Jane Wong’s Literature of Migration

Story by LINH NGUYEN Photos by HARRISON AMELANG

Poet Jane Wong conquers the journey in challenging the stereotype on almost every first-generation immigrant child.

BELLINGHAM, Wash.- In an English class on Wednesday, Jan. 12, 2018, Jane Wong and her students are welcoming poet Cathy Linh Che and her new book of poems, “Split.” The class plays an ice-breaker game introducing each person’s name and describing their feelings in one word.

“My name’s Jeremy, and my word is — sunshine,” one student sitting in the front row starts the game while Jane’s trying to solve the computer’s technical problem and Cathy Linh Che’s opening her note.

“My name is Austin. Uhm.. and I like the word — wild.”

“Hi! My name is Faye. I have been thinking about the word — journey.”

“My name is Maggie. One word that keeps bouncing in my head is — remembering.”

“I’m Hailey. I want — more.”

“I’m Aaron. And I’m thinking about — coffee.”

“… Elie. And my word is — growth.”

“I’m Matt. The word I have is — better. Because I had food poisoning last night, and it has been better since the morning,” another classmate says.

“I’m Lauren. And I’m thinking about — love.”

“… Jake. And my favorite word is — beeves. If you don’t know, look it up. It’s plural of beef.”

The room cracks up with laughter. The atmosphere is full of humor. Folks are giggling and guffawing with Jake’s word choice.

“I’m Denis. I got in a pre-calculus class last week. So, I’m thinking of — mortality.”

The class bursts out laughing again.

Who would imagine the little quiet girl Jane Wong who was so shy in middle school could become an assistant professor in her early 30s.

. . .

SHREWSBURY, N.J. — Her family has run a Chinese takeout restaurant on the Jersey Shore since Jane was little. The restaurant’s kitchen is where she learned to write. Jane nurtures and embraces her creative writing skills from this place as she grew up. Jane keeps all the sights, sounds and smells of this kitchen in the back of her memory.

One day in 1993, Jane held her favorite book, concentrating on reading word-by-word, white space, then line-by-line. A school official approached and moved her from school to a trailer where people attended English as a second language classes, ESL. The 6-year-old girl looked around the class where only multinational children stayed. The children being brought here learned English as special education and speech therapy.

But in fact, Jane was fluent in speaking and reading English even before being put in this ESL program. Teachers noticed her English skills, but Jane only returned to a normal school program after three years in ESL.

“The funny thing is that I already knew English. I loved books. I read it in English at a very young age… So, I didn’t know why I was there,” Jane says.

Jane could not gather enough confidence to speak for herself. “I didn’t really speak in class [throughout kindergarten and middle school]. I was so shy.” An ESL teacher would make Jane do United States map puzzles and match the pieces while saying, “California, Alaska, New Jersey” out loud almost every day.

Confusion was spreading among other ESL peers in this special class because they didn’t understand the separation, Jane says. Experiencing this in her early school age, Jane saw the trailers as a clear delineation. “You felt you were not normal, like you weren’t accepted,” Jane says. “The ’90s were a different time when people didn’t understand what race, identity and multiculturalism were.”

Jane Wong was born and raised in New Jersey after her parents migrated from China. According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 1980 and 1990 census of population and housing, the Asian population in New Jersey was 270,839. This was 6 percent within the state population in 1990. The Chinese-American population in the state was 54,338.

Perhaps staying in a special program had partly impacted her self-confidence as a kid. The young Jane saw the situation in an unexpectedly humorous way.

“One cool thing about ESL class is that we didn’t have to do anything difficult. It was just doing puzzles, where we skipped math,” she says, laughing.

The racial stereotype within her education existed until her high school years. Many people have an assumption that all Asian-Americans are into mathematics and less interested in art and humanity subjects, Jane says. In high school, she was always put in AP calculus classes even with low achievement in math. Whereas excellent scores in literature were not enough to get her enrolling in honors English classes. Jane then decided to step up and question the arrangements.

The Asian-American poet received her bachelor’s degree in English from Bard College, a master’s degree in poetry at University of Iowa and moved to Seattle to pursue a doctoral degree in English literature at the University of Washington. She is the first generation in her family to go to college.

. . .

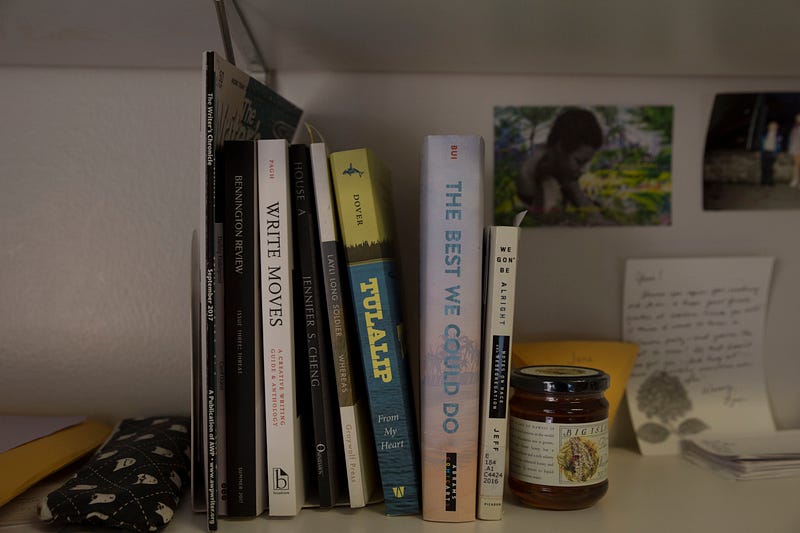

A new chapter in Jane’s career began as she became an assistant professor of creative writing at Western in 2017. She thinks writing, teaching and reading poetry are all cohesive together. “It’s natural to me to teach poetry,” she says.

A former U.S. Fulbright Fellow, Jane chooses poetry as her own way to connect with others. She said poetry is the shortest creative way to get exact ideas across readers’ minds. She honors the language around her and honors the people as well.

Sensory details are ingredients in her art pieces. Language is the plate displaying that art. To Jane, art exists in multiple forms, and literature is one of them. Poetry means the love of language, Jane says. This piece of art is a way to express a different version of the author. She uses poetry to explore and dive into a more intimate and honest part of herself.

“[Jane’s] writing is full of curiosity and play, while it’s still tackling very important political and interpersonal subjects,” Cathy Linh Che says.

Cathy and Jane met at Kundiman Asian American Writing Retreat in 2011. Jane likes to go on adventures, to organize things with family and friends, or go on a hike to look at leaves and mushrooms, Cathy says.

“It’s kind of similar to her poetry. She cares about the natural world and has a curiosity about her mother’s life.”

The two Asian-American poets grew up in immigrant families whereas their parents were working class. “Even our stories’ details were different, we have both experienced some similarity where we watched our parents navigate the world as immigrants,” Cathy says. Writing about families, their lives and children of immigrated families created a bond between the two friends.

Jane’s original major was creative writing with a concentration in fictional writing, since she enjoyed reading novels her entire life. Scenes and character setting is her favorite part. But a story would never be complete without a climax, she says. Jane found herself wandering around and asking, “What should I do with all these characters?”

Jane discovered poetry and changed majors in her senior year of college. She realized, poets do not necessarily have a narrative. They instead create art based on one of the most basic human senses — hearing. Her poems please readers with their sounds and rhythms.

“You can just follow your ears… because words have texture,” Jane says. “Like the word ‘acupuncture’ in itself, is so punctuary with so many syllables.” For Jane, a story is a long process of mapping out structure and nitpicking all the details. While in poetry, she can zoom in and explore within each scene. “That comes more natural to me,” Jane says.

Poems emotionally connect with readers through the ability of providing multidimensional perspectives. Poetry doesn’t spell out the author’s thesis in black and white; it’s about the metaphors, Jane says. This genre of literature allows readers to spend time thinking what message appeals the most to them. “After reading a poem… I wonder how it relates to my life, how do I feel for the writer, and how [the poem] makes readers feel the motions, or emotions through each word,” she says.

The curiosity drives Jane into discovering the idea of ghosts in creative writing. Her doctoral degree final thesis at University of Washington is the poetics of haunting. Jane and Cathy share the same perspective in recreating places and times based on story, trauma and memory. Her first book of poems, “Overpour” refers to a vivid story, in her mother’s voice, with the topic surrounding the ideas of war and child’s play, language and exile, debt, animals and nature. Jane raises questions and brings the possibility for audiences to ask themselves what they know about violence, poverty and alienation.

In winter 2018, Jane taught two courses in the English department. One is the Literature of Migration, English 321, and another is Introduction to Poetry Writing, English 353. Jane achieved a number of awards in literature including 2012 Best New Poets, 2015 Best American Poetry, 2016 Stanley Kunitz Memorial Prize from The American Poetry Review and the most recent, Washington’s 2017 James W. Ray Distinguished Artist Award from Frye Art Museum Consortium and Artist Trust.

The James W. Ray Distinguished Artist Award of $50,000 is the largest cash grant available to Washington state artists and recognizes artists in all disciplines, Artist Trust’s Communications Manager Erika Enomoto said in an email. The nominated art pieces and artists were selected based on the degree of comprehension and skillfulness in art, diversity of background and statewide representation, she says. Competing with 30 other talented artists, Jane received the award in 2017.

According to Erika’s email, Jane’s art piece stood out to the panelists through her expert use of repetition and form as well as storytelling elements. “She’s a talented poet and important voice in the Northwest’s literary community, her work gives voice to stories we rarely hear but sorely need,” Erika said. Artist Trust’s Director Brian McGuigan and Erika express their excitement in Jane receiving the award and are looking forward to working with her through the professional development component of the Distinguished Artist Award.

“To me, poetry is visibility and brings voice,” Jane says. “Know that your voice matters, even in any language, your voice still matters,” she says. “Say it. Say it to your friends. Say it to yourself. Vocalize how you feel. That’s important.”

“I left the light on in the kitchen again.

A spider burned in the bulb. It was a morning

Owl who joined me in the song of its burning.

To raise children with good legs and arms.

Isn’t this all we want? I worry about my daughter.

To be a good man. To be good?

Across the street, a family clears logs from their front yard.

Cedar smoke fills the air. My breath splinters, I hold

a rest note too long. Arrested, always. The sky

Is an ice pattern I could break open. I could

have been a mathematician. I could have loved my daughter.

Saddle up to me, I’d say. Let this horse do the work.

The Good Work — Jane Wong