The Memories That Make Western Washington University

A look into what makes Western the school it is today

Story by JORDAN CARLSON | Illustrations by JILLY GRECO

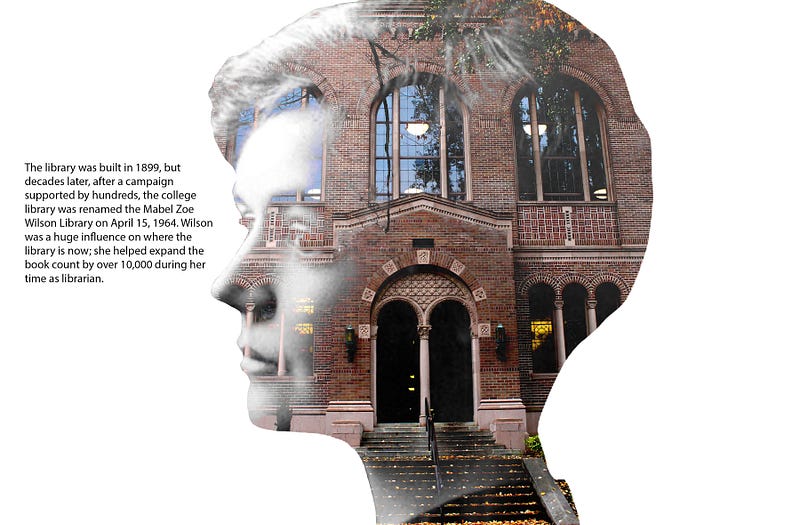

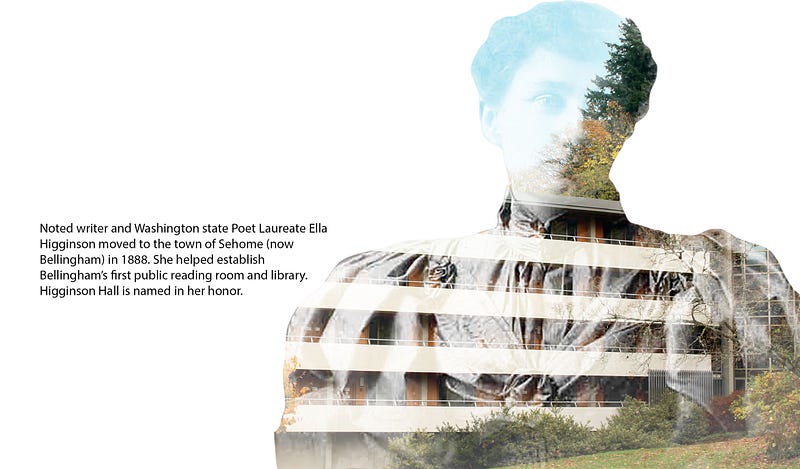

Atop an old peat bog on the side of Sehome Hill, a freshly constructed building known today as Old Main stands three stories high, welcoming the breeze rolling off Bellingham Bay.

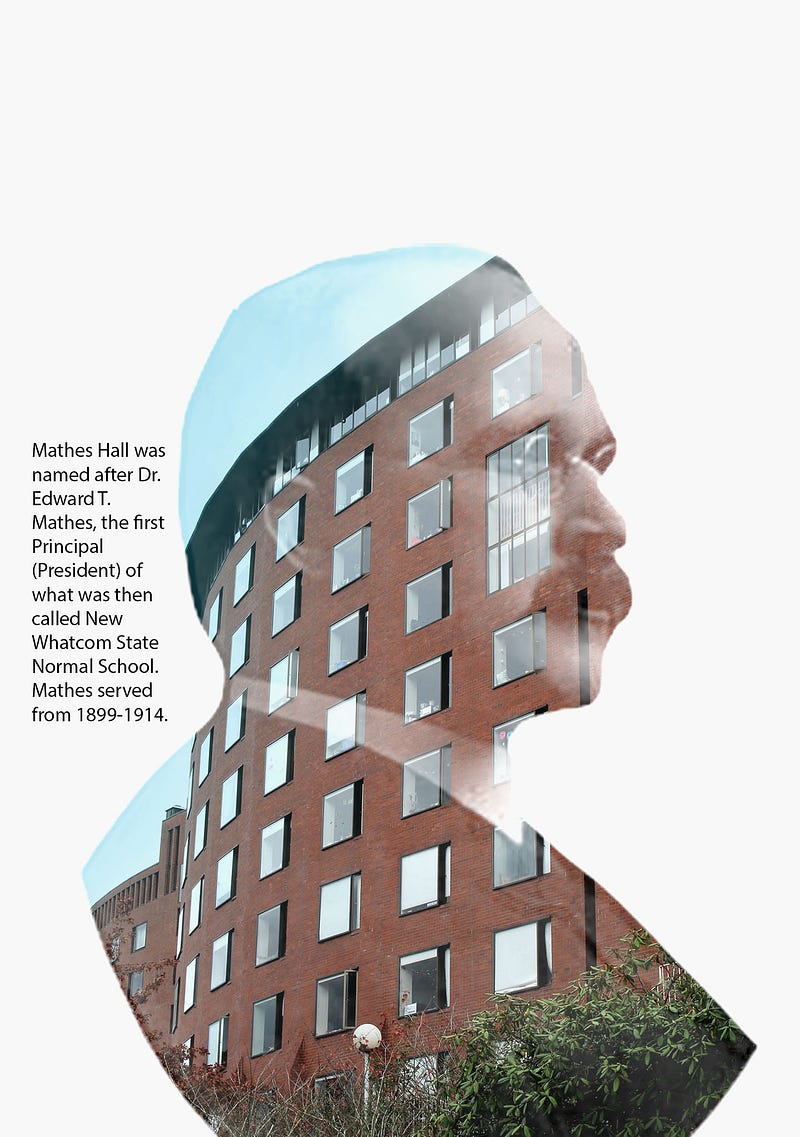

It’s fall, and Old Main — then a school for training teachers called the State Normal School at Whatcom — opens its doors to students. Edward T. Mathes is principal of the 88 students enrolled on the first day of class, Sept. 6, 1899.

Over 100 years later, this one-building school has expanded to more than 60 buildings spanning 215 acres of land. Nearly 16,000 students attend what is now Western, the third-largest public university in Washington state.

The Growth of a Beautiful Campus

Establishing a college in the wet, marshy lands surrounding Sehome Hill proved to be a challenge.

Before officially opening in 1899, plans for a normal school in Whatcom County carried out over the course of 13 years, starting in 1886. One of the major challenges in these earlier years was getting state support and funding for the school.

Washington had recently been founded as a state when three colleges sprung up in the early 1890s in Cheney, Ellensburg and Pullman. The state was hesitant to make a third teacher-training institution in the “remote” town of New Whatcom, and receiving funds for the school proved futile until 1899 when the state Legislature appropriated $35,500 for the maintenance of the school for two years.

The view of Bellingham Bay and forested shoreline, even the soggy land showed promise enough to build a university. Much of Western’s campus is built on top of partially decomposed organic debris filling an old dried-up lake. Many of the buildings are constructed on or around Chuckanut sandstone.

Tamara Belts, special collections manager at Western, works to catalogue and digitize materials pertaining to Western’s campus history. Belts knows much about Western’s history and the struggle to expand a university around rock and unsettled ground.

Belts recalls a lot of difficulty connecting Wilson Library to Haggard Hall with parts of the main library built around Chuckanut sandstone. Before the skybridge went in, connecting the two buildings, a large slab of sandstone was hidden beneath the library.

“They started excavating to put in the skybridge and make that walkway underneath. They were thinking about blasting [the sandstone] out but they decided it would be way too much to do so it ended up being kind of a decorative piece,” Belts said.

As is the case with much of Western’s architectural style, Bellingham’s natural landscape is very much incorporated into the campus aesthetic.

Many of the buildings on Western’s campus had to accommodate the hilly, forested area such as the Viking Union on the hill facing the bay or the Ridgeway Dorms stacked among the tree-laden hillside.

The Ridgeway Project brought accolades to Western, according to Lynne Masland and Linda Smiens, authors of “Perspectives on Excellence,” a campus architectural history. The dorms were recognized as an outstanding achievement resulting in an award, presented by then U.S. Vice President Hubert Humphrey in 1966.

The architectural design for both the Viking Union and Ridgeway Dorms can be attributed to Fred Bassetti, who also took part in the creation of Carver Gym (1959), the Associated Students Bookstore (1960), Fraser Hall (1962) and the southern side of Wilson Library (1962).

Barney Goltz, director of campus planning, contributed much to the beauty of Western’s campus in the ’60s when he took on the task of planning the construction of a new student union building.

University archivist, Tony Kurtz, said the campus planning office was intended to match campus development to academic needs.

“In the ’60s, there needed to be a building boom to prepare for the baby-boom generation, and part of Goltz’s job was making sure the university evolved and along the way, the campus was completed to look a certain way,” he said.

Goltz’s plans for Western included public art throughout campus, nonuniform buildings, cluster college facilities and a campus in which students could walk to any class within 10 minutes. The only downside to his plan was the underestimation of parking space — a problem that still exists today.

“Western people should never forget Barney Goltz, for he more than anyone else is responsible for the beauty of this campus,” former Western President Jerry Flora wrote in his book, “Normal College Knowledge.”

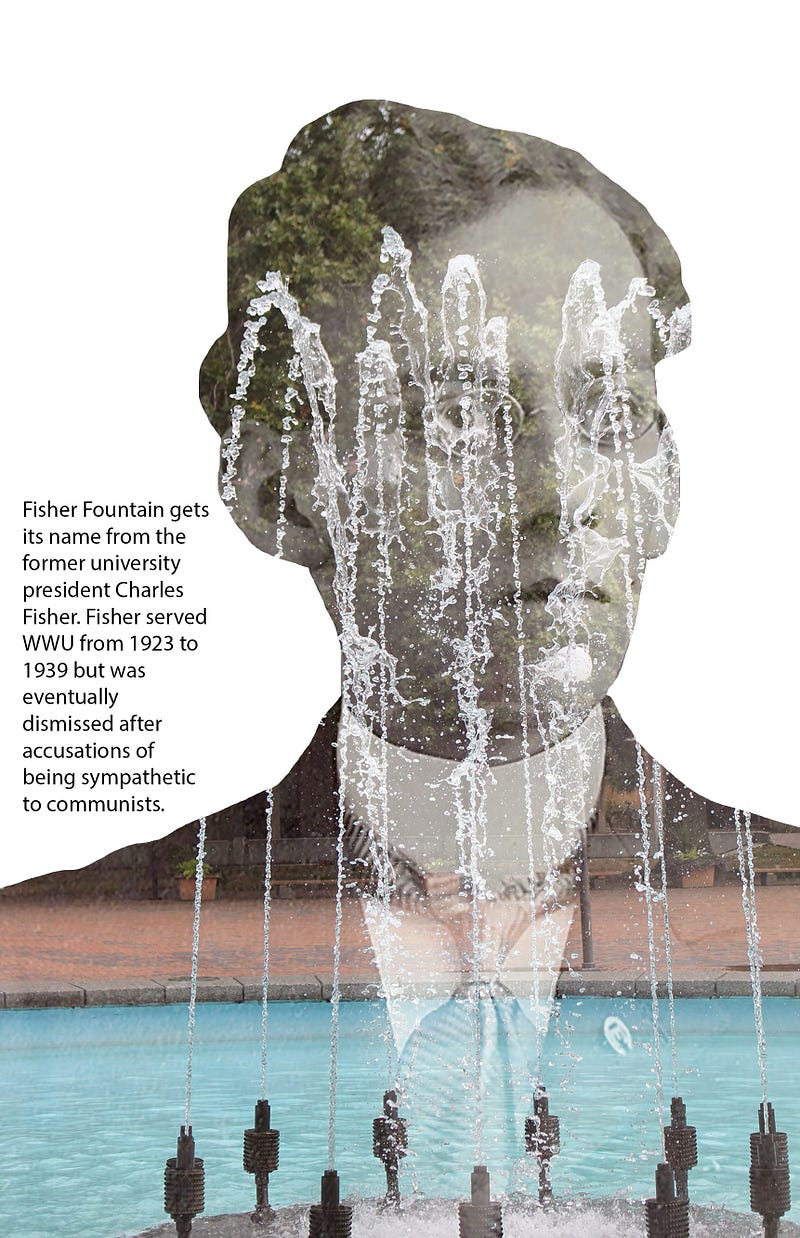

Charles H. Fisher (1923–1939)

Charles Fisher was president at Western during tumultuous times, ultimately terminated by the board of trustees after being falsely accused of being a communist sympathizer due to his educational progressivism in a more politically conservative community.

Western professor and Seattle Times columnist Ron Judd wrote his master’s thesis on Fisher’s termination, titled “The Liberal Arts on Trial: Charles H. Fisher and Red-Scare Politics at Western Washington College of Education.” He was intrigued to find out little research had been done to gather the murky details surrounding Fisher’s dismissal.

With his presidency falling during the years of the Great Depression, Fisher’s liberal ideas were rejected by many, most notably the editor of The Bellingham Herald at the time, Frank Sefrit.

At the time, the Roosevelt administration was in the process of enacting the New Deal, a series of federal programs, financial reforms and regulations aimed at relieving the unemployed and recovering the economy during the Great Depression. The New Deal created a political realignment in America with the majority of Democrats supporting it and Republicans viewing the plan as a threat to business and growth.

“It was a very arch-conservative community here at the time in the 1930s, and Frank Sefrit was kind of emblematic of that,” Judd said. “They were very anti-union, very anti-New Deal, which was considered extremely radical at the time. The conservative people here were very agitated about that, plus they had all been thrown out of power for the first time in their lives.”

Judd said Sefrit was honest about his politics and genuine in his dislike for progressive politics and to some degree public education. But also, he just didn’t like Fisher.

“Fisher was one of the few people in this town who could look him in the eye and basically say, ‘Screw you, I’m not going to do what you want me to do, you don’t have control over me, you don’t have power over me’ and Sefrit took that incredibly personally,” Judd said.

While Fisher was exonerated by the board of trustees in 1935, he was ultimately dismissed by Governor Clarence Martin in 1939 for being a communist sympathizer and fostering anti-American “Red” academics. Judd’s research found the reasons behind his termination could have also involved a financial scandal — an embarrassment to the university during an era in which money was very tight.

Judd describes the scandal as being more of sloppy bookkeeping where money was unaccounted for despite being paid back. Still, his research doesn’t answer why the board of trustees outed Fisher instead of taking the fall, though he does have a theory.

“[The board of trustees] could have just resigned and said, ‘No, we’re not going to fire Fisher, you’re going to have to fire us and take us off the board,’ but they didn’t,” Judd said. “It would have been incredibly embarrassing for them if the governor came out and said, ‘This state-run institution played fast and loose with this much money and these trustees signed off on it.’”

Still, investigations of the firing were described as an infringement on academic freedom by Gov. Martin during a time of social and political animosity.

Judd believes the university should do something to correct the record and honor Fisher’s name in some way other than the ironic Fisher Fountain in the middle of Red Square, symbolic of Fisher’s fight with Western’s own Red Scare.

“Especially in this era where we’re going back and looking at a lot of sins of the past, this is a black mark on the history of Western and Washington state. It’s an egregious example of politics directly interfering with public education.”

Despite the controversy surrounding his termination, there were notable events and achievements during his 16-year administration.

Presiding over a time of student enrollment decline due to the Depression, Fisher was successful in getting funds for a new campus expansion plan, as well as for a new campus library built in 1928 and a physical education building in 1939. For three years, Fisher helped secure the Carnegie Corporation grant to expand the library.

The summer Fisher was terminated in 1939 happened to be the summer the avalanche at Mount Baker took the lives of six Western students during a summer program hiking trip.

Fisher was involved in recovering the bodies of these students, despite being pushed out of office. Now, there stands a monument at the north end of Old Main with the words, “You will be forever climbing upward now.”

The controversy surrounding his termination ruined his career. Fisher’s name was smeared with a communist label.

“He was blackballed from education and he spent the last 30 years of his life regretting what happened here and I think it needs to be corrected, the historical record needs to be corrected,” Judd said.

William Haggard (1939–1959)

William Haggard was president of Western for 20 years, the longest tenure of any president, leaving only for mandatory retirement, according to Flora.

Flora described Haggard as a man of steely control, power and endurance — as such a president was needed following the termination of President Fisher.

“The board wanted constancy and they got it,” Flora wrote. “Any ultraliberal, pinkish hue was cleansed from the campus during those 20 years. No other president has come close to Haggard’s durability.”

During his tenure, several campus buildings were established: The Campus Elementary School — now Miller Hall — built in 1942, the Industrial Arts Building built in 1949, the Auditorium built in 1951, Edens Hall North built in 1955, Highland Hall in 1956 and the Student Union Building in 1959. Haggard was also responsible for acquiring land for future development.

Haggard was somewhat of a stickler, making it clear that faculty should never smoke in the classroom (of course, this was during a time when smoking inside was very common), and is known for telling people to not walk on the grass in front of Old Main.

Haggard designated a faculty smoking room in the south wing of Old Main above what was the gymnasium, now the Old Main Theater. This was the only place on campus where faculty could smoke.

Flora said the room became politically important to the university and vital to its history as it was the only place where faculty came together on a regular basis to talk, gripe and advocate solutions to campus problems.

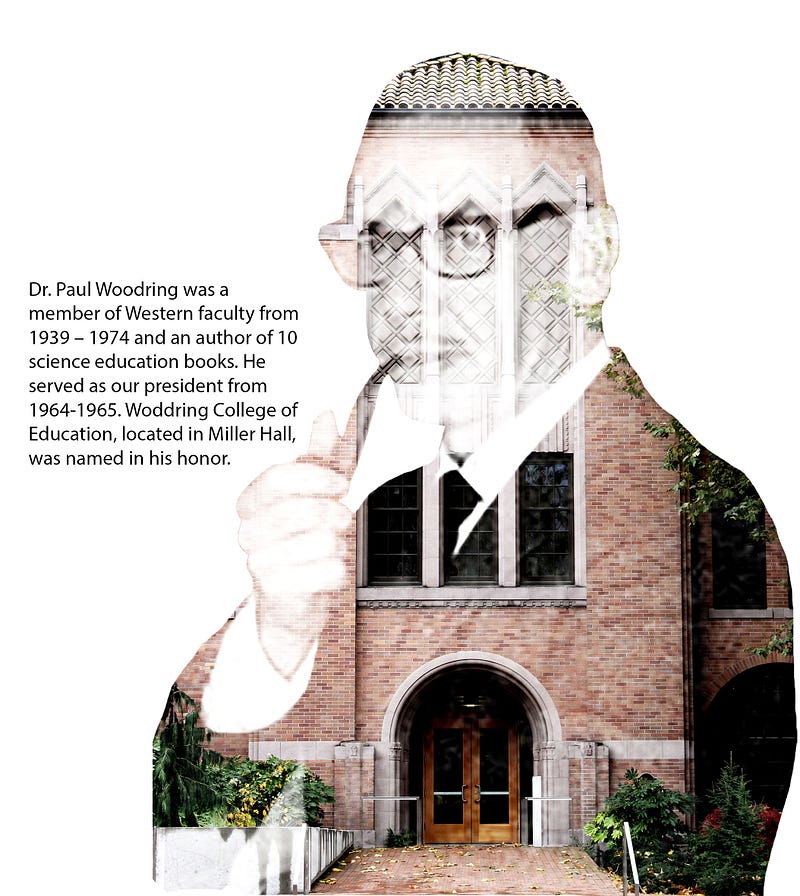

“In that murky room I first heard Paul Woodring discuss a cluster college which eventually became Fairhaven, Don Blood describe our future in computer science and Herb Taylor talk about revisions in the Bureau of Research which lead to the Bureau for Faculty Research,” Flora said.

Many of the ideas brought up in the smoking room were eventually implemented, Flora said. Even carrying into James Jarrett’s administration, the regulars of the smoking room were the primary political force on campus.

Nowadays, regular smokers sit outside rain or shine, the smoking room a memory buried somewhere deep in the walls of Old Main.

James L. Jarrett (1959–1964)

The day President Jarrett assumed office was the day faculty could smoke anywhere they wanted on campus, Flora said.

“Never was there a greater contrast in administrative styles and academic focus than between Jarrett and his predecessor,” he wrote.

Jarrett’s relaxed rules having to do with smoking and alcohol consumption for faculty, administrators and staff, and was known for the parties he would have at his residence.

Flora describes the parties as long, loud and a place where large quantities of alcohol were consumed.

“They were invigorating affairs and for most of us titillating because we were yet under the aura of a more sedate time. All who attended were young, they had to be. A person of my current age could not have survived one of those parties,” he said.

Those who became close to Jarrett would attend his parties regularly, outsiders would come to call this clique “The Ratpack,” Flora said. The Ratpack became an influential group on campus, often generating notions for campus policy — which outsiders viewed as having a chilling effect on the collegiate process.

Despite this, Jarrett was well-known for increasing emphasis on high academic achievement, eventually creating the honors program in 1960. He is credited with creating a strong humanities program also established in 1960, as well as restructuring and creating new departments and programs across campus.

It was during Jarrett’s tenure that there was tremendous growth in student enrollment, faculty and physical growth of the campus. He was responsible for hiring 60 percent of the faculty who remained at Western when he left in 1964, and oversaw the building of the Viking Commons in 1961, the first two phases of the Ridgeway dorms in 1962 and 1963, as well as the Humanities Building in 1963.

Flora credits Jarrett with starting the trend of Western’s outdoor art sculptures, a huge part of what gives Western its charisma.

Rain Forest fountain, which now stands outside the Student Recreation Center, is the first and oldest piece of outdoor art at Western, brought to Western’s campus by former President Jarrett.

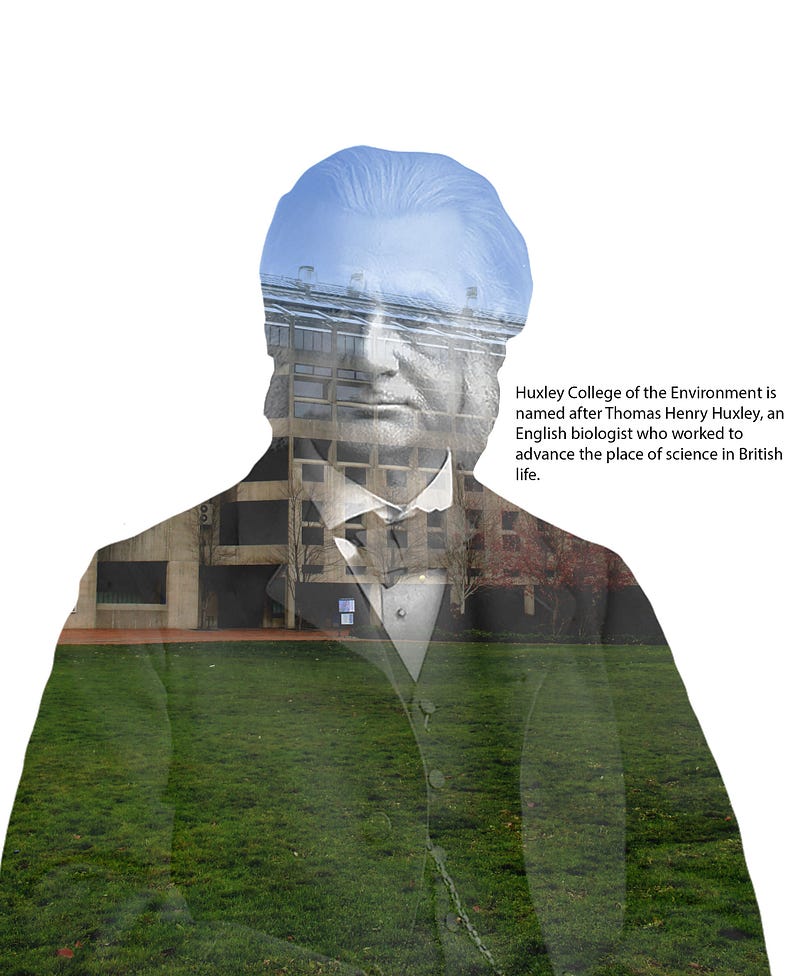

Charles J. (Jerry) Flora (1967–1975)

Flora was a faculty member for 10 years, starting as an assistant professor of biology and the first Western president to be a faculty member before and after serving presidency.

It was during his term that Fairhaven College and Huxley College of Environmental Science was founded to continue Goltz’s plan for cluster colleges at Western, as well as the College of Business and Economics and the College of Fine and Performing Arts. It was also during his time as president that Western’s enrollment increased by nearly 4,000 students, exceeding 10,000 for the first time in history.

Like Fisher, Flora presided over Western during a contentious time in history — the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights era.

Western’s campus showed its political activity and unrest as was common across U.S. college campuses. Western saw 14 campus protests between 1969 and 1970, rallying against issues such as anti-hitchhiking laws, the Vietnam War, the Kent State shooting and ethnic diversity. Western even saw its longest lasting sit-in in Edens Hall where students protested the Vietnam War for approximately a week.

“Please know that during the next few years there were many demonstrations, bomb threats, sit-ins, etc. It was a trying time for a lot of people. Various episodes saw me in trouble with one group or another,” Flora said. “For the first few years, I angered only one faction at a time with enough space between for recovery before the next incident.”

In the eight years of Flora’s presidency, he notes that some disliked him intensely, recalling a defacing of the sculpture, The Man Who Used to Hunt Cougars for Bounty, on the morning of spring commencement: “My eyes drifted lovingly over the knoll to the library and there in great, crude, dripping red letters on the bloated body of the cougar it said “FUCK FLORA!”

Flora had the responsibility of guiding Western’s campus community through the chaos, in which he avoided any outbreaks of violence as experienced by some other universities.

Flora served as the director of the Aquatic Studies Program from 1976 to 1983, including the Institute for Freshwater Studies and the Sundquist Marine Laboratory at Shannon Point. He returned to Western as a professor of biology in 1983 and retired in 1991.

After passing away in 2013, Western’s board of trustees renamed a building at Western’s Shannon Point Marine Center in Anacortes in Flora’s honor.

Where Are We Now?

In the years following, Western experienced the tragic death of President G. Robert Ross in a plane crash north of the Bellingham International Airport in 1987, saw the 15-year administration of its first female president, Karen W. Morse appointed in 1993, and celebrated 100 years of existence at its 1999 Centennial.

Now, Western’s memories are kept alive and preserved in Haggard Hall’s Special Collections and Goltz-Murray Archives Building. Archivists such as Belts and Kurtz help guide the research for projects like Judd’s thesis on Charles Fisher, or catalog materials of 100 years of scholarly achievement for feats like Western’s Centennial Project.

“In order to do a good job as an archivist, you have to know about the context of the research,” Kurtz said. “I have to have a good, solid grounding of the history because when you’re working with the materials, you have to decide the value of those records.”

To Flora, it is irresponsible of a university to remove its memories.

“Destroying all the original buildings and replacing them with new, fancy, rectangular, energy efficient dominoes removes old memories,” he wrote.

While the intimate memories of Western graduates are sealed and forgotten in time capsules beneath the marble slabs of Memory Walk, the years of student and faculty achievement — the stories that create Western’s rich campus history — are the kinds of memories that make the beautiful college we now call Western.

As former U.S. President Richard Nixon once said to Flora, “Oh President Flora, you must be very proud! That magnificent campus situated on the hill overlooking that lovely bay must surely rank among the most beautiful colleges in America!”