Providing Safe Passage

This a story of the incredible life of Captain Deborah Dempsey, a female master mariner I ran into while hiking. As Dempsey recounts important moments in her life, our experiences hiking together are interwoven throughout the narrative.

Story by MCKENNA CARDWELL | Photos by HARRISON AMELANG, JOHN WUBBEN & JILL JOHNSON

Her arms wrapped around me as I buried my head into her neck. She hugged me close, a protective shield from the panic taking over. I hiccuped and gulped for air as tears flowed from my eyes, dampening her shoulder. There in the woods, I held on to a stranger.

“Hey,” she murmured, her voice deep and comforting. “I’m going to get you out of here.”

The late afternoon sun crept toward the horizon, casting long, blue shadows across the forest floor. When she let go of me, she introduced herself with smiling blue eyes, a worn beanie covering her short silver hair.

“My name is Debbie and this here is Barkley,” she said, pointing to her bounding poodle. “We hike around here nearly every day and it’s easy to get lost. Have you had lunch? Do you need any water?”

Once I could breathe steadily again, I tried to talk, but my words stumbled out of my mouth. Yes, I had water. N-no I hadn’t eaten. I stammered out my story of making the decision to hike alone and straying away from the main trail. Embarrassment burned my cheeks.

Debbie’s strong fingers grasped my hand as she insisted she lead me back down to the trailhead, immediately silencing the voice lurking in the back of my head repeating, ‘stranger danger.’ I would soon discover this woman had a knack for helping people find their way home, a talent she turned into a long and successful profession.

Captain Deborah Dempsey, the trailblazing female mariner, was going to help me find my way home.

We set off. I followed her small frame, stepping in the footprints her boots left as she headed nimbly down the trail. We hiked through the forest, the trees creaking in the wind reminding us of the lack of human voices. Before the silence had a chance to marinate, Dempsey broke it by launching into her story.

The middle of five children, Dempsey was born in 1949 into an active boating community in Essex, near the mouth of the Connecticut River. In 1952, her parents formed Pettipaug Jr. Sailing Academy. When she was old enough, she took the boats out on weekends. Captaining the vessels her family hand-crafted themselves sparked her love of steering ships.

“I grew up so much on the water, that’s just where I’d rather be,” she said, her breath making little clouds in the winter air. “It’s safe to say water has always been a part of my life.”

LISTEN:

[embed]https://soundcloud.com/user-972372344/an-icy-awakening[/embed]

At the University of Vermont, Dempsey majored in chemistry, though by her senior year she wasn’t in love with the idea of making it a career. She divided her time between teaching skiing lessons during the winter and transporting yachts in the warmer months. This continued until a friend of her dads proposed an idea, forever altering the course of her life.

The Maine Maritime Academy, one of only five state maritime academies, was accepting applications. Unfazed by the lack of female students or that no woman had even graduated from a maritime or military academy, Dempsey jumped at the chance and applied.

“I sent the application in, but I changed the male gender pronouns to female,” she said. “I changed ‘he’ to ‘she,’ ‘baseball’ to ‘softball,’ you know, wherever it was appropriate.”

She was accepted and began taking classes fall quarter of 1974. Dempsey credits Title IX, the law passed two years prior, requiring equal funds to be provided to both male and female athletics, as an influencing factor to their decision to admit a female student.

Not that this made it easy for her.

The beginning of her time at the academy included having rocks thrown at her dorm room window, tacks left on her chair and bags of unmentionables left at her door. She was spat on during morning formation and some professors wouldn’t look her in the eye for six months.

The school published false articles about how she started a cheerleading squad, which didn’t help her situation.

“Don’t ever write bogus articles,” she joked, wagging her finger in my direction while stepping over some tree roots on the trail.

I followed behind her, nearly tripping on the same root, and promised I wouldn’t. I wondered how, so far from home and so alone, she continued to find the strength to carry on with her lessons.

“It was just proving yourself every step of the way,” she said. “What made it doable was that I was learning what I really wanted to know. I had found my niche.”

Dempsey graduated in 1976 as valedictorian. At 26 years old, she was the first female to ever graduate from a maritime academy.

“I don’t think you can stop anyone once they’ve found their niche,” she said. “I was like a sponge soaking it all up, I couldn’t learn enough and was enjoying the hell out of it.”

Captain Sandy Bendixen recognizes courageous women like Dempsey for paving the way and mentoring those who follow her. Bendixen also found her niche seafaring and graduated from Maine Maritime Academy in 2005.

“As a sea captain, you have to make more decisions in one afternoon than most do in their entire lifetime,” Bendixen said. “And often those decisions have extreme consequences.”

You can be the best in the business, Bendixen said, but unless you’re able to pass your skills and knowledge onto the next generation, how much have you contributed to the future of the profession?

“Dempsey is incredibly professional and serious, but it’s her true love of the job that really resonates,” Bendixen said. “It’s a nice balance.”

Dempsey and I stopped for a water break, both of us breathing hard. It began to rain and the remaining daylight disappeared behind clouds that loomed above the treetops, leaving a gray haze.

“Shipping comes in waves, literally,” she said, wiping cold sweat off her brow. “It was a down period when I graduated, so there weren’t too many opportunities available, but I went straight to work for Exxon.”

After graduation, Dempsey continued to face pushback for her gender. She recounts a conversation with her captain aboard a carrier for Exxon, who she said begrudgingly accepted her presence aboard his ship.

“I thought I’d never see the day,” he grunted at her.

“What day is that, Captain?” Dempsey asked.

“Women on the bridge, and I can’t do a damn thing about it.”

She worked with Exxon for a year before she left to work for Lykes Bros.

Steamship Co. There she spent 18 years transporting cargo around the world, spending months at a time at sea.

In 1993, one of the ships she captained, the Lyra, had been sold and was in the process of being transported without a crew. A heavy storm broke it from its tow, leaving the dead ship rocking in the waves and drifting closer to shore with thousands of gallons of oil on board. Dempsey received a call from Lykes management asking how soon she could get there.

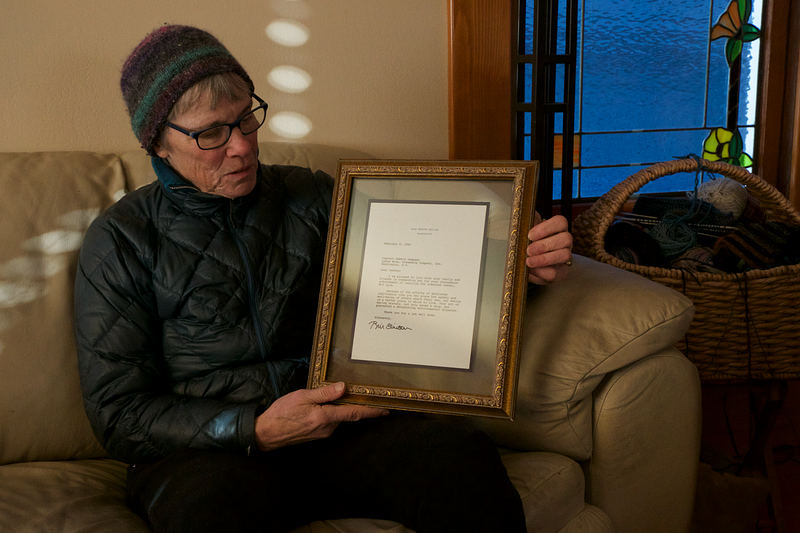

After being helicoptered onto the deck, Dempsey, along with a few others, succeeded in making their way through the mess on board and anchoring the vessel. This rescue mission earned her and the team a thank you letter from former President Bill Clinton, which she keeps framed.

After working for Lykes, Dempsey was recruited to work as a Columbia River Bar pilot in 1994.

To be considered for this job, applicants must hold an unlimited master’s license with at least two years sea time. Altogether, applicants are required to spend 15–18 years total at sea to accrue the necessary amount of experience.

Dempsey hit all the requirements.

Welcoming the challenge, she admitted the career change would allow her to live at home as opposed to spending months at sea. Becoming a pilot would also mean she would be spending most of her time doing what she loved — steering ships.

Following her training, Dempsey began her work on the Columbia River Bar, an area known as “The Graveyard of the Pacific” due to the number of collisions that occur there.

“It was a rude awakening working in extreme weather like that,” Dempsey said. “It’s some of the worst weather you’ve ever seen. I mean 28-foot breakers over the bow of the ship. It’s scary.”

Amid the severe weather conditions, a pilot must be able to navigate ships through the area without looking at any charts. All of the maps are in your head, Dempsey said, pointing to her temple.

Captain Curt Nehring worked with Dempsey as a Columbia River Bar pilot for nearly eight years after Dempsey trained him. Despite 23 years of experience on the sea prior to becoming a pilot, Nehring said this job in particular is so challenging he witnessed captains work only a few weeks before walking away.

“[Dempsey] is one of the best training pilots I’ve ever had,” Nehring said. “She was always under control and knew just how far to let you go before she stepped in.”

Among the treacherous duties of the job, a bar pilot must transfer between the ship they are assigned to navigate and the pilot boat. This is achieved by scaling up and down a ladder which hangs off the side of each ship, while both vessels are rocking in the waves. When pilots are disembarking, they have to climb down from the ship, push off the ladder, release their hold and fall onto the pilot boat which is floating alongside the ship.

This was a particular talent of Dempsey’s, who, according to Nehring, was one of the top two people he ever saw work the ladder. However, after 22 years working as a pilot, she took a plunge into open water that would push her into retirement.

It was just before 2 a.m. in the pitch black air of the Columbia River Bar. Dempsey was gripping onto the ladder hanging off the side of a Greek carrier ship, the Navios Ionian. She had finished directing the ship through the bar and was attempting to disembark onto the pilot vessel to take her to land, all while wearing a knee brace. A split second before she released her white-knuckled hold, the position of the pilot boat shifted and she let go, free-falling into the turbulent water.

Amid 10-foot waves, Dempsey attempted to make her way to the pilot boat, bobbing above the water’s surface due to the float coat she was wearing. The rope designed to pull her aboard the pilot boat had caught in the propeller and shredded, leaving Dempsey clinging to the side.

Her head dipped below the water’s surface as her feet rubbed against the bottom of the pilot boat, leaving remnants of the blue paint on her tightly-laced boots.

Eventually, the crew used a safety basket made for rescuing unconscious pilots to haul her out of the water. She spent 11 minutes in the Columbia River Bar before she was finally lifted out shaken and cold, but otherwise unhurt.

The fall highlighted a personal vulnerability she had been become increasingly aware of — her age was beginning to work against her. It wasn’t long after that Dempsey made the decision to retire from piloting.

Dangerous and challenging, the water is still home to Dempsey, even after she made the tough decision to stop working.

“The phrase ‘can-do attitude’ epitomizes her life,” Nehring said. “She is always looking for the next challenge and there is always one more adventure down the road.”

It didn’t take Dempsey long before she found a new project. In 2007, Dempsey helped found the Community Boating Center in Bellingham, a nonprofit organization teaching community members the skills needed to recreate safely on local waters.

“Being on the water means everything to me,” Dempsey said. “It means challenge. It means peace, solitude, fun. It means learning things beyond what you ever thought you could learn.”

The rain poured down on us, washing away any evidence of tears that rolled down my cheeks an hour ago. We reached the trailhead and the trees opened up, revealing a small parking lot alongside the highway.

Barkley jumped into my car, his dirty paws leaving little prints on the backseat as I drove to where Dempsey parked her red pickup. The car hummed and rain pattered the roof as we found our breath.

Once again, quiet filled the air between us, but this time it was comfortable. We were no longer strangers but friends and the route home was clear. The master mariner guided me through the panic, revealing the path to safety — a skill she continues to carry on both land and sea.