Banking on plasma

Plasma is in high demand, but controversy remains on payment for donations

STORY BY YVONNE WORDEN | PHOTOS BY KJELL REDAL

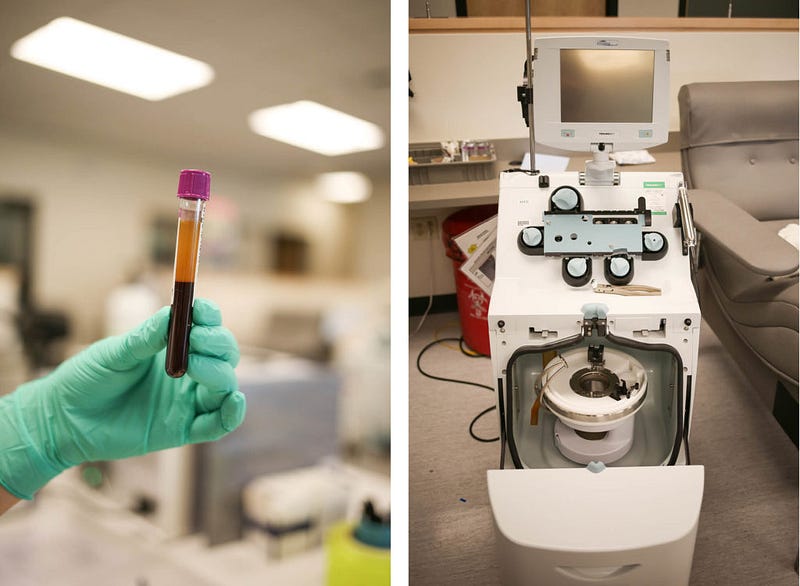

More than 30 beds at Bellingham’s BioLife Plasma Services Center are occupied. Behind visored facemasks, staff monitors lines of plasmapheresis machines. Cylindrical devices in the machines swirl, as red and white blood cells and platelets are separated from yellow, liquid plasma. Donors pump their palms to provide a steady flow of blood to the machine. Once the process is complete, they’ll be paid for their plasma.

Every year, more than 1 million people receive plasma therapeutics, which requires 22 million liters of plasma, according to the Plasma Protein Therapeutics Association. While some say the pay-for-plasma model jeopardizes the safety of the blood supply, both donors and patients rely on plasma donation.

Plasma is used to help patients diagnosed with hemophilia, a genetic bleeding disorder, and immune deficiency. Plasma treatment is also used for people suffering from shock and burn.

There are 82 BioLife centers in the U.S. Depending on location. Students account for up to 60 percent of each center’s donor base. The BioLife Center in Bellingham is a popular cash stop for students from Western, Whatcom Community College and Bellingham Technical College. About 2,000 people sell their plasma per week, necessitating a staff of almost 70.

BioLife Plasma Services is part of Baxalta Incorporated, which develops medical products. Lauren Branch, regional marketing director for Baxalta, says students are loyal donors.

“A lot of students, especially those who have more demanding majors and aren’t really able to work and want to keep up their grades, donate so they have income while they’re in school,” Branch says.

It takes 1,000 successful donations to supply one patient’s year supply of treatment requiring plasma. Because of FDA and the EMA safety regulations, people must donate twice before their plasma can be used and they become a “qualified donor.”

First-time donations take about two hours, including a physical health exam. Donors must be at least 18 years old, weigh 110 pounds and have proof of identification and local address. For each visit, donors take a health questionnaire and have their finger poked to check their iron levels and hematocrit. People are encouraged to eat high-protein, low-fat meals and drink plenty of water before donating.

Once plasmapheresis is completed, donors receive are compensated $30 or $40 per visit. New donors can receive up to $50 for the first few visits, and a “Buddy Bonus” adds $20 to someone’s donation if they bring a friend. People can sell their plasma twice a week, but must wait at least 24 hours between visits to give their body time to regenerate plasma. They can only donate whole blood every 56 days.

The pay-for-plasma model has a questionable history. The Tainted Blood Crisis in the 1980s is considered one of Canada’s worst medical events in history. As many as 30,000 people were infected with HIV and hepatitis C, many of whom were hemophiliacs, who became sick through blood transfusions and plasma products.

The contaminated blood products were imported from commercial operations in the U.S., according to the Krever Commission. Much of the supply was from at-risk populations, including IV drug users, prisoners, homeless people and homosexuals. The crisis was also caused by inadequate HIV testing. Fear of another blood crisis exists today.

Community blood centers like Bloodworks Northwest does not pay for whole blood or plasma. Bloodworks Northwest serves 90 hospitals in Washington, Oregon and Alaska.

“When people are getting money for collections, they may have an incentive to be dishonest on their questionnaires in terms of their medical history or travel history,” Dave Larsen, Communications Director of Bloodworks Northwest says.

The FDA requires paid or donor labels on blood products. Blood from paid donors cannot be used in hospitals, which only accept voluntary blood. Larsen says donating at community blood centers may have a more local impact than donating at private plasma centers.

“You’re supporting your local hospitals, patients, your friends, neighbors, family and your local community,” Larsen says. “You are helping your community sustain its own blood supply.”

Plasma from centers like BioLife are used for medicine or therapy to treat diseases. Larsen says for-profit centers have found a place in the market.

Those with HIV, hepatitis or other transferrable diseases are prevented from donating at plasma centers. Just in case, samples are tested after collection. Branch says it’s important to maintain the number of plasma donors in order to meet demand, even if that means paying them.

While whole blood is mostly collected for medical emergencies, such as car accidents or surgeries, plasma treatment is used on a consistent basis. In severe cases of hemophilia, patients may need treatments every week, Branch says.

“Honestly, even now with all of the centers we have, there’s not enough plasma out there,” Branch says. “Because there’s a big number of people donating plasma for money, if we weren’t paying them, that would probably in increase the need for plasma even more.”

Bloodworks Northwest has found ways to increase donors without paying them. In February 2016, Bloodworks Northwest and Boundary Bay Brewery teamed up for a “Pint for a Pint” drive. Boundary Bay Brewery provided Bloodworks Northwest with vouchers for donors, as a way to say “thank you.” Since the vouchers were donated from Boundary Bay to blood donors, the blood didn’t need to be labeled as paid.

Bloodworks Northwest attracted more than 200 donors during the weeklong drive, while they typically average 80 donations per week, Jason Hess, the Puget Sound North Area Manager at Bloodworks Northwest says.

Many people ask if BioLife takes potential donors away from blood centers. However, BioLife is not competing with community blood centers, Branch says. Both blood centers and plasma centers need a great supply of donations. Donating at plasma centers may heighten someone’s awareness of the importance of donating blood. Branch says whichever one they decide to do; they’re helping save someone’s life.

The plasmapheresis machines beep every few minutes as people finish their donations. Staff wheel their carts over to the finished donors and remove their needles, ending the 45-minute plasmapheresis process. They’ll occasionally ask the donors what they’re doing that night, or how they might spend their plasma money, but they’ll always encourage donors to come back.