Undocumented, Undeterred

Western’s Blue Group provides resources for undocumented students

STORY BY ARIANA HOYER | ANONYMOUS PORTRAITS BY NICK DANIELSON | INFOGRAPHIC BY HANNAH AMUNDSON

Editor’s Note: The last names of the students in the story are to remain anonymous

The average college student has to worry about grades, being away from family and the rising cost of tuition. On top of that, undocumented students often have to worry about being deported or not receiving adequate financial aid to pay for tuition on the basis of their undocumented status.

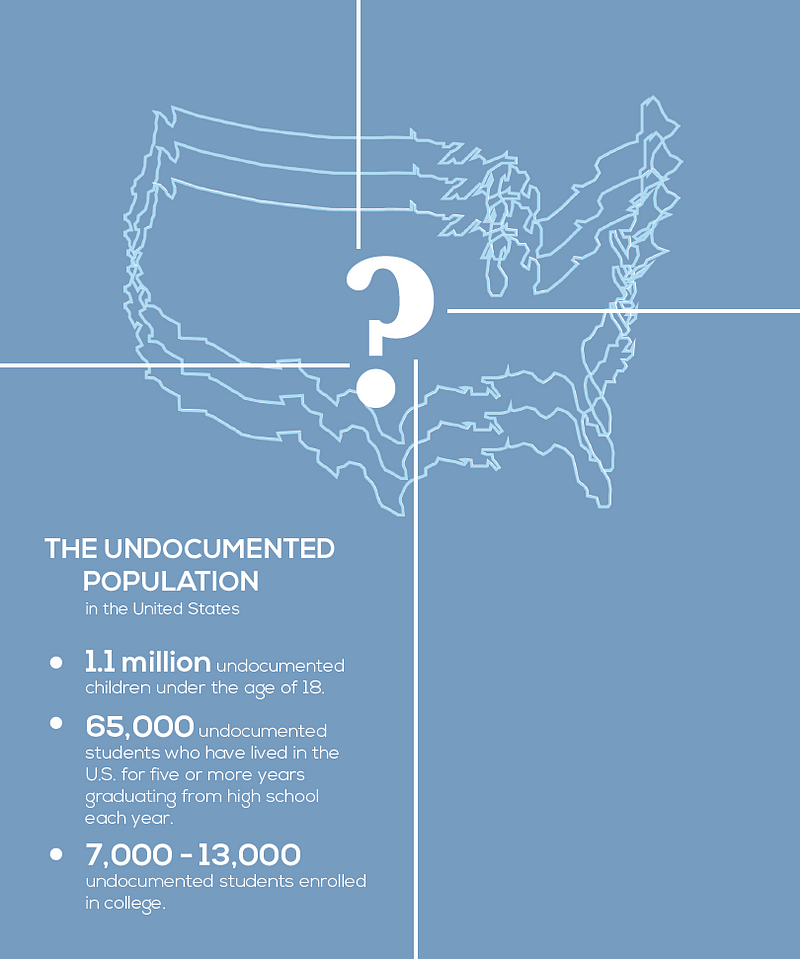

An undocumented student is a foreign national who either entered the U.S. illegally without inspection or with fraudulent documents, or who entered legally as a nonimmigrant but violated the terms of their visas and remained in the U.S. without authorization, as defined by the National Immigration Law Center. The Pew Research Center estimates there were 11.2 million undocumented immigrants in 2012 in the U.S. Around half this population was from Mexico, with numbers declining in recent years.

Between 7,000 and 13,000 undocumented students were enrolled in college in 2012 in the U.S., according to Educators for Fair Consideration. It is difficult to know these numbers for sure because undocumented students are difficult to reach due to their fears of detection.

It is not a federal requirement to be a citizen to access higher education. States and colleges determine specific policies, such as whether undocumented students can enroll at an institution, are eligible to receive financial aid, or pay in-state or out-of-state tuition, according to the UndocuScholars Project by the Institute of Immigration, Globalization and Education at UCLA.

The exact number of undocumented applicants or students at Western is confidential and difficult to determine, Clara Capron, assistant vice president of Enrollment and Student Services says.

Cindy, a Western freshman with an undecided major, and Jarrett, a junior transfer student studying computer science, are two of these undocumented students.

Finding Community and Support

When Cindy and Jarrett came to Western in search of assistance and support, they were directed toward Blue Group, an Associated Students club for undocumented students and allies. Cindy is an active member, but Jarrett has not yet had a chance to attend because of his school and work schedule. Named after Purple Group, the undocumented students club at University of Washington, Blue Group provides support, community and access to resources and services.

“It serves as a community and a place where students can come in and voice their concerns. They just want to be around people who they know and feel comfortable with, who would understand without having to say anything,” Emmanuel Camarillo, Blue Group co-adviser says.

Blue Group helps students fill out the necessary paperwork, such as the Washington State Application for Financial Aid (WASFA) and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), which gives them a valid temporary Social Security for two or three years so they can work. DACA has many stipulations, including age of arrival in the U.S., amount of time in U.S. and year of application and arrival.

Once undocumented students reach college, they find a lack of resources and safe spaces. Students often feel a sense of isolation and uncertainty about whom they could trust, especially with high levels of unfair or negative treatment reported on campus.

“Schools are not prepared enough to consider and take into account all of the different resources undocumented students need in order to be supported and be successful in higher education,” Camarillo says.

Camarillo works with the Blue Group to help create more resources for undocumented students at Western. Workshops, conferences and work with on-campus organizations encourage students to feel comfortable sharing their stories.

The combination of balancing work and academics, high financial need and concerns about their legal status leads to higher levels of anxiety among undocumented students, with 28.5 percent of male and 36.7 percent of female surveyed students’ anxiety levels above a clinical cutoff level, according to the Institute for Immigration, Globalization and Education. This contrasts to the 4 percent and 9 percent of the U.S. population.

The most common concern for undocumented students is the cost of higher education, meaning that nearly 70 percent of these students work while attending college, according to a study by the Institute for Immigration, Globalization and Education at University of California. Students are able to work if they are eligible for the DACA, but it is a lengthy process that requires extensive documentation of one’s time in the U.S.

More than 75 percent of surveyed undocumented students reported worries about deportation or detainment, according to the UndocuScholars Project.

Jarrett

Jarrett came to the U.S. in search of a good education a few months after his 18th birthday, and lived in the Seattle metropolitan area with his aunt for four years before coming to Western this year. He took a year off between his junior and senior years of high school to meet the requirements for in-state tuition.

Washington is one of 17 states that offer in-state tuition for undocumented students, provided that they have lived in state a minimum of three years before graduating from a high school in state. Undocumented students are unable to receive federal aid.

Jarrett’s parents are still in China and send him some money for college, but even with in-state tuition, he is worried about the financial costs of university.

Jarrett does not have the necessary paperwork to be legal, and has additional challenges because he was an adult when he arrived in the U.S. He arrived in 2011, too late to apply for DACA. Without DACA, it is nearly impossible for Jarrett to get a job, he says. He works about 25 hours a week under the table now, making less than minimum wage, but he worries that his status will prevent him from finding a job after graduation.

His hope is to learn and develop skills and wait for a new president or new legislature that will allow him to gain legal status and find employment.

He is soft-spoken and shy, which combined with English as his second language has made it difficult for him to make friends at Western. Though he wants friends, this way he has more time to focus on his studies, he says.

“I study to improve myself. If I can get the knowledge and the skills, I can live anywhere,” Jarrett says.

Though he would be OK moving back to China after graduating, Jarrett wants to pursue graduate school and find a job in the U.S. as a programmer or software developer at a business like Microsoft or Amazon. He’s worried he won’t be able to because of deportation or his illegal status, which prevents him from pursuing his dream.

“I like America. The quality of life is higher. It’s happier here, more relaxed. In China it is very intense,” Jarrett says.

Jarrett worries that if he tells people he is undocumented, they might have a negative perception of him because of his status, but he feels like any other student.

“I think I’m pretty normal,” Jarrett says. “It doesn’t matter if I’m undocumented or not. We are the same. Illegal in status, but not illegal in anything else.”

Cindy

Cindy and her mother crossed the border from Mexico to California when she was six months old; her father had crossed earlier. She is a proud member of the Latinx community, and prefers the term “Latinx” rather than “Latino/a” because it is more inclusive of individuals outside of the gender binary.

Growing up, Cindy was always scared her parents wouldn’t come home at night; that their undocumented status would mean they would be deported. Or even that she herself would be deported.

“There were a lot of high school seniors being deported, so it was hard not knowing ‘Oh, could that be me?’ and just hearing all these stories and all this fear among the community,” Cindy says. “I just didn’t know what all that meant.”

Cindy’s family moved to Tukwila, Washington from the San Francisco Bay area when she was 13, because of increased California anti-immigration laws. In California, undocumented immigrants were not allowed to have a driver’s license.

With the increased anti-immigration laws, businesses started laying off undocumented people. Cindy’s father was a manager, which meant he was responsible for laying off a lot of undocumented people. An undocumented person himself, he knew his time would come, so he chose to resign and moved with his family to Washington, which offers more rights to undocumented people, including licenses and in-state tuition.

Even so, life in Washington was different from what they were accustomed to, Cindy says. Cindy’s parents, uncle and brother lived in a one-bedroom apartment and were reliant upon food banks and the food stamps they received from her now 17-year-old brother. Since he was born in the U.S., he is the only person in her family who is a citizen.

A first-generation student, Cindy’s financial worries stand in the way of her academic success. She was not eligible to receive WASFA this year because of settlements her parents received for the house they left behind in California and her father’s lost wages after being paid under minimum wage. She received some scholarships and work-study this year, and will have WASFA next year, she says.

She doesn’t want to put her parents through the financial burden of higher education. Even though her parents have always encouraged her to pursue college, there came a point where there wasn’t anything they could do but encourage her, since they’ve never gone through the process.

Cindy hopes that after graduation she can work with marginalized youth to be the person for them she needed when she was younger, to provide support and empowerment and eventually create institutional change, she says. She’s not sure how she will do this, because though she has DACA, it’s temporary, and there is no long-term alternative.

Creating Change

Currently the Blue Group is working with the Counseling Center to help them best support undocumented students through the unique challenges and anxiety they face.

Cindy and another Blue Group student recently went to a Counseling Center staff meeting, where they shared their stories and expressed their needs as a community. The goal is to build a trusting relationship between the Blue Group and the Counseling Center where the Counseling Center can meet the needs of undocumented students in a culturally sensitive and culturally specific way, Shari Robinson, Counseling Center director says.

“There’s a lot of trauma that we don’t really talk about because we’re always told not to talk about our status, so it’s something that I feel like the community hasn’t dealt with,” Cindy says. “Even being Latinx, there’s stigma that comes with talking to a mental health professional. We’re trying to change the stigma and also heal ourselves by talking to professionals.”

The stigma and concerns of undocumented students have only increased with the upcoming election and the hateful rhetoric of some of the candidates toward undocumented immigrants.

“The major challenge right now in society in general is trying to understand who they are and understanding that they are also people,” Camarillo says.

With the support of communities like Blue Group, Jarrett and Cindy are able to overcome these obstacles and achieve success.