Voices of Justice

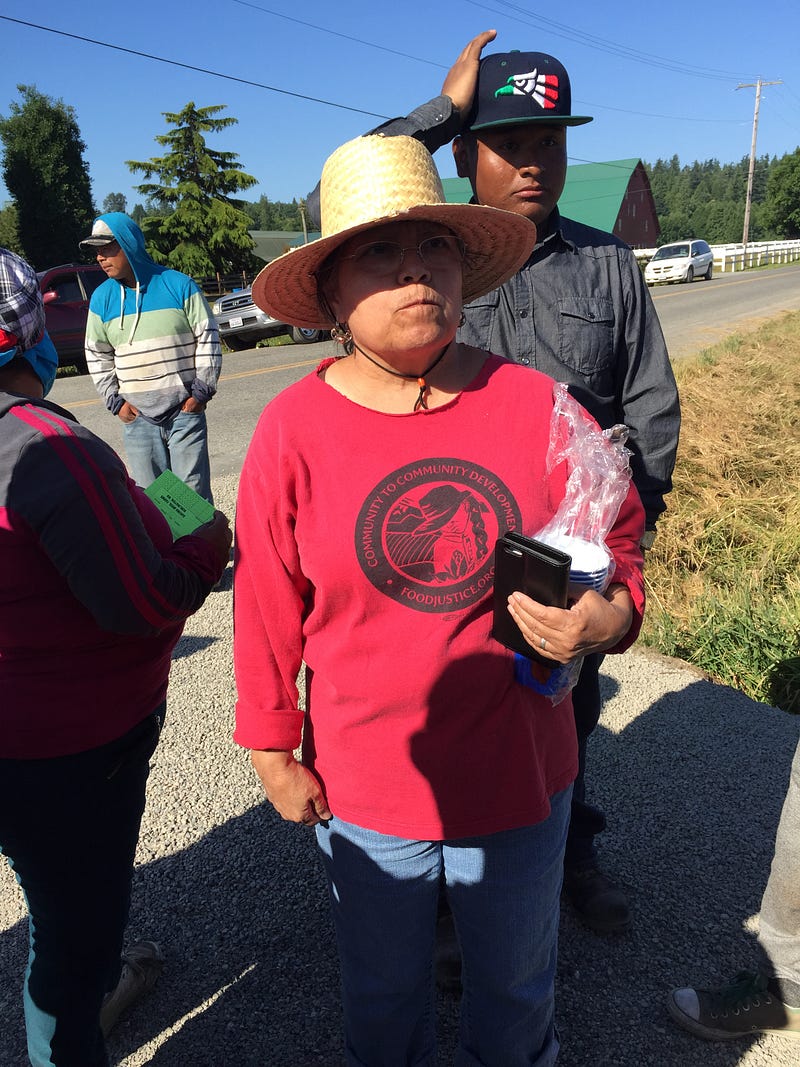

Getting to know the strong-minded individuals that make up Community to Community Development

Story by JACK CARBALLO | Photos by HARRISON AMELANG

In Rosalinda Guillen’s office at Community to Community (C2C) in downtown Bellingham, the walls are festively decorated with traditional Mexican art and literature. These include portraits of civil rights activist Cesar Chavez and original paintings by her father, Jesus Guillen.

One of his paintings is a poster from the early 1990s promoting the Skagit Tulip Festival.

“That was the only poster of the tulip festival that actually shows the farm workers,” Rosalinda said, “and my father painted it.”

C2C is a women-led grassroots nonprofit that takes action toward fighting for food sovereignty and immigrant rights. It has operated in Bellingham since 2003.

Rosalinda is the executive director of C2C, and was born in Haskell, Texas, where her mother, Anita Guillen and Jesus worked on the railroad and picked cotton in the 1950s.

She would only see Jesus for about two months out of the year, as he would travel the migrant circuit across the country following the harvest for work, sending money back to her, her sister and Anita. Jesus had been traveling the migrant circuit with his own family since he was 10 years old and would continue into Rosalinda’s childhood.

Jesus and Anita had saved up enough money to buy property and build a house in Coahuila, Mexico. She noted that life in their concrete house, with a garden and chickens, was a nice childhood.

“I have a really beautiful photo of my father teaching my mother how to shoot rattlesnakes,” Rosalinda said, pausing to think of how she wished she had it with her.

Following the Mexican-American war in 1846, the U.S. government took her grandmother’s land, owned in the family for generations. Politics of this era gave the U.S. government the authority to abuse and displace countless families of minorities from their own homelands.

She recalls what were known as the Texas Rangers committing outrageous acts of violence, racism and displacement against innocent Mexican people and African Americans.

Due to the poverty, racism and exile of that time, Mexican people utilized their skills as farm workers and became the modern-day labor force.

“I believe my father is of that generation that has built the agriculture industry in the U.S.,” Rosalinda said.

Rosalinda and her sister, Elida, were born as U.S. citizens. Jesus was working toward ensuring a citizenship for Anita since he’d seen firsthand the racial injustice toward undocumented people in the U.S.

When Rosalinda was 10 years old, Jesus bought property in La Conner where they would all work in a labor camp at Holbert’s Farms. Here, there were many other Mexican farm worker families who’d come to Holbert’s for work.

Instant connections and community were formed between everybody working on the fields, though tensions were high among the local white community.

There were often acts of racial profiling toward the Mexican farm workers’ families. Rosalinda recalls the constant staring of neighbors who took every opportunity to make complaints or call the police for reasons like music playing or guests entering houses.

Oftentimes, Border Patrol would be called on them to verify their citizenship.

“My father would get so angry, he would stand outside and shout, ‘Whoever did this, fuck you!’ and people would shut their doors,” Rosalinda said. “People made it very clear we weren’t welcome.”

Rosalinda would read various types of revolutionary literature in their house, as her parents were avid readers. Specifically, stories of heroine, activist and writer Pearl Buck, along with books about Fidel Castro and the revolution. It was then she started to piece together that given the social and cultural circumstances they were in, she, her family and all of the farm workers were an oppressed class.

“It left, for me, a very clear understanding of who we were dealing with,” Rosalinda said. “We would talk to our father and say, ‘Do you realize what these people think of brown people?’ and he would reply, ‘It’s been like this all my life, all over the country.’”

When she was 17 years old, she ran off with another farm worker and had her first son. She and her boyfriend at the time joined the migrant circuit themselves. They followed the harvest from La Conner to Southern Idaho, up Eastern Oregon and to Walla Walla, living out of a car.

“Knowing the life makes a difference when you talk to people,” Rosalinda said. “There was no value placed on farm workers, we were pretty much the new slave labor force.”

Rosalinda commented on her fervent disdain for the pity inflicted by white people for being the child of a farm worker.

“We are professional workers like everybody else,” Rosalinda said. “We don’t deserve charity or pity, we want respect and dignity and the wages that are commensurate with the value that we bring to the employer and the industry.”

Rosalinda said there was a refusal on the part of the industry to address farm workers’ value. In her experience, the landowners and farming industry knew they were better than entry-level workers, but were still treated as such.

In 1942, the Bracero Program was a series of executive orders and agreements by the U.S. and Mexico to implement millions of Mexican farm workers on temporary labor contracts in the U.S. According to the Bracero History Archive, it was the largest U.S. labor contract program, and positioned the farm workers against arduous work with low wages from their American employers.

Stemming from concerns about World War II bringing labor shortages, the program would last more than a decade, and was made public law in 1951 during the Korean War. Employers were supposed to only hire braceros in areas of certified domestic labor shortage and not as strikebreakers, which are workers who operate in place of those on strike. Many of these rules were broken and Mexican farm workers suffered harder work and dropping wages while employers benefited from cheap labor.

International initiatives and contracts like these set the stage for modern-day immigration reform and practices, such as the H-2A program. Rosalinda referred to it as “the modern day Bracero Program.”

The H-2A program allows U.S. employers and agencies to bring in foreign nationals to fill temporary agricultural labor jobs, according to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Rosalinda spoke strongly about her distaste for these programs amongst farm workers, and it was common to see them as indentured servitude and legalized slavery.

“It’s a slow death,” Rosalinda said. “The cumulative effects of pesticides on our bodies, the poverty, the lack of education, opportunity and access.”

Rosalinda said at the heart of C2C’s mission, they seek to highlight the industrial and political responsibility that corporations and landowners have to work together to undo this system.

“What this organization tries to do is put the farm worker’s existence and participation in our community as a human rights effort,” Rosalinda said.

C2C is composed of strong believers of this mission statement, including Civic Engagement Coordinator Edgar Franks.

Edgar, a native to Reynosa, Mexico, also joined the migrant circuit with his entire family as a child, following the harvest up the Pacific Coast. When he was 6 years old, his mother found permanent work in Mount Vernon, where he would start working in the fields of Skagit County at 10 years old.

From age 10 until 21, he spent every weekend and summer working in the fields .This included picking cotton, planting seeds, processing grain and operating tractors, forklifts and harvesters.

“It’s still something very personal to me,” Edgar said. “My grandma had her own land in Mexico and grew up in a farming community. She would work the fields in the U.S. to support her family.”

For Edgar, he said the experience had more positives than negatives, reveling in the community aspect of growing up with the other farm worker families. But the circuit periods stifled education and complicated making friends in the local community outside of farm work.

He also noted that moving town-to-town had its challenges, for both children and adults. They were not always welcomed or accepted because of their ethnicity and labor positions.

“I think it gave me a lot of values from an early age about what a community is and how to care for each other,” Edgar said. “I think that was one of the main takeaways; how to take care of each other even when times are crazy.”

As a high school student, he recalls the events and celebrations during the tulip festival season honoring the farmers and landowners. He noticed there was never any recognition for the farm workers, some of which were his own parents and parents of people he knew.

“Ever since I was a kid, I’d have these feelings and thoughts that, if we’re so important to the economy and local culture, why aren’t we recognized?” Edgar said. “I wanted to show people that we were more than what they saw us as, and would ask myself, ‘How do we do that?’”

When he was 15 years old, he began attending marches and meetings, learning from the workers leading the movement. These were held so the local farmer committee could try to start a farm workers union in Skagit County. These events encouraged youth leadership and participation, and would invite all community members to join.

“It was a great educational opportunity,” Edgar said. “It was a chance for us to learn from one another, struggle together and struggle in solidarity.”

When Edgar was a student at Skagit Valley College, he and the student groups were put in charge of leading the marches. This is when he met Rosalinda, where she’d just come from the University of Washington.

At UW she was a foundational member in the Chateau St. Michelle Winery campaign. This was in 1994 when the United Farm Workers of Washington sought to create a binding contract with an agricultural employer, the winery.

She met Edgar and offered her knowledge and experience with organizing marches as well as house meetings. These were small events of five to 10 people, in which organizers met up with community members and workers and discussed local issues.

From then on, they would only see each other about once a year, when a march was being held. At this point, Rosalinda was managing C2C on training wheels.

Edgar then took a break from marches when he moved to Bellingham in 2008, where he worked at the local Albertson’s and the night shift at Haggen’s. He spent his free time coaching a youth soccer club for poorer migrant farm worker children in Mount Vernon, to “fill a void in the community.”

Then, Rosalinda contacted him offering a position to help run C2C’s up-and-coming radio talk show, Community Voz. The show would discuss issues in the local community, immigration reform, farm worker topics and racial profiling.

At the time, C2C was working on a campaign to end racial profiling in Whatcom County.

Edgar said the campaign dealt with problems of police pulling over people of color, with border patrol agency officers listening to the dispatch call. They would often be contacted if the police were suspicious of the civilian’s citizenship and would call border patrol “for interpretation.”

This campaign is where Edgar began his involvement with C2C outside of the radio show, holding house meetings and talking to organizers. From there, he took off into the civic engagement component of involving farm workers in the political decision-making process of the 2012 elections.

One referendum they focused on that year was to provide funding for low-income housing, which was primarily targeted at farm workers. Another big one was R-74 for gay marriage equality.

Edgar said at this time there was never really an attempt on government institutions’ part to engage farm workers and the Latinx community in electoral processes. He said it was his job to figure out how to do that, and how to make their voices heard.

This started the March for Dignity campaign, which focused on immigration reform, and making farm worker voices heard through public gatherings.

“Many community members can’t or don’t vote, because they don’t believe that the candidates represent their voice,” Edgar said. “It was all about creating opportunities for people to participate.”

Edgar said that justice for farm workers takes the form of union contracts and worker cooperatives, as well as fighting for owned land that workers can call home, “So they’re not always moving, like we were.”

C2C is currently approaching its 15th anniversary for their work toward farm worker equity, and have various events planned from August 2018 to October.

This features a community-gathering event at Boundary Bay Brewery in early August, which is also peak harvest season. It will feature a variety of activities and events for farm workers to participate in, as well as meet other members of the community.

In late August, a public discussion event will be held for C2C to discuss the food system on a regional level. In October, C2C will also be meeting with the U.S. Food Sovereignty Alliance Membership to exchange updates and experiences, and discuss future collaborative plans.

“Through the opportunity that [C2C] has given me, I’ve been able to travel all over the country and the globe,” Edgar said. “There’s really no other organization that does a lot of the work C2C does. We talk about food sovereignty, immigration reform, the food system, the economy, climate and eco-feminism.”

Edgar said he’s always been impressed that such a small organization can grow and thrive for 15 years.

“We’re not one of the larger nonprofits that get millions of dollars in funding,” Edgar said. “We’re a small organization, but we’ve done some things that these other nonprofits haven’t been able to do, which is organize communities at the local level.”

Edgar also noted that volunteers and attendants of the events don’t do it for the money, but because they see the visible changes in the local community.

“We’ve been trying to uphold those values and principles of farm worker justice for over 15 years,” Edgar said. “This organization still has the vision and drive to move forward on the goals we set forth.”

Rosalinda remembers her and her sister asking Jesus why he brought them to La Conner. They were angry and wanted to go home because the people they were surrounded by were cold and strange.

“My father said, ‘What you’ve got here is an opportunity,’” Rosalinda said. “‘And back in Mexico, I don’t think you’d have that. That’s all I want to give you — an opportunity.’”