Realignment

Chiropractic’s modern schism and its occult history

Story: Bailey Jo Josie

Photos: Archival

A delicate placement of the head to side, as if the patient is asked to look up at the light and appear deep in thought. Firm hands frame the jaw and throat, grab, hold and POP! It’s all over. No, this isn’t a dramatic murder scene from a screenplay or a novel; it’s a typical chiropractic appointment, specifically a neck realignment.

“The health of a joint depends on movement to get nutrients in and waste products out. It’s like a sponge in that it requires active motion to make this happen,” says Dr. Matthew Tellez, a Bellingham-based chiropractor and naturopathic. “It really is an art and a science, though modern chiropractic is about science.”

Chiropractic has been around for over a century and according to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, it is described as “a health care profession that focuses on the relationship between the body’s structure — mainly the spine — and its functioning.” Though the American Chiropractic Association estimates that over 27 million Americans are treated annually by a chiropractor, it is still saturated with controversy.

Despite the high use of chiropractic as a way to deal with pain — mostly in the lower spine — it is generally considered a “complementary health approach” and its origins came from spiritualism, not science, according to the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management.

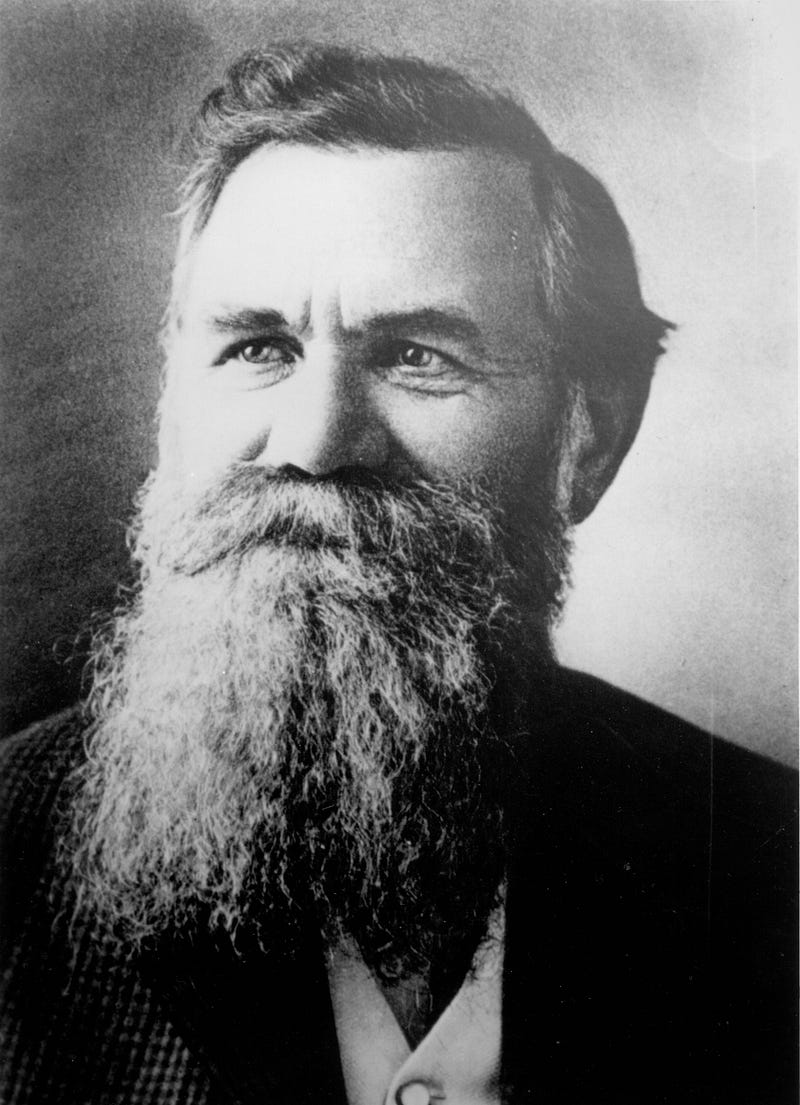

Specifically, it came from a man who went by the name D.D. Palmer — short for Daniel David — who invented chiropractic by using adjustments to supposedly cure a man of his back pain and deafness over a century ago. Surprisingly, the man he claims to have cured corroborated this.

Harvey Lillard was a janitor who lived with hearing loss for close to two decades before he became the first patient of chiropractic. Lillard’s testimony stated, “Dr. Palmer told me that my deafness came from an injury in my spine. This was new to me; but it is a fact that my back was injured at the time I went deaf. Dr. Palmer treated me on the spine; in two treatments I could hear quite well. That was eight months ago. My hearing remains good,” according to the David D. Palmer Health Sciences Library.

This may seem bizarre and completely anecdotal, but it is the complete basis for chiropractic that we know today.

Palmer believed that diseases in the body were caused by the nerve flow being affected by the misalignment of spinal vertebrae. He was a magnetic healer before he created chiropractic, which meant that he would heal patients by increasing circulation in their bodies through magnetism. Palmer’s son, B.J. Palmer, later wrote of his father’s magnetic healing, saying, “[it] consisted of [the] patient lying on couch, back down — he sitting alone-side, with hands resting above and below, in 15-minute periods, flowing HIS magnetism for that period.”

B.J., whose history with his father was tumultuous at best, also became a chiropractor and helped further establish the Palmer School of Chiropractic, a school that’s still in session today.

D.D. and B.J. are main subjects in a book written by Holly Folk, a comparative religion professor at Western. “ I focus on the first several generations of chiropractors and I talk about the way that they build chiropractic theory as a form of ideological cohesion and certain sorts of structural benefits, like it’s easier to license a practice when you have a science to articulate,” Folk says.

Her book, “The Religion of Chiropractic: Populist Healing from the American Heartland,” looks into Palmer’s philosophies, his practices and their metaphysical and occult influences. Though the origins of chiropractic may seem odd, what Palmer wanted to expand is even stranger. In a letter written in 1911, Palmer wrote that chiropractic must be established as a religion.

“I am the fountain head. I am the founder of chiropractic in its science, in its art, in its philosophy and in its religious phase. Now, if chiropractors desire to claim me as their head, their leader, the way is clear. My writings have been gradually steering in that direction until now it is time to assume that we have the same right to as has Christian Scientists,” Palmer wrote.

Regarding Palmer’s letter and the title of her book, Folk made a quick clarification. “Chiropractic is not a religion, although, [it] certainly has spiritual views. And the reason why I call the book “The Religion of Chiropractic” is because around 1910–1912, chiropractors themselves had an argument about whether or not chiropractic should become a religion,” she says.

“Chiropractic is not a religion, although, [it] certainly has spiritual views. And the reason why I call the book “The Religion of Chiropractic” is because around 1910–1912, chiropractors themselves had an argument about whether or not chiropractic should become a religion,” she says.

Palmer was a peculiar man, and in many ways tried to retcon his prior teachings and his own creation. In the same letter, he insisted that what brought him the knowledge of chiropractic was a spirit from “the other world” — specifically, the ghost of a medical doctor.

“So, my hunch is that none of that happened,” Folk laughed. “My guess is this — D.D. says at the beginning of ‘The Chiropractor’s Adjuster’ that he hadn’t told people this before, but now he is prepared to own up to the fact that he learned chiropractic secrets from the ghost of a dead doctor named Jim Atkinson.”

Folk says the theory for why Palmer would make such an outrageous claim may come from the social circles he was involved in.

Palmer was friends with a man named William Juvenal Colville, who was a “popularizer of metaphysical and esoteric ideas.” Colville wrote many books about spiritualism and his ideas left such an impression on Palmer that his 1910 book, “The Chiropractor’s Adjuster,” was dedicated to Colville.

Folk says by alluding to a dream intervention by the ghost of a doctor, Palmer was making an obscure reference to Egypt, Rosicrucian history and other metaphysical lore. Palmer was essentially making himself out to be a great thinker in an age of great metaphysical thinkers.

“I don’t think he learned it from a dream but I think this was his sort of nudge of saying ‘I have established myself in this esoteric circle,’” Folk added.

That’s a lot of information to take in. Which is also part of why Palmer’s insistence on creating a religion out of chiropractic never took off — his students and other chiropractors were just not interested in it and the idea of turning chiropractic into a religion was abandoned.

So chiropractic came from spiritualism and esoteric philosophy — where does the science come in? Studies looking at whether or not there is sound science in chiropractic have been found to be inconclusive in regards to claims that it heals a certain ailment or illness, outside of lower back pain. This is due in part to the fact that a large part of chiropractic relies on spinal manipulation.

Spinal manipulation is what chiropractors do to get that distinctive “pop” from a patient’s joints; by using different techniques that involves twisting, grasping, pushing and pulling of the body, the practitioner is able to manipulate the vertebrae and relieve any pain or pressure in the patient.

Research conducted by three chiropractors and a doctor of physical education looked at the spiritual aspects of chiropractic and concluded that there is little evidence to back it up, according to the journal.

In the article, one writer reasons, “When chiropractors use spinal manipulation therapy for symptomatic relief of mechanical low back pain, they are employing an evidence-based method also used by physical therapists, doctors of osteopathy and others. When they do ‘chiropractic adjustments’ to correct a ‘subluxation’ for other conditions, especially for non-musculoskeletal conditions or ‘health maintenance,’ they are employing a non-scientific belief system that is no longer viable.”

This science goes against what Palmer believed in and what his school is based entirely on, so what do these results mean for the practice itself? It has caused a schism within the practice of chiropractic. Those who still cling to Palmer’s ideals that vertebral subluxation causes most diseases are called “straights”, while “mixers” want to move toward more science-based medicine.

Dr. Tellez sees himself as a mixer, but also more than that.

“My practice functions like primary care but without the pharmaceuticals,” Dr. Tellez says. In other words, his field of chiropractic is eclectic and observant, though still outside the realm of what one would expect from a regular doctor’s visit.

He doesn’t prescribe drugs but will offer more natural alternatives, like vitamins. Tellez says he believes that the human body “is a living miracle with supreme sophistication that even the most educated medical mind will never fully understand or comprehend.”

Dr. Tellez’s form of alternative medicine has increasingly become the norm within the chiropractic community, possibly because of studies that show little evidence toward Palmer’s original theories. Fewer and fewer chiropractors consider themselves “straights,” but according to Folk, this is a fairly recent trend.

“It’s kind of funny because, the majority of chiropractors are considered mixers although, until almost 1980, the majority of chiropractors graduated from Palmer College, a ‘straight’ school. I would say that until you get to the most recent generation of chiropractors, the typical chiropractor was going to be a straight college graduate who was doing a certain amount of mixer practice,” Folk says.

So the division within chiropractic isn’t as wide as one may think? Well, yes and no. As Paul Ingraham, a writer for Pain Science says, “The goal of chiropractic is to help people with musculoskeletal pain and injury, and that problem can of course be approached in a scientific way, and many chiropractors have been doing it for a long time already.”

The only real question is whether the idea of a “chiropractor” will survive the process. And that’s up to chiropractors, I think. They may succeed in maintaining their identity, or they may lose it, depending on how hard they cling to their origins.

Palmer’s legacy is still in the practice of chiropractic, but time will tell whether or not his ideals and theories will be fully abandoned. However, it may never disappear as long as there is a patient in a chiropractic office, rubbing their neck after an adjustment, deciding in their own mind whether or not the sharp POP! will alleviate any discomfort in their joints.

As long as these people find comfort from chiropractic for their pain, Palmer’s gift will never die. Just don’t count on it to cure your deafness.