Ingat ka

A journey of embracing one’s identity as a child of immigrants.

Story by Shaina Yaranon

It’s impossible to pinpoint the first moment I grappled with being Filipino American. For as long as I can remember, I just felt like I didn’t belong. At school, I was often the only Filipino in my classroom. And at home, I couldn’t understand the conversations that my parents had with each other in their own language.

My parents immigrated to America from the Philippines in the 1990s because their greatest hope was for their children to have better lives — and the U.S. was their solution. After my dad made it to Seattle, my mother and older sister didn’t join him for six years. My parents left behind their world in exchange for another.

I was born in America, but I always struggled with the concept of home. I loved Seattle, but home was also a far-off place. It was across the Pacific Ocean, a group of islands with rolling mountains, turquoise waters and sandy beaches stretching as far as the eye could see. A land filled to the brim with people who looked like me.

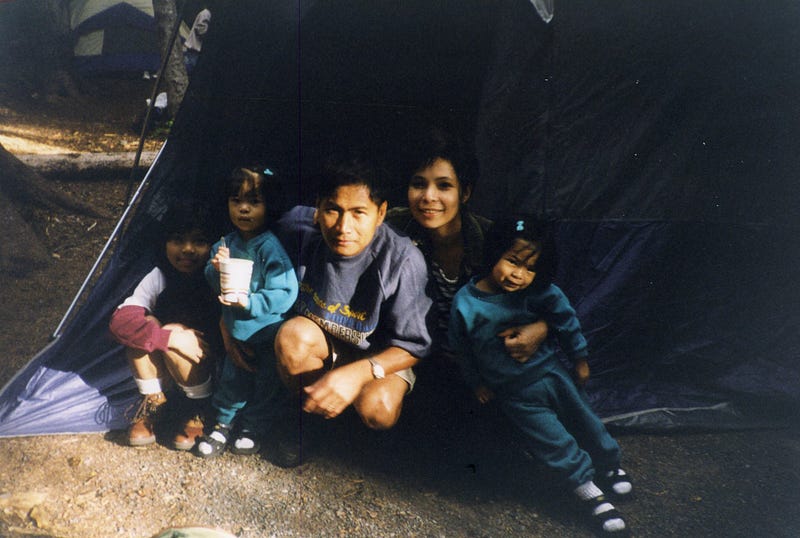

As I grew older, I always longed to find my roots. I spent long nights flipping through the dusty, worn-out pages of family photo albums while my parents shared stories of their past lives, their eyes filled with a childlike wonder.

But looking through photo albums could only do so much. All I ever wanted was to feel at home and to experience my heritage and culture for myself. When we returned to the Philippines as a family in 2008, my wish came true. My parents’ homeland was vibrant and full of life, from the bustling outdoor marketplaces and the bright jeepney cars to the rice fields blanketed in brilliant shades of green. The humidity sunk into my skin, and I felt safe in the Philippines’ warm embrace.

When the near-constant rain subsided and the sun filtered through the palm trees, I thought back to the photo albums back in America. I was home now, it was real.

On our last day, my relatives threw a goodbye party. The horizon was painted with vivid hues of scarlet and gold as the setting sun slipped beneath the crashing waves. The sounds of laughter and singing echoed from the pavilion. My sister and I ran across the beach, our feet softly padding against the sand beneath a canvas of a dark sky speckled with stars.

It was across the Pacific Ocean, a place with rolling mountains, turquoise waters and sandy beaches stretching as far as the eye could see. A land filled to the brim with people who looked like me.

At the end of our visit, everyone hugged each other goodbye. “Ingat ka,” they told each other, a saying that translates to “you take care” in Tagalog. It’s a saying with a lot of love built in — an affirmation that Filipinos look out for one another.

I didn’t want to leave. It was where I belonged. I couldn’t even imagine how my parents had felt leaving this beautiful country and their family and friends behind. How could I return to the States after experiencing all the warmth of the Philippines?

Back in Seattle, I felt more out of place than ever.

“Where are you from?” a man asked, his voice raspy. He was an older fellow. His green eyes seemed kind and filled with curiosity. It was eight years after our return and a stranger was peering down at my sister and me as we stood in line at a bookstore. “Oh, we’re from here,” I told him cheerily.

His eyes narrowed for a flash of a second. “No. Where are you really from?”

I suddenly felt glued to the floor and offered a weak smile back at him, unable to hide all the hurt I felt. His words stung. My sister’s eyes flickered to mine and she spoke up, “We’re Filipino.” We made tense small talk with him, said our goodbyes and hurriedly walked out of the store clutching our books, shaken to the core.

As I’ve grown older, I’ve stumbled across many frustrating situations like this. Situations where I couldn’t articulate the emotion and anxiety of feeling like an outsider.

People see tan skin and black hair and automatically think foreigner.

My family all believed America was a welcoming place with boundless opportunities and open arms, yet again and again, we are greeted with discrimination and ignorance.

These moments, though disheartening, made me realize one thing: even in the midst of endless uncertainty, I knew I couldn’t let people define my identity, and that I needed to prove to myself that I was meant to be here.

Part of that journey was enrolling in college. In the winter of 2017, my sister and I transferred to Western Washington University. It was our first time moving away from home, and my dad drove with us to help us settle in.

As we wound through the Chuckanut Mountains, I sat in the passenger seat with my hands wrapped around my knees, staring absentmindedly at the steady pulse of traffic buzzing by and the endless rows of frozen pines. Beside me, my dad was concentrating on the road ahead, but I could tell something was wrong. There was a twinge of sadness under his smile, and his hands were trembling on the steering wheel.

After helping us carry our belongings into our new home, my dad got into his car and waved goodbye. As I waved back, my heart skipped a beat. I repeated in my head that they would only be an hour and a half away and watched as his tail lights faded into little specks in the distance.

My family all believed America was a welcoming place with boundless opportunities and open arms, yet again and again, we are greeted with discrimination and ignorance.

I didn’t even unpack the first box before my mother called. She rambled on for what felt like an eternity. I assured her, as much as myself, that I was excited for what was ahead and that I wanted to be here.

Then the line went quiet. After a slight pause, she broke the silence.

“Ingat ka, anak. I love you,” she said softly. You take care, my child. I love you.

Her words opened the floodgates I had desperately tried to hold back. Ingat ka. The words rang in my head. Even though I hear the phrase daily, for some strange reason at that moment in time, it stunned me into silence.

I peeked through the cracks of my window blinds; already late in the day, the winter sun had cast its last rays on the tips of the hemlock trees. I thought anxiously about the days to come — my first classes, graduation, a career.

And then it dawned on me: My parents got me here. They paved the way for my sisters and I.

With the phone still clutched against my ear, I pictured my parents sitting together at home, seeing for the first time the decades of struggle present in their weathered brown eyes — physical evidence of many tumultuous, stormy waves, the catalyst for my own strength.

My muddled thoughts started to clear. I finally began to embrace who I am: unabashedly Filipino American, unendingly proud of the many places and people I call home. I knew what I wanted to say and what I must do.

“Ingat ka. I love you too, Mom.”