Black Tar Heron

A Skagit County industrial zone is home to one of the West Coast’s largest heron nesting colonies

Story and photos by Jesse Nichols

A shriek cuts above the background noise of saws and passing trucks on South March Point Road. It sounds like a velociraptor from the 1993 film “Jurassic Park.” It’s coming from a 3.5-acre patch of woods above a steel fabrication shop, which is home to one of the largest heron colonies on the West Coast.

March Point is an industrial area outside Anacortes, home to oil refineries and heavy industry.

“The herons are great neighbors. They just do their thing and we do our thing,” says Justin Rawls, the director of operations at the construction company T Bailey, which neighbors the heronry. The herons have nested on March Point as long as Rawls can remember.

The first written documentation of the heron dates back to the 1950s when the refineries were built, says Molly Doran, executive director of Skagit Land Trust, the organization that owns part of the heronry property. March Point used to be a boggy forest, Doran says, and the heron colony could’ve existed long before they were first recorded.

There are a lot of theories on how the herons chose their home. March Point is isolated — apart from trucks and trains, the area gets little traffic. The herons share the woods with a local eagle, which prey on heron eggs and chicks. But in exchange, the herons get protection.

“If you don’t have a resident eagle, other eagles can come in and prey,” Doran says.

Above all that is the leading theory: Food. Padilla Bay, a long, shallow bay filled with eelgrass, shellfish and small fish, is just across the street from the nesting site. Two other bays — Fidalgo Bay and Similk Bay — lie about a mile to the south and the west. Every spring, the herons move into their home in the woods and spend the season flying food and twigs from the bay to their nests. In 2016, Skagit Land Trust counted 497 nests on the part of the property they own.

The land trust installed a solar-powered video camera in a tree overlooking the nests in 2006. During the nesting season, the camera — dubbed the heron cam — broadcasts its video to the Padilla Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve across the bay. Volunteers at the reserve study the herons video stream to track the size of the colony and the number of chicks that survive the season.

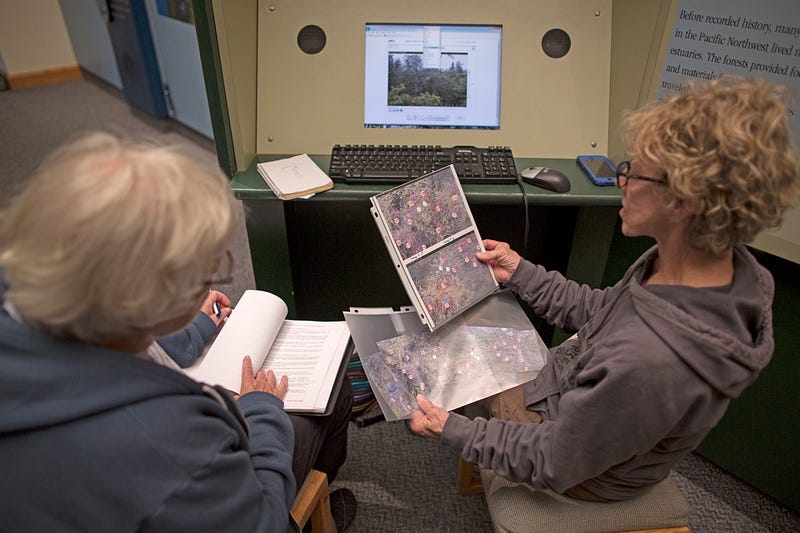

Gerri Gunn and Pat Steffani have been volunteering weekly at the heron cam since mid-spring of 2017. Before they were volunteers, Steffani was a computer programmer and Gunn was a nurse. This is one of their first times doing environmental work.

“I’m sure people are using this to see the effects of climate change and pollution,” Gunn says.

“It’s a baseline in case something really bad happened,” Steffani says.

Gunn can pan and zoom the camera from her computer, peering into each nest as Steffanni takes notes. Suddenly, Gunn swings the camera to a heron that landed in a nest with two light blue golf ball-sized eggs.

“Oh boy!” Steffani says.

Gunn identifies the nest as number 14.

“Oh, we’ve been waiting for 14!” Steffani says.

The nesting season passes quick. Every summer, the herons and fledglings leave their nests to forage around the Salish Sea for the rest of the year. The heron cam shuts down and the volunteers go home. But every spring, the construction workers are once again greeted by the sounds of those familiar prehistoric shrieks.