual assaults that occur, says Josie Ellison, Western’s representative on the Washington Student Association’s (WSA) new task force for the prevention of sexual assault.

Sixty percent of sexual assaults are not reported to police, according to RAINN. Based on statistics and Western’s enrollment, 406 reports of sexual assault were expected at Western in 2013, according to the Higher Education Accurate Rape Reporting tool, which means 403 sexual assaults potentially happened and weren’t accounted for.

“A lot of folks just don’t think this happens on Western’s campus because we’re such a ‘liberal’ school and we’re so progressive that nobody does that,” Ellison says. “In real life that’s not how it is, and ideas about sexual assault need to change.”

Survivors don’t report sexual assaults for many reasons, Ellison says. Often, the survivor will think the assault was their fault because they may have been under the influence of drugs or alcohol, or because they thought they could have done more to stop it from occurring. Resources, while available, are not readily apparent to survivors, she says, and they won’t want to spend time searching for the next steps of what to do. The survivor will choose not to report the incident because they don’t clearly know the next step, she says.

Sexual misconduct at Western is any ‘unwelcome behavior of a sexual nature that is committed without consent or by force, intimidation or coercion,’ according to Western’s Student Rights and Responsibilities Code.

Sometimes the survivor doesn’t think their experience was serious enough to report, or a survivor has difficulty accepting they were sexually assaulted, says Katie Plewa, Western’s Consultation and Sexual Assault Support (CASAS) coordinator. CASAS provides survivors with emotional support and helps them access all resources available during their healing process including academic support, orders of protection, emergency leave, housing services and judicial services.

“When someone is sexually assaulted, their experience is often inconsistent with what we see in the media,” Plewa says. “We often think of sexual assault happening in a dark alley, perpetrated by a stranger with a weapon. While this happens, it’s much less common. If anyone experienced something that was unwanted and sexual, it’s serious, and they have the right to seek support and/or justice.”

The WSA task force, created in the summer of 2014, is a group of students working to combat and raise awareness of sexual assault on college campuses.

“To me, it’s a basic human right to not have your body violated [sexually] and I’d like to make sure that it’s something that doesn’t continue to happen on college campuses — or anywhere,” Ellison says. “The fact that it’s so prevalent and widely accepted is something I find bothersome and would like to work against.”

The WSA task force will focus on updating the campus culture around survivors, increasing available resources, implementing a way to anonymously report perpetrators and bringing awareness of what sexual assault is, Ellison says.

Starting winter quarter 2015, all students will be required to take an online sexual violence training course, Guenter-Schlesinger says. Currently, the only education students receive is through the Social Health and Responsibility Education tutorial incoming students are required to view. The training focuses on scenarios involving sexual violence, bystander intervention, prevention and consent. It is inclusive to all students of different ethnicities and gender identities, Guenter-Schlesinger says.

Western is home to many groups and resources that all desire to see a change about how sexual violence, and assault, is perceived through educating and supporting students, Guenter-Schlesinger says.

“There are a lot of ideas that people bring to college about what college is all about, norms that aren’t really norms,” says Western’s Empowerment and Violence Education (WEAVE) volunteer Elin McWilliams. “People have false expectations and letting students know that violence and sexual assault aren’t supported at Western is important.”

WEAVE is a peer-health educator group on campus working to empower and educate students about issues including sexual assault and consent.

In addition to the added training for all students and staff, efforts to spread awareness about sexual violence and assault include sending out an email twice a year to all students and staff with Western’s up-to-date policies, placing posters advertising CASAS around campus, responding to input and suggestions from students and in the future potentially advertising resources on KUGS, Western’s radio station, Guenter-Schlesinger says.

Ellison, McWilliams and Guenter-Schlesinger want to increase talk of sexual assault on campus because it tends to be a subject that people avoid, they say. Ellison wants Western to stop perpetuating rape culture, realize that victims aren’t always straight white women and learn how to support survivors. In order for student’s perspective of sexual assault to change, victim blaming needs to end, she says.

Victim blaming occurs when responsibility is placed on the “victim” or survivor for being sexually assaulted, instead of putting it on the perpetrator of the assault, McWilliams says.

“It’s detrimental in our society because instead of focusing on the problem we are focusing on the person experiencing the problem,” McWilliams says. “We are invalidating [survivors] and making them feel like it’s their fault, rather than teaching the perpetrator not to commit acts of violence.”

Victim blaming happens not only on college campuses throughout Washington state and the United States, but also to a larger extent in today’s culture, Plewa says. Many people still believe various misconceptions about sexual assault and will fail to hold offenders accountable when it is never a survivor’s fault.

“We need, want and must develop a culture of caring,” Guenter-Schlesinger says.

Having a clear definition of consent is very important so survivors will know that the school has their back in cases of sexual assault, Ellison says.

Consent at Western is defined as a voluntary agreement to engage in sexual activity. It is informed, freely given and mutual, according to Western’s policies. Other aspects include that consent cannot be given when intoxicated, silence does not equal consent, coercion or force invalidates consent, past consent does not imply future consent and that consent can be redrawn at any time.

Almost two years after I was sexually assaulted, I have finally accepted that it was not my fault, and am willing to speak out about my experience. Even though I wish that night never happened, I don’t seek pity for what I experienced. I do desire a change.

While Western is a progressive campus on its way to changing the way sexual assault is viewed, it’s an ongoing process, Guenter-Schlesinger says.

“Everybody would like to say there’s zero [sexual violence] happening anywhere,” Guenter-Schlesinger says. “But the truth is that we’re making progress. Are we there yet? No. We’re not 100 percent there yet. What is important is that we have the processes in place that we communicate to the public what their options are that our actions speak louder than our words and that the appropriate action is taken. This institution takes things seriously. We don’t want it here.”