Portraits of Pacific Northwest Writers

Exploring the creative minds of Bellingham

By Kira Erickson

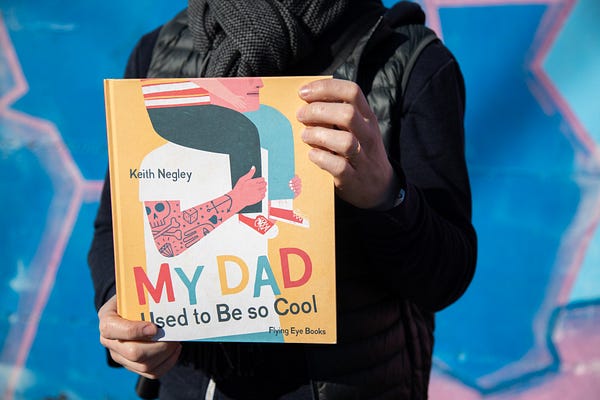

KEITH NEGLEY

When Keith Negley started writing children’s books, he didn’t intend for them to tackle societal issues like toxic masculinity. At the time, interactions with his son Parker inspired his books.

When Parker asked about the collectable skateboard on his wall — a trademark of his cooler days — Keith wrote a book called “My Dad Used to Be So Cool.” When Parker was frustrated with how he cried after a soccer game, Keith wrote “Tough Guys Have Feelings Too.”

The former is “a wink and a nod” to all the formerly cool dads out there, Keith said. The transition from playing in rock bands and riding vintage motorcycles to fatherhood wasn’t always fun for him. But he realized the coolest thing he can do now is spend time with his son. The book echoes this sentiment.

“Tough Guys Have Feelings Too” sprung from the conversation Keith wanted to have with his son about the complex emotions he felt. There are a lack of picture books which address this, so Keith wrote his own.

“I noticed that all the cartoons we were watching were all superhero geared and there’s a lot of fighting and adventure happening,” Keith said. “But they never show you what happens when they have a bad day. You never get to see how Batman deals with having his feelings hurt.”

Keith resembles a big kid himself, from his black Converse low tops to the intricate and colorful designs on his arms. He doesn’t consider himself to be “hip” anymore, but he seems much younger than his four decades.

Keith currently freelances as an editorial illustrator for The New York Times and The New Yorker but hopes to make writing children’s books his full-time gig.

“I’m not much of a reader. I do my best to read, and I try reading, but it usually just puts me to sleep,” he admitted with a laugh. “But I love to tell stories with pictures. As an illustrator, that’s first and foremost what I love to do. That was my entry into being an author.”

For his third book, Keith wanted the protagonist to be a woman, something he rarely finds in children’s books. He began doing research to get inspired from a real woman in history. That’s when he discovered Mary Edwards Walker, the only female surgeon serving in the Civil War. She was often criticized for wearing pants instead of dresses.

“This idea that there was a time where women couldn’t wear pants, I thought, ‘This is crazy. What if she’s a little girl going to school wearing pants and the whole town freaks out?’” he said. “That’s the whole premise of the book. It’s not a biography, it’s just inspired by her attitude and her life.”

Debunking gender roles, like showing defiant women and sensitive men, have been important in the books he’s written so far. Keith also wrote “Mary Wears What She Wants” when bathroom bills and the rights of transgender people were challenged.

Even though they have a limited number of pages, picture books take just as long to write and publish as any other type of book. His book based on Mary Edwards Walker took three years.

“Pacing is really important in picture books because you only have 16 to 20 spreads and you have to keep it interesting. You have to keep the person wanting to turn the page and you can’t have any lulls,” Keith said. “Every word and picture, every element needs to propel the story forward, otherwise it shouldn’t be in there.”

Keith published his first two autobiographical books through a boutique publisher in the U.K. by independently contacting them, which is atypical in the publishing industry. When they weren’t interested in his pitch for Mary’s book, he found an agent and got it published through a subset of Harper-Collins.

As for the books he plans to write in the future, he has a few ideas. They may be pure fiction and include kooky characters who get into crazy situations, he said.

For Keith, writing what he knows may sound cliché, but he doesn’t know how to write anything else.

“Everything an artist makes is a self-portrait on some level. I feel like authenticity is extremely important because your audience wants to relate to the work,” Keith said. “I think the best work — the work that’s the most successful — is the work that’s relatable. So people can come to it with their own baggage and their own stories and see themselves in the work.”

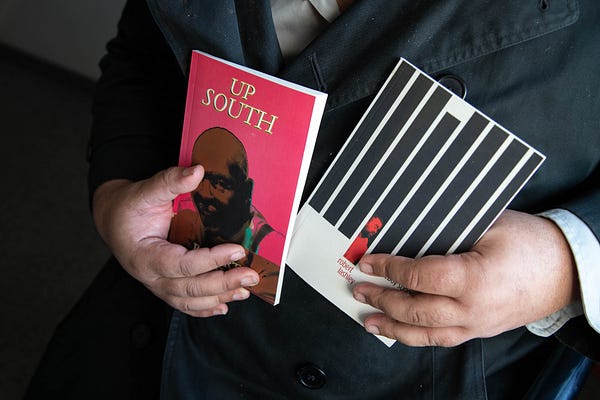

ROBERT LASHLEY

Robert Lashley doesn’t waste a single word as he speaks. The poetry of everyday speech comes naturally to him, but he wasn’t always interested in being a poet. He began writing poems about the Tacoma community where he grew up while he was dealing with personal health issues.

“My uncle was the first poet in my family, and I loved hearing my uncle talk about poetry. But I was agnostic about doing it personally,” he said. “When my grandmother was murdered, I just wanted to erase all those memories that I had had of my family before then. But when I went to get healthy again, writing poetry was my way of connecting back with my family before my grandmother’s murder.”

Robert didn’t understand his poems were unconventional, breaking the rules of what poets and black poets were supposed to write. He didn’t realize he was expected to write slam poems that were messages for the larger community.

While reading his work at a gig in Portland, Small Doggies Press, an independent publisher, discovered him and convinced him to publish his work. He didn’t have an agent and still feels spoiled by the good fortune.

“Being the first African-American poet to have a bestseller in the state of Washington, a lot of people see me as a sort of standard of authenticity,” Robert said. “But before, when I started, people saw me as a sell-out, as somebody who would not constantly praise black men all of the time. There isn’t one story. There are 43 million black people in America, there are 43 million ways to be black.”

While he was successful in having a bestseller, he doesn’t see a lot of the profit. With every book sold from his publisher’s website, Robert makes around five dollars. On Amazon, he earns only 17 cents per book sold. He doesn’t deny the company offers networks for self-published authors — a few of his friends have chosen that route — but the wage gap is unsettling. The Authors Guild reports Amazon controlled 85 percent of the self-published market in 2018.

When writing poetry, Robert tries to look at his work in three different ways. First, does this need to be said? Second, am I the one who needs to be writing this? Third, am I writing it well enough? He said he has two warring impulses when writing: To organically create drafts versus to edit, edit, edit. The whole thing is an elaborate magic trick to make something seem both organic and well written.

In a town where monthly art walks, independent bookstores and movie houses flourish, an appreciation for the arts seems to be a priority among its denizens. Robert enjoys Bellingham for the nature and isolation it provides, but he hasn’t found the local art community to be very welcoming nor inclusive.

“I’ve toured around the country, I’ve seen different scenes. This might sound shocking, but I really believe that the Fairhaven poetry scene in Bellingham is the most racist I’ve ever seen,” Robert said. “When I started as a young writer, and I’d go to open-mic scenes, people would give me their keys, as if I was their valet. People would make jokes that I’m only there to steal wallets. When I would try to talk books with writers, they would laugh, as if it was absurd that I would know this person.”

He has found more of a sense of community and culture in Tacoma, where he works for an artist collective, Seattle and other parts of the U.S.

Robert acknowledges lyric poetry, his style, is not for everyone. He wishes the degrading comments he’s received at poetry readings in Bellingham had been about his work instead.

“I think that too many of us have this habit of scrutinizing someone’s personal preference, and thinking of it as a crime,” he said. “[Authenticity] means writing something that I can look myself in the mirror and be proud of. It means planting my tent as a writer and making the tent as big as possible, knowing that you can’t get everybody, but to just try. There’s a cost-benefit analyses in that, especially if you’re an outsider, an outside writer. That’s authenticity to me.”

JANE WONG

Poet Jane Wong will always remember the Chinese-American restaurant she grew up in. Her family served inauthentic Chinese food to American customers who believed it was authentic. Since then, she said her definition of authenticity has been murky at best, mixed with how people perceive us and how we want them to perceive us.

“For me, if I were to be authentic in a poem, I almost feel like it would have a veneer of something that’s not authentic,” Jane said. “I can’t write about authenticity without also writing about inauthenticity, or what people expect of me.”

Like Robert, there are certain implied expectations for her when she is writing poetry as a Chinese American. These include the story of a journey from China to the U.S., a desire for a fraught space between two worlds or the usage of symbols like chopsticks and dumplings.

She acknowledges sometimes she has written about these topics, but the expectation they are the only things she can ever write about isn’t realistic.

“I can write about heartbreak. I don’t have to write about being Chinese American all of the time. Be proud of moments when you do write about them, but also allow yourself to realize you can write about anything as long as it feels honest to who you are and all the parts inside you,” she said. “You’re made of multiple selves and multiple stories of joy and death and terror and displacement, colonization, but also maybe carrots and love poems.”

Jane often writes poetry from her mother’s point of view. She begins with a truth from a seed of a story her mother told her, matching it alongside old photographs of her mother to see what clothes she wore.

“I find the poems where I wasn’t there, and I have to speculate, more enjoyable to write because it requires me to step outside of myself and push myself to imagine those stories,” Jane said. “When I’m in my own headspace, it can feel a little claustrophobic, so I love when I write in my mom’s voice.”

These poems of Jane’s are her mother’s favorite. Jane describes her mother as an extrovert, unlike her, and someone who loves the attention her daughter’s work has given her.

Jane also writes with visibility in mind. As someone who spent most of her life thinking she didn’t have a voice, she finds the representation of women of color and children of immigrants important in everything she creates.

“I hope that people reading my work really recognize the power of voice,” she said. “I hope those stories inspire readers to consider different perspective and have more empathy in the world. The personal is political.”

She recognizes the need for poets of color to have spaces to come together. When she lived in Seattle for six years, she ran a reading series called Margin Shift which highlighted writers of color, moving them away from the margins of society to the main focus.

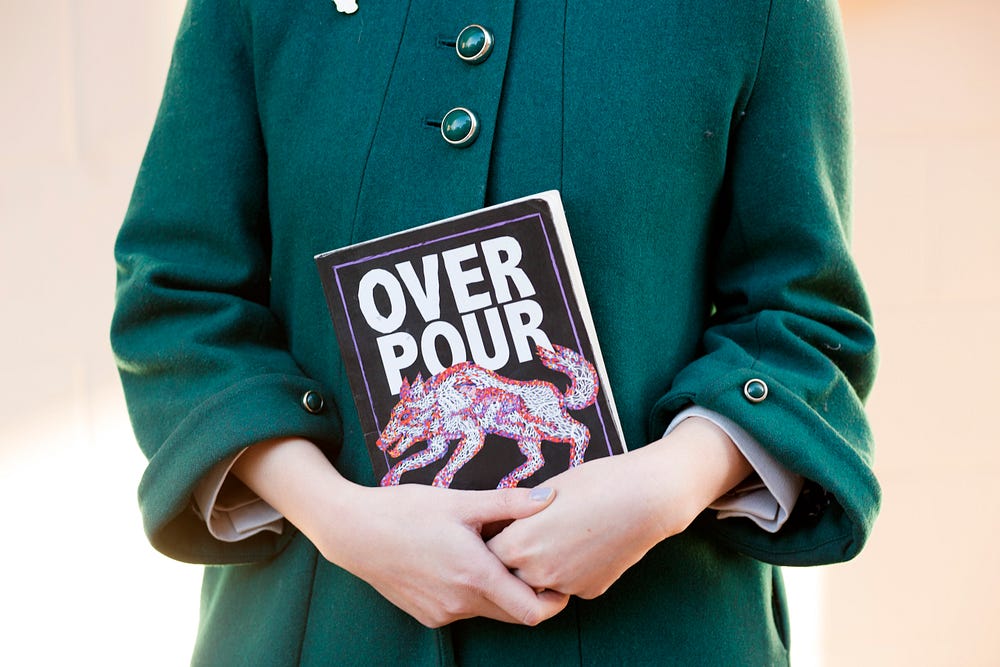

As a professor at Western, it can be difficult for Jane to balance her time for writing with teaching. If she gives students prompts in her classes, she will often write along with them. Her first book “Overpour” was published in 2016 by a small, experimental press. The norm for poetry, Jane said.

“It was a wonderful process,” she said. “Because poetry has small presses, you work very closely with the editors in a way that feels very intimate because there’s just this very close connection between editor and writer.”

Jane’s style of writing poetry can be startling. She often writes about raw meat, rodents and insects. She points out a rat figurine one of her students gave her, turning it around on top of a file cabinet in her office to face a battery-operated tea light. She switches it on.

“A lot of my poems are grotesque, they tend to be beautiful ugly,” Jane said. “I would love for the world to look at something that would be deemed ugly, like a cockroach, and say, ‘You too have a place in this world, and you too have a sense of smell and touch and have a history behind you.’ Exulting that which is small, I like that idea too.”