If Money Could Buy Happiness

A lesson on sunk cost fallacy two decades in the making.

Story by James Ellis

I distinctly remember a class project from elementary school, probably during the fifth grade. The prompt was, “Where do you want to go?” and we could interpret it however we liked. Our responses were typed, printed and then cut into strips to be arranged in the shape of a tree.

Some students had fun with it. One person wrote, “I want to go to my imaginary palace,” another, “I want to go to bed so I can sleep,” But most were earnest, wishing to travel, or go to the school of their choice.

I was one of the students who took the exercise seriously, and our teacher brought a couple of us outside for a photo. We took turns getting our portrait taken with a small whiteboard to display our destinations. One girl wanted to go to the University of Washington and wrote, “Go Dawgs!” in the corner.

I wrote, “college.” No embellishment, nothing but a means to an end. I didn’t understand why they made a big deal of it. It wasn’t specific, funny or particularly creative. I thought it was a boring answer.

Of course I intended to go to college, that goal was etched into every fiber of my being. Going to college meant having options, something my family lacked when they emigrated from South Korea in the 1970s.

My mother and her sisters grew up in Los Angeles and regularly couldn’t afford McDonald’s. An opportunity to make money on Alaskan fishing boats brought most of the sisters to the Pacific Northwest straight out of high school, and they’ve worked hard ever since to make sure their children wouldn’t have to struggle like them.

The plan growing up, as I understood it, was simple enough: work hard now, go to college, work less later. For the time being, I could just worry about getting good grades and I would be on track to happiness. Probably.

I wasn’t clear on the details, and I never had to figure them out because school seemed to validate my facile mission. Hard work and creativity gave way to fulfilling criteria, and I could coast through grade school without thinking too critically about my future.

The plan growing up, as I understood it, was simple enough: work hard now, go to college, work less later.

I still worked hard, of course. The years I spent conflating my grades with my self-worth left me fixated on perfection, an unsustainable standard as school became more challenging. I doubt I would have graduated if not for the quiet panic ever present in the back of my mind, reminding me to keep my eyes on the prize.

I was burned out by the time college application season rolled around, and I achieved my life’s goal with no fanfare. I submitted an application to Western because I knew I would get in. I knew nothing of the school apart from its acceptance rate; I hadn’t even seen the campus. None of that concerned me, I just needed to go to college. The height of the bar didn’t matter as long as I could clear it.

I would attend Western beginning fall 2016. I had more than 40 college credits from advanced classes I took in high school. I was undecided on a major, but I had plenty of other general university requirements to fulfill in the meantime. All my hard work had paid off, I thought. I have something to show for all my stress and frustration.

Cut to a couple years in when I reached the credit cap for undeclared students. My class registration would remain blocked until I declared a major. I chose journalism because I had a knack for writing. I could change it later if I wanted to.

Ironically, forcing my hand got me thinking. I knew I was treading water, but I didn’t stop to wonder why. I never considered the fact I had no idea what a “good job” meant to me.

I was never emotionally invested in that goal, despite understanding intellectually the importance of a university degree. There was no point in worrying about something guaranteed to happen, so I grew complacent, and only got away with it in grade school because my choices were largely inconsequential.

I never learned to appreciate the value of having choices because, like my family before me, I operated on necessity. All that time I should have spent deciding what to do with my life, I spent worrying about going to college. Once I was confronted with a decision to make, I realized college was never “the” answer. It was simply one place I could go to find answers.

The plan was inherently flawed. For one, college doesn’t give people good jobs. Lucrative interests give people good jobs. The professions with the highest average wages may require professional degrees, but those careers won’t help those who aren’t interested in them.

Even then, studies suggest money alone doesn’t make people happy. In fact, expecting money to bring us happiness may make us sadder. A study led by Lora Park, a psychology professor from the University of Buffalo, found that people who base their self-esteem on their income tend to focus their energy on increasing their capital at the expense of their personal relationships, which leads to feelings of sadness and discontent.

“When we pursue financial success as a way to boost our self-worth, we feel great when we succeed but terrible and worthless when we feel like we are falling short of this goal,” Park wrote in an email. Park cited studies from a variety of sources that concluded that using money to help others led to greater happiness than using it for self-enrichment.

I never learned to appreciate the value of having choices because, like my family before me, I operated on necessity.

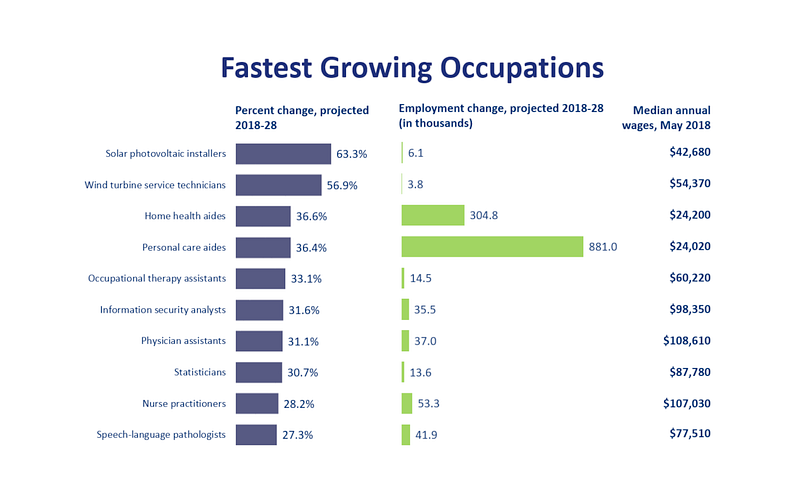

Additionally, those who graduate with a degree outside of high-paying professions may not find work from their interests. Employment projections from the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimate that just three of the 10 occupations with the greatest expected growth will require a bachelor’s degree: registered nurses, software developers, and general and operations managers. Personal care aides and solar photovoltaic installers, the occupations with the greatest projected increases in employment in numbers and percentage respectively, only require a high school diploma or equivalent. Four of the top ten growing professions require no formal education.

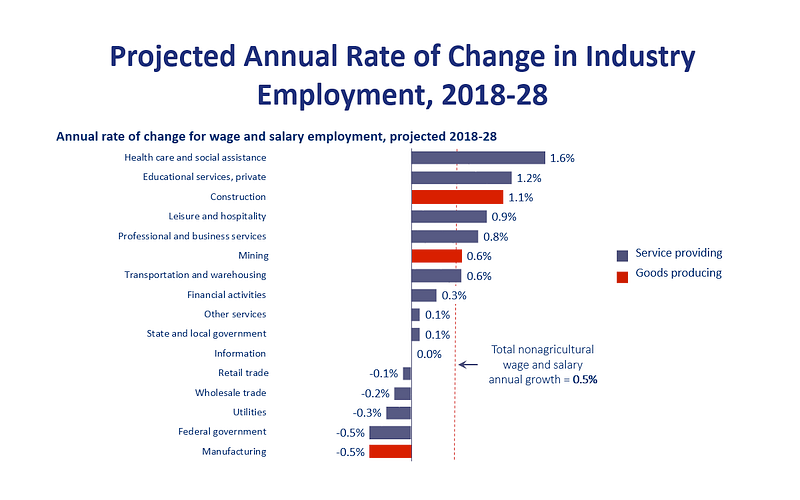

And while some jobs grow, others languish despite money to be made. Skilled trades, many offering above average salaries, struggle to hire workers as university becomes the default first step in career paths. Reports find that schools do not adequately inform students about Career and Technical Education, but programs like Career Connect Washington work to improve public perception and awareness.

In fact, coronavirus has demonstrated our reliance on this skilled work. In our time of crisis, many of the services we declare essential don’t require a college degree. The white-collar jobs glamorized in our entertainment and encouraged in our schools have disappeared into the background as truck drivers, food handlers and warehouse workers keep the nation afloat.

Maybe the answer I gave in elementary school didn’t resonate with me because I never had to explain it. It’s easy to write “college” on a whiteboard, but if they asked me to explain, they would realize it was a reflex for me. A hollow response I knew would merit praise.

The plan was inherently flawed. For one, college doesn’t give people good jobs. Lucrative interests give people good jobs.

If I could amend my answer, I’d want to visit Berlin. I like how architecture can illustrate the passage of time by juxtaposing buildings from different periods, and German architecture is especially diverse. I also love kielbasa and Poland is directly adjacent to Germany.

Instead, I took the project so seriously I couldn’t even name an actual school. Well, I’m going to college, but I have too many factors to consider before I can say where with any certainty. More than me, it was my family’s legacy I had to contend with, so I couldn’t bear to set their expectations with a school I wouldn’t eventually attend.

I recently looked up that University of Washington girl. It turns out she went to Loyola University.