The Final Stages of Your Life

Why having an advanced directive is important

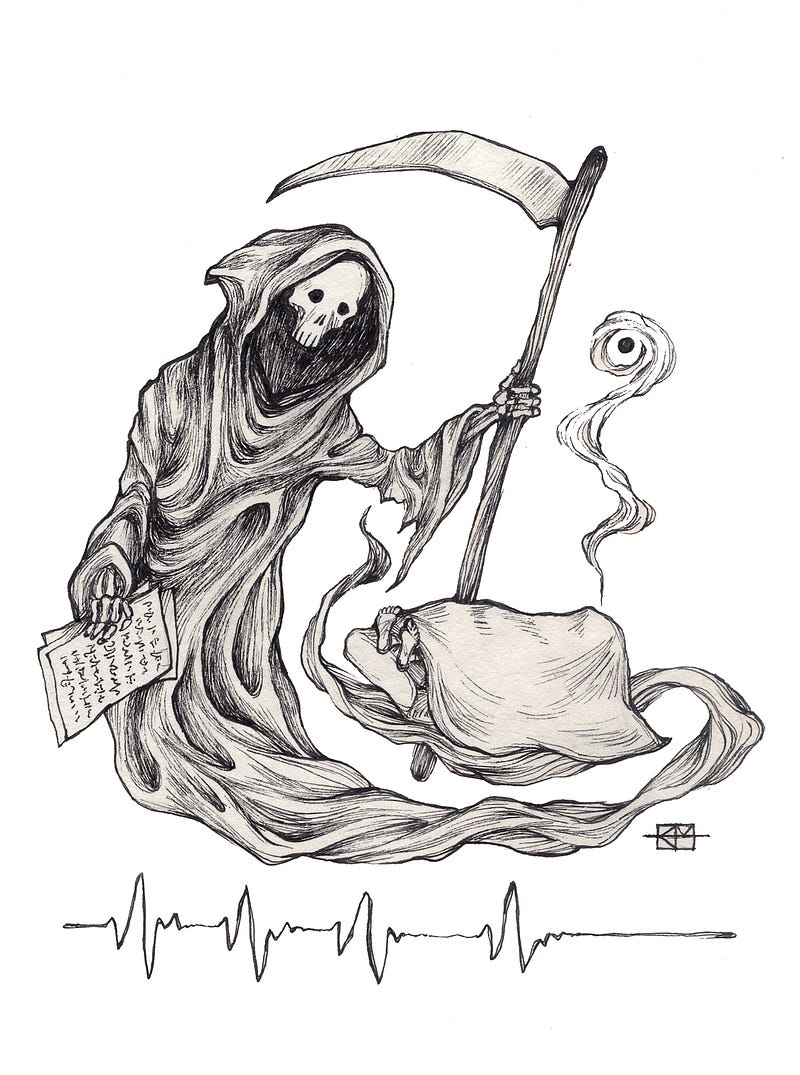

Story by ZACHERY SCHMIDT Illustration by Keara Mulvihill

It doesn’t discriminate. It affects people young and old. It runs on its own time and schedule.

People hesitate to talk about this scary, unpredictable thing until they have a personal experience with it.

It’s in video games and movies but when it comes to thinking about our one’s own death it is something people avoid.

Death visited Dr. Gurpreet Dhillon at the young age of 12, when his mother died and his father was injured in a car crash.

“It was a shocking event. It changed my life forever,” Dhillon said.

Many situations could have happened if Dhillon’s mom survived the car accident. If she was in a vegetative state, the decision on what would happen would be left to Dhillon’s father. If Dhillon’s father was unable to decide because of his injuries, the decision would have fallen on his children because Washington state law.

“Without having direction of what Mom or Dad would have wanted, it would have been a difficult situation,” Dhillon said.

Dhillon believes when predetermined decisions aren’t made, unnecessary tension and stress is created for family members.

“When death comes to your front door and visits your family, it is hard to cope with,” said Marie Eaton, the director of Western’s Palliative Care Institute.

A way to control how a person ends their life is to have an advanced directive. A directive focuses on one’s values, quality of life and beliefs about end of life situations. This legal document allows individuals to specify what health care actions happen when they can no longer speak for themselves.

Dhillon made an advanced directive that reflects his values and gives his family direction on what to do at the end of his life. He is one of only 33 percent of Americans who made an advanced directive, according to U.S. News & World Report.

“Americans don’t plan for their life very well. You plan for your education, your wedding and your career, but when it comes to death people don’t want to go there,” Eaton said.

Australia Cosby, operation manager for the Whatcom Alliance for Health Advancement, finds young people curious about advanced directives, but the subject of death difficult for them to approach.

A solution Eaton has to get young people thinking about death is to require them to make an advanced directive when they get driver’s licenses.

According to the Pew Research Center, 27 percent of people from 18 to 49 thought about to end of life situations occasionally. Americans under the age of 65 made 19 percent of advanced directives, according to Reuters.

Discussing death was a struggle for one of Dhillon’s colleagues until her grandmother’s death.

She looked like something was wrong, so Dhillon asked her what was wrong. At the time, she was caring for her grandmother who had dementia. The woman’s grandmother was in the hospital after complications from a heart procedure. Since the heart procedure, her grandmother’s quality of life rapidly decreased. Like many Americans, she had never asked her grandmother about quality of life or whether she wanted to have the surgery. Regret overcame the woman when she talked to Dhillon about the situation.

The experience she had is something that happens to many people. Dhillon often sees this situation happen in the emergency room where a crisis occurs and everyone in the family has a different opinion on what to do.

“Our society and culture makes us believe we are invincible and can do anything, but really life is so delicate,” Dhillon said.

The biggest cost of talking about death is the time it takes to have a good conversation, Eaton said.

Sometimes, patients and health care providers have different ways to think about end-of-life situations. Eaton believes the medical profession approaches the topic of death upside down because its first prevention is to keep them alive at all costs.

This complex relationship between patient and doctor presented itself one day at the hospital.

A nurse received a startling call from a woman who had just hit her head. As the woman described what happened, the nurse believed she might have internal bleeding. Upon hearing this, the nurse tried desperately to get the person to go to the emergency room, the clinic or urgent care, but the woman chose not to seek medical attention. The nurse asked Dhillon for help convincing the patient to seek medical help.

Dhillon told the nurse it is the patient’s decision to make. At that moment, the nurse stood shocked over what the doctor told her because she saved lives and helped people throughout her career. To put her at ease, Dhillon told the nurse she helped the patient make her decision.

This situation describes the complex relationship between the patients and doctors regarding end of life scenarios. The medical profession’s culture is to try to save lives. However, patients might not want their lives prolonged.

“It’s challenging because it opens up things not everyone is trying to deal with,” Dhillon said. “We are trying a multipronged approach of how we build more comfort around changing this culture and having these conversations that are so important.

Whatcom County is trying to increase the percentage of people who have signed up for advanced directives. Estimates show around 30 percent of people in Whatcom County have advanced directives, according to The Bellingham Herald.

“It is your wishes as you explain in your own words what quality of life is important when you can’t speak for yourself,” Cosby said.

Washington state has many advanced directive forms but the recommended one to fill out is the Washington State Medical Association form because doctors can readily pull up the form in their systems. The forms talk about wishes, value, treatments, naming power of attorney and quality of life value statement. In Washington state, a witness has to be present or notarized.

“At the end of the day, you get to make the decision,” Dhillon said. “But you get to make one you understand that you are choosing.”