For The Love of Jazz

Western Student and musician Rebekah Way reflects on the bonds created through music.

STORY BY REBEKAH WAY | PHOTOS BY DAISEY JAMES

“Name all of the instruments you can hear,” instructed the music teacher at my elementary school. A trill of a clarinet began and flurried into one of the most timeless melodies that blasts classical music with jazz: George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue.”

The melody begins delicately, but then the brass section enters with a crash, and the piece takes off. With several mood changes and intense piano solos, the composition never lost my attention.

Hoping to play music this fiery, I learned clarinet in fifth grade and joined band. I continued into middle school and decided to pick up alto saxophone after watching the jazz band perform a few times.

I learned the blues scale and the one jazz song in our exercise book in hopes of successfully auditioning for jazz band near the end of seventh grade. It was there that I met the people I’d be playing music with for the next six years.

Our first task was to learn “Take the ‘A’ Train” by Duke Ellington, the first of many Ellington compositions we’d play. After hours of sectionals, the saxophones returned to rehearsal, nailed that unison line and sounded like one huge saxophone.

We would ride ferries together to compete in festivals, wake up at 5 a.m. to make it to the 6:20 a.m. rehearsals and play pranks on each other during our annual trip to Vashon Island for jazz retreat.

Ask any instructor how to play jazz and they’ll say that in order to play jazz, you need to listen to jazz. I have no idea what the first jazz song I heard was. My parents listened to 98.9 FM when it was Seattle’s smooth jazz station nearly every night, and, soon enough, I was listening to this station night and day.

The more I listened, the more I started talking with other people about this music. According to a study in “Psychological Science,” music is the most common conversation topic among people interested in becoming friends. It wasn’t long before we all gushed about the trademark “sheets of sound” playing style of John Coltrane, the masterful arrangements and political statements of Charles Mingus and the genius of Ellington’s compositions. We argued about which song had the better solo from Miles Davis — “So What” or “Freddie Freeloader.” All of my friends have witnessed me go on a 10-minute rave about a jazz musician or album at least once.

This phenomenon is known as homophily, meaning “love of the same.”

“There is this intrinsic need to affiliate and associate with people who are like-minded,” says Joseph Trimble, a professor of psychology at Western. “It boils down to choice of partners, lovers, spouses and clubs.”

Music taste can also reflect your personality. According to a 2007 study in “Psychology of Music,” people who prefer complex genres like jazz and classical music tend to be more open to experiences when compared to someone who likes pop or country music. So maybe one reason I seek out people who like jazz is because we could have similar personalities.

But by the end of high school, I wondered how or if I could find similar friendships at Western. I didn’t want to major in music, but I couldn’t leave jazz behind.

I auditioned for Western’s jazz program by playing Miles Davis’ “All Blues,” one of my favorite songs from the album “Kind of Blue.” To my disbelief, I made it into the Western Jazz Orchestra, known as the top big band in the program.

It was difficult for me to move past the mixture of admiration and fear I felt toward the other band members who were well into their music education or performance majors. It took a few weeks, but soon the ice broke and I befriended the lead trumpet player, Nick Wees.

He’s played in many different ensembles and seen how communication and connections between musicians is crucial in smaller groups. Without that connection, musicians may feel less comfortable taking risks while playing.

“In a small group setting, it’s more about free expression,” Nick says. “The conversations between musicians verbally, and musically, can go a lot more places.”

For Nick, music is the key shared interest he looks for when getting to know someone. A lot of the connections he’s made in music have come from being around the same group in classes and rehearsals in school.

“There have definitely been a few people in my life who I initially tried to approach because I really liked their playing,” Nick says.

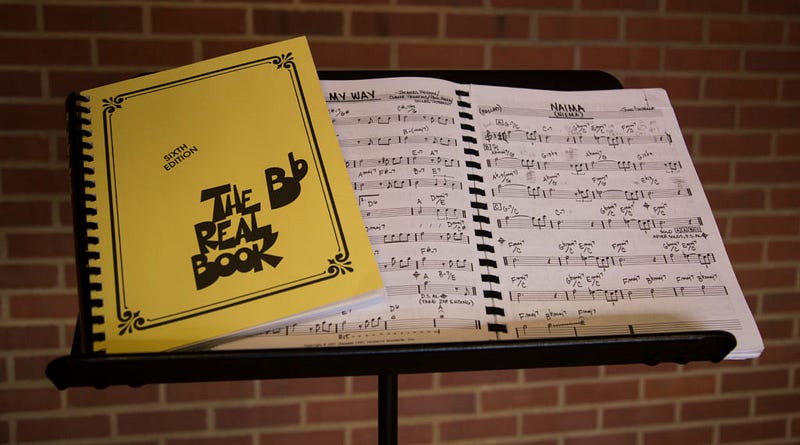

Because I wasn’t a music major, I found it difficult to completely fit into this group outside of the times I had a “Real Book” in hand or my saxophone hanging on my neck.

Seeking the camaraderie I experienced as an editor at my high school’s newspaper, I signed up for The Planet, one of Western’s student publications, and learned about podcasting. I fell in love with this storytelling medium and struck up a conversation with the editor Ryan Evans, who taught the podcasting workshops, to learn more about radio.

The conversation quickly shifted to music, since he also worked as the curator of the jazz, funk, soul, blues and other specialty genres in the library of Western’s radio station, KUGS-FM. When he mentioned Charles Mingus, my ears perked up immediately. Frankly, I couldn’t believe this guy even knew who Mingus was. This was the first time I had met someone who liked jazz, but didn’t play it.

We began exchanging music in the form of YouTube links and long lists of recommended artists. Ryan was into the late era of jazz, where fusion and free jazz reign supreme. I had no prior interest in or knowledge of this sub-genre, but soon I was advocating for the screaming saxophones, cosmic references and collective free improvisation of what many call “weird jazz.”

Although this seemed entirely novel to me, it was the social identity theory in action. According to a 2009 study in the “Journal of Adolescence,” individuals in music-based friendships may gain social identity and build self-esteem or feelings of belonging through taking on similar music preferences to that of their friends.

“It’s that communal sense of being understood and being accepted that reinforces one’s struggle with identity, their status in life and their sense of belongingness,” Joseph says. “All human beings have this strong desire to belong.”

Unfortunately, I met both Nick and Ryan in their last couple of quarters at Western. I wasn’t sure these friendships would last. Even though Nick now attends California State University, we still Skype every now and then to jam over the blues. I continue to exchange music with Ryan in the form of Spotify playlists as he teaches English abroad.

Friends tend to feed off one another, sharing bits of personality traits back and forth, according to Joseph.

“There’s this bond that’s established and it’s extraordinarily deep and strong,” he says. “It goes way beyond the 46 percent that’s driven by the DNA.”