On Death and Dying

“The Web We Weave”: A Bellingham Exhibit Starts the Conversation

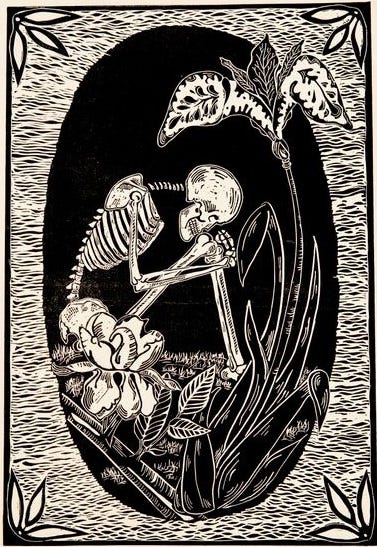

STORY BY RACHEL LOOFBURROW | PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY BEATRICE HARPER

(Above) Candles surround the piece “Letting Go” by Cheri Hepker on a crisp night at Bellingham’s Bayview cemetery. Hepker’s artwork is inspired by the impermanence and transformation evident in life.

Drums beat rhythmically in the background. A woman is told she has cancer. The fates come into play.

A walker is presented to the woman, some coffee, a quilt, an oxygen mask, teddy bear, a paper urn and more. The more she is given, the more overwhelmed she becomes.

More choices, more decisions to be made.

The fates wrap her with tissue paper; her entire body is covered. She is drowning in stress.

This storytelling dance, “The Web We Weave”, is one of many different events at the Art of Death Exhibition, organized by Ashley Benem. 2015 was the second year the exhibition has taken place. She wants people to be able to have discussions about death and explore the topic through art and creative presentations.

“When somebody comes to you with a topic that is taboo or might be a little touchy we just go, ‘oh no, no, I don’t want to talk about that’,” she says.

Benem believes the stigma surrounding discussions of death traces to our media, marketing, television and movies.

“It’s all about being young and healthy and loaded, everything is geared for that,” Benem says. “We think we’re immortal in this country.”

If we do look to an elderly person were praising how young they look, Benem says.

Benem is a death midwife. Her role is to comfort and support patients who are given a terminal diagnosis and their families.

She spent many years in the medical field as an EMT and a paramedic. When she had her son, she felt the need to make a change in her career. She went back to school and became a massage therapist. From there she became a birth doula to help moms and families.

In the last five years, Benem found herself being called upon by friends and family to comfort those who were dying. Her friends knew her to be a supportive person, someone they could rely on in times of need.

Benem had a realization from being called on by several of her friends and family.

“It just really struck me that this is actually what I really needed to be doing at this time in my life,” Benem says. “When you get tapped out to work with the dying, there’s sort of no going back.”

Benem tried to ignore the subject of death for about a year and focused on doing other things. In the end, she kept finding herself working with people who were dying.

She wanted to learn more about the subject. She searched out training sessions, retreats, anything she could find to help fill in the blanks about the dying process to properly support and guide families.

At a gallery in Anacortes she found a multimedia piece that struck her. The piece was by Scott Kolbo entitled, “Sonic Jeremiah”.

There was white butcher paper nailed to the wall. It ran down to the floor. There was a charcoal and ink sketch. A projection was setup and an elderly man appears on the butcher paper.

He walks out to a field and he begins to wobble. He goes down to his knees. The man dies and then crows appear and start trying to lift him up.

First one or two crows show up and then over time more than a hundred are there. Eventually the man disappears and then slowly the crows disappear.

Benem watched this cycle over and over again for 20 minutes. She thought to herself, art can educate people about death and dying; it can open up their awareness.

Benem’s goal is for people to find their own personal truth about what they believe in when it comes to death. This isn’t about what happens after death, she doesn’t want to go there because that’s a more personal subject.

As “The Web We Weave” piece comes to an end, the mythological figure, grandmother spider, intervenes. She cuts away the tissue paper around the woman with cancer.

The woman can now go to the items presented to her earlier and inspect them individually.

This dance represents how the process of dying should not be overwhelming says Benem.

All the services are available to the dying woman, but she only needs to choose the ones that she wishes for her care.

In the end, the woman dies. A man speaks in the background. He asks if you will walk upon the web or become entangled in it.