Bigfoot Doesn’t Care If You Believe

From ancient folklore to guided expeditions, Bigfoot is alive and well in the Pacific Northwest

Story by Sam Fletcher

Drizzling rain breaks on the pavement by Squalicum Harbor, as it has for the past week. I stand waiting, equipped in snow boots, a rain jacket and headlamp, wondering how I will recognize my tour guides.

When they pull up, I realize the thought is ridiculous. If the giant white van with LED spotlights and a ladder didn’t tip me off, it was the vibrant illustrations of mountains, forests, and — of course — sasquatches.

My guides, Joey Sternhagen and Ray Kolean, greet me with bright smiles and handshakes. Without much delay, I hop into the front seat, and we head out.

Bigfoot came up in conversation the very day the two met in Alaska, each guiding groups with respective charter fishing companies. Both had been searching for the disputed creatures their entire lives and clicked instantly.

In 2017, they came together to found The Bigfoot Adventures.

While they left the Alaskan wilderness behind, they’re still fishing — but they might need a bigger net. Together they guide Washingtonians through rural areas where sasquatch sightings are frequently recorded.

Sternhagen tells me they have brought along skeptics and believers, young and old, and those who start the tour chuckling usually change their tune by the end. I’m pretty confident we won’t find bigfoot tonight, but I try to keep an open mind. There is more to the legend than just blurry photographs.

On the official website of the Bigfoot Field Researchers Organization, there are reported sightings of bigfoot in every state but Hawaii. Whether these accounts are based in truth, it is certain that there are more sightings recorded in Washington than any other state by far.

As we cruise down lonely highways and mountainous backroads, Kolean and Sternhagen have stories of sightings at almost every mile marker.

“Washington is the heart of it,” Sternhagen says from the backseat, gazing at the twists of Mount Baker Highway through hard-working wipers. “You go out on the Olympic Peninsula, you can’t talk to anyone out there who hasn’t had an experience with bigfoot, so this is the perfect place to take people out.”

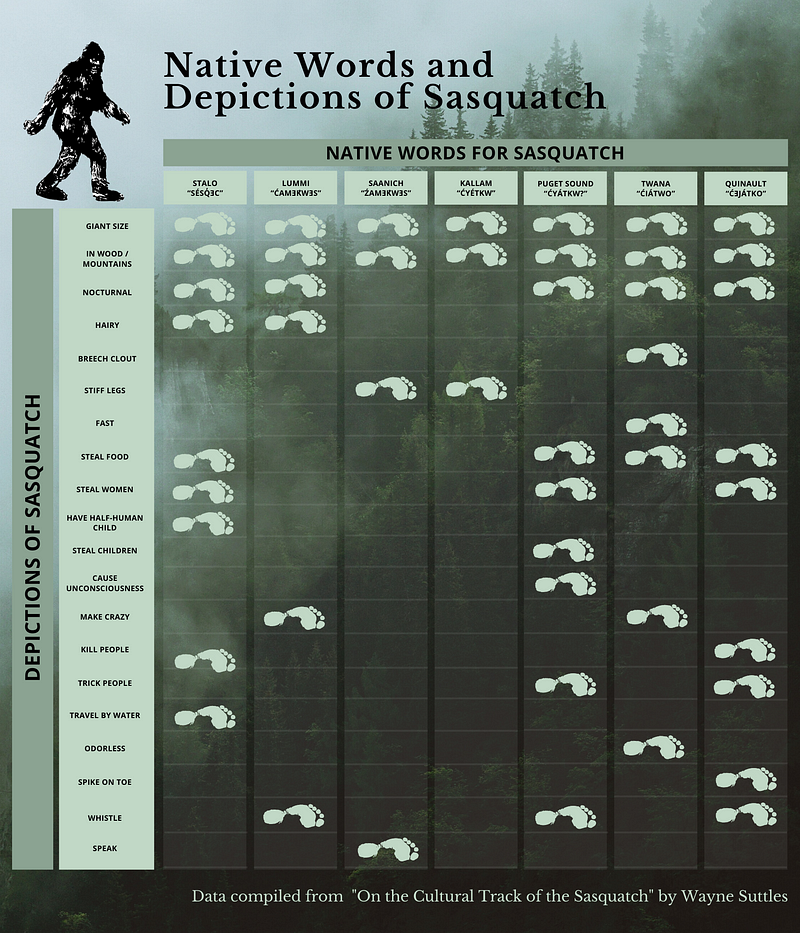

According to Seattle anthropologist Wayne Suttles, the word “sasquatch” is an Anglicized version of “sésq̓ǝc,” meaning “wild man,” from the Halkomelem language of the First Nations people of British Columbia.

But there are other words for bigfoot. One for nearly every Coast Salish tribe, in fact.

“Most, if not all, of the Coast Salish of this area seem to agree that there are large, man-like beings in the woods and mountains who differ from human beings in various ways,” Suttles writes in his 1972 paper “On the Cultural Track of the Sasquatch.”

Suttles does not argue whether this belief is of a physical being or a mythical one, as native people have not held such a dichotomy. In the same reports of elk, bears and beavers, are reports of two-headed serpents, thunderbirds and sasquatches.

This does not mean that the mythological elements of these stories are not grounded in truth. Famous Klallum folklore tells of prophetic beings warning their village of a great flood in the area. In the 2000s, Geologists of Portland State University, Western Washington University and the University of Rhode Island confirmed this flood occurred.

Because the spiritual and the physical worlds are equally real to Coast Salish tribes, Suttles says, what is seen in a “vision” experience and what is seen as an “ordinary” experience are not differentiated in native stories and writings.

According to a blog post written by the late Steve Pavlik, a professor at Northwest Indian College, bigfoot has always been a spiritual being — a shapeshifter even — thus proving its existence is impossible.

Kolean has heard this perspective many times, but holds an entirely different one.

“Anything that leaves tracks in the mud, leaves hair samples, sh*ts in the woods, hollers like any other primate does, I just don’t think there’s a lot of them out there,” he says. “And I think the ones out there are very adept at staying hidden.”

Because the majority of sightings and evidence are found at night, Kolean believes sasquatches are nocturnal creatures that hide during the day.

The sun is starting to set when Kolean eases the van to a halt beside the North Fork of the Nooksack River, where we retrieve the first trail camera. Tied to a pine tree and pointed at the rapids, this camera snaps photos anytime movement is detected. Though the primary goal is to capture footage of bigfoot, Kolean and Sternhagen prove to be enthusiasts of all kinds of wildlife as they analyze the surrounding mud for tracks imprinted by cougars or elk.

As we cruise down lonely highways and mountainous backroads, Kolean and Sternhagen have stories of sightings at almost every mile marker. Along these paths, sasquatches have reportedly chased a couple down the mountain, howled so loud that campers abandoned their gear and even saved a young camper from hypothermia.

According to Suttles, stories like these have been blossoming in the area since time immemorial. Sasquatch-like beings of Coast Salish folklore are often depicted as tricksters, thieves and kidnappers, depending on what tribe is telling the story.

“[The people of the Lummi Tribe have been] so amazing about sharing their stories [with us]” Sternhagen says. “I had one gentleman flag me down to tell me about his experience about sasquatch, and his mother’s, and grandmother’s and his grandfather’s. There’s not as much stigma around it when it comes to the tribal stories, so all of the people I’ve run into that are native are just so open about it.”

Old folklore depicting nocturnal, 8-foot-tall, hairy, bipedal creatures knocking on trunks and howling is not so different from reports in Whatcom County as recent as 2018.

[embed]https://uploads.knightlab.com/storymapjs/b10267ba983ab06a7ed9763076235bec/bigfoot-sightings-in-washington/index.html[/embed]

The site of the most recent report — 2,500 feet up Sumas mountain — is our next stop. On a narrow dirt road that tilts the van vertically, we press upward through increasing snow. Now hours into the night, at 1,600 feet, we climb out and fix chains on the tires before proceeding. The air is much colder at this elevation.

Optimistic that the van will make it, we push forward, windows turning a frosty white. When we finally reach the top of the mountain, we pause to warm up around a fire. The heat becomes a nice break in the trip as our clothes absorb the scent of burning Oregon yellow cedar gathered by my guides the previous week. It’s the most potent pine I’ve ever smelled.

As the three of us sit with tea and cocoa, Kolean shows me a cast of a 17.5-inch footprint from where he grew up in McCleary, Washington. He recounts the time when he successfully lured in a sasquatch by blowing into a coyote call, a handheld device, not far from the same area.

When Kolean demonstrates, the call sounds like a squealing rabbit. It lures predators that come to feed on potential prey before it perishes. Among the interested parties, Kolean says, is the sasquatch.

He pulled the flashlight from his pocket, revealing a large sasquatch every bit of 8 feet tall, grimacing with a full mouth of human-like teeth.

At Kolean’s high school graduation party, the whole class camped outside McCleary. He’d been calling in that area for weeks following the discovery of tracks and broke away to continue his search.

After four calls and no response, he heard the snap of a stick behind him.

He pulled the flashlight from his pocket, revealing a large sasquatch every bit of 8 feet tall, grimacing with a full mouth of human-like teeth.

The creature stood within 10 feet of Kolean. It had short hair across its chest and a large sagittal crest on its skull, common among apes.

After five seconds, the beast retreated into the bushes.

“He could have crushed me like a toothpick,” Kolean says with a voice drenched in passion.

His eyes are wide as he relives a moment ingrained in his memory. With a sighting like that, it’s easy to understand the ambition that has carried him into this career.

As our cups empty, we gather our gear and hike uphill to retrieve the trail camera, aided in the darkness by the bright beams of our headlamps.

Kolean and Sternhagen are especially excited because the camera has been fixed to a tree for six weeks. While they normally check their cameras every week, the previous snowfall blocked the steep roadway.

Halfway up the slope, Kolean draws my attention to enormous human-looking tracks in the snow. Absorbed in the guides’ eager curiosity, my heart batters too.

I find myself peering at each track intently as I walk beside them, looking for any semblance of toe prints.

But I am disappointed. As the snow thins, we realize the tracks are just a hiker’s bootprints, simply widened from snowmelt.

When we reach the camera, we shut off our lights and take turns blowing into the call. We clack a knocker, which creates a loud echo down the mountain — a way sasquatches reportedly communicate and locate each other. We whoop and howl, and Sternhagen proves to have the most ape-like yell.

But no sound returns.

We pull out night vision and infrared lenses and survey our environment. Not even a rabbit leaps.

On a drive through Whatcom County, bigfoot can be seen on bumper stickers and coffee shop logos. Through stories and art, too, the sasquatch continues to prove its indisputable influence on the area.

Regardless of whether Kolean’s biological question about sasquatches’ existence is ever answered, Suttles certainly raises an interesting anthropological one: Why do so many people believe?

According to author Robert Alley, many Coast Salish nations such as the Kwakiutl people of British Columbia and the Tlingit people of Alaska have art depicting bipedal apes from long before any type of ape was brought to the continent.

Sasquatch-like figures have been reported in every continent except Antarctica, according to data from Google Maps. These sightings vary by name but hardly by description.

The Nepalese yeti, Australian yowie and South African waterbobbejaan are just a few examples. Bigfoot is seen across the world, in vision quests and shaky video cameras alike, with hundreds of fresh sightings and stories each year.

On the bumpy road back down the mountain, Sternhagen attempts to read the footage recorded by the cameras. They hold photos of hikers, a squirrel and some snowfall. But no bigfoot tonight.

I’m reminded of the occasional unsuccessful fishing trip with my dad. As we packed up our gear, he would always say, “That’s why it’s called fishing, not catching.”

Kolean smiles when I tell him this.