A Globalized Home

The influences that we grow up around help to shape the way we view the world. But what if these influences don’t accurately reflect the world around us?

Personal Essay by MELISSA MCCARTHY

The home I grew up in was pretty run-of-the-mill — a standard, single-level rambler. It was tan. From the outside, it didn’t seem extremely significant or unique. But the people inside gave it a worldly charm.

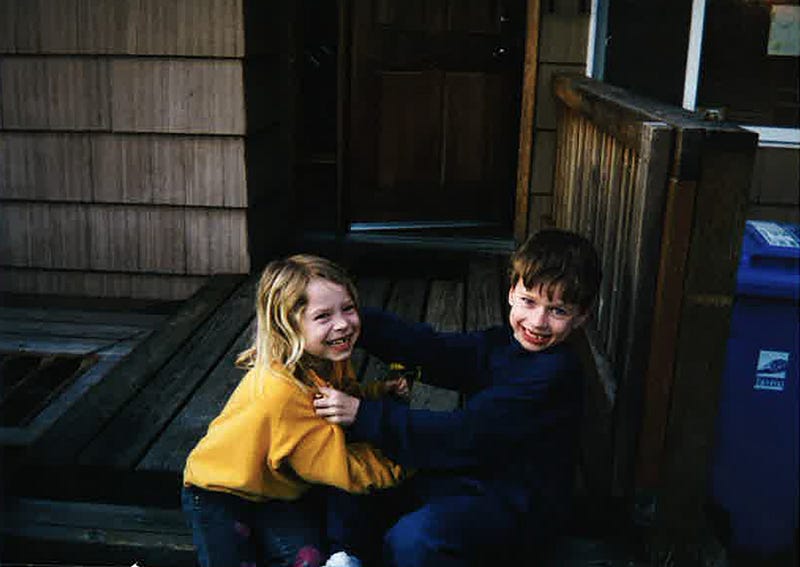

My brother and I were born in that house. We were welcomed into the world by our parents. They came from European ancestry; Irish, German, English, French. In reality, they were white Americans. Children born into racially homogenous families sometimes only see that color of skin until they hit school age. This was not the case in my home.

Within weeks of being born, a line of little ladies had entered our tan rambler to meet me and feed my tired mother. They were originally from Japan. My parents practiced a Japanese-based Buddhism that gave way to friends-in-faith from all across the globe. My little ladies visited weekly for the discussion meetings. They would lovingly chide me for getting dirt all over my nice clothes or not eating enough.

Imagine having six or seven grandmothers all show up at once to dote over you. This was my Sunday reality. They told me about growing up in Japan, about their husbands they met during the war, about coming back with them to America and learning English. I was enthralled. I didn’t even know where Japan was on a globe at this point, but knew I wanted to go there (if only to find the source of Mrs. Haugen’s traditional recipes).

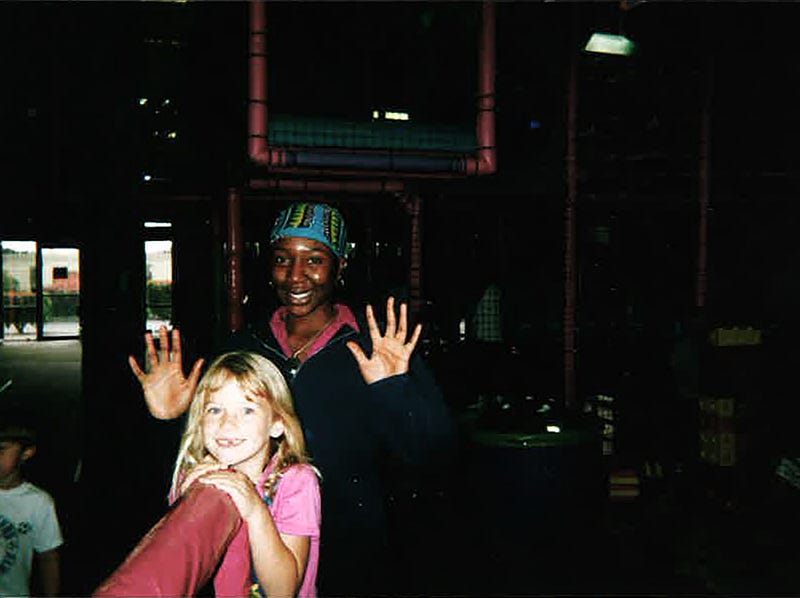

When I had a few years under my belt, I met Evelyn. She was my babysitter and I adored her. Evie (I called her for short) was born in the U.S., but her parents were Ghanaian. Ghana has a matriarchal society and, even though she wasn’t born there, Evie exhibited the strength of the women in her culture. She was assertive and firm, but at the same time kind. I wanted to be just like her when I grew up.

Her father, Kojo, spoke in a low, lyrical voice. Evie’s was higher and fiery. I can’t tell you how many times I sat on her lap and listened to her tell me Ghanaian stories, or talk to her father about their culture — comparing it to the one they found surrounding them. I tried to follow the conversation, but I would eventually fall asleep on Evie’s shoulder, letting the cadence of their accents lull me into a slumber.

Once I entered grade school, my parents had officially split. Raising two kids in a single-parent household is quite the job. So after taking the school bus home, my brother and I would pass our tan rambler for the white one down the street. We would stay with our nanny, Qumar, and her family until my mom got home from work a few hours later. Qumar had moved to the U.S. with her husband, Abdul, and four children from Afghanistan. Abdul had been a judge in Afghanistan before the coup d’etat when they fled the country. They came as refugees to my neighborhood. My brother and I would play with their children, not understanding what they had escaped.

It was around this time that the Twin Towers were hit. I was in first grade and couldn’t comprehend the magnitude of the event. What I did notice was the changes at Qumar’s house. We had to contain our play area to within the yard, but no one seemed to want to play with my brother and me. I remember Qumar’s youngest son informing us that he’d been told to lie about where he was from. His parents told the children to say they were from India should anyone ask. I asked why. He said people were afraid of them because of where they were from.

This was the first time I realized the people who I welcomed into my home, who I loved and looked up to, who shaped me into the young woman I was becoming, experienced the world differently because of the color of their skin.

I recognize how privileged I was to not understand that racism and xenophobia existed until first grade. I realize that the same people who I am describing were aware of this reality as soon as they experienced walking down the street in the U.S. It didn’t take an act of terrorism for them to understand and navigate the dangers of structural racism and inequality.

But after this, I became more aware. I saw the looks, the judgements and sometimes sneers. I saw how my loved ones would tense around certain environments and people. I saw them on guard against a society that didn’t give them a chance to be a part of it.

Those of us with privilege tend to either be blind to these realities or perpetuate them. Both can be extremely damaging.

I tell this story now because people of color in our country are facing more blatant and aggressive attacks than I can remember during my lifetime. Across the country, white supremacist groups are transitioning from the shadows to the limelight.

I understand that the influences around you when you grow up shape the way you view the world. I understand members of these hate groups come from racially homogenous households. I share the story of my tan rambler to remind you that when you open up your doors to those who are different from you, the people who come in can reflect the complexity of the world.

Because of the exposure I was lucky enough to have as a child, I experienced cultures from all over the globe. I saw unique cultural practices, heard stories, tried new flavors and had many other wonderful, enriching opportunities as I grew up. I was also able to see firsthand the ways in which xenophobia damages lives. But I’m glad I did, because it removed the veil of privilege from my eyes.

It is at this time that we most ask ourselves, do we want to perpetuate modern day slavery in the form of trafficking of immigrants or imprisonment of people of color? Do we want to continue to subdue and subject those who come from a different cultural or ethnic identity so that “white nationals” can maintain socially constructed superiority? Do we want to continue to exploit, spread hate, and be blind to the horrors we are committing? This is neither humanitarian nor sustainable. So I encourage you to open your worldview to encompass the world in its entirety, in all its complexity; in its diversity and in its damage. Turn your own tan rambler into so much more.