Mountains Call the Shots

A day of snow-filled fun can quickly turn to tragedy in unpredictable mountains.

Story by Alex Moreno | Photos Courtesy of Grant Gunderson

At 3,500 feet elevation walking through the White Salmon parking lot toward the lower lodge and chair 7 at the Mount Baker Ski Area, you’re surrounded by smiling faces, the smell of french fries and, if it’s not a winter storm, beautiful sights of peaks and staggering mountains. Anyone can buy a ticket, and once you have, the phrase “your safety is not guaranteed,” becomes a part of you in bold letters. The mountains don’t care who you are or what you want to do. They can quickly turn a day of fun recreation into a life-halting tragedy.

Split-second reaction. Life or death. Blackness. Snow like cement. No movement. Muffled sounds. Screaming into snow. Solitary confinement. Helpless. Trapped. Darkness. Light?

Avalanches kill more people in national forests than any other natural disaster every year. Avalanches aren’t the only thing to be worried about either, other common causes of death are people losing their orientation and tree wells, which are naturally occurring gaps around trees that act as winter’s version of quicksand.

Dangers in the mountains aren’t always easy to predict, unlike knowing not to drive fast when roads are icy or not to sail a boat when the waters are violent. Mountainous terrain looks beautiful and manageable because the lurking danger doesn’t lie on the surface, the trouble lies below.

Avalanches occur because of instabilities in the bonding of snow layers. They are typically triggered on slopes greater than 30 degrees steep with high danger after heavy recent precipitation, large fluctuations in weather and in areas loaded with snow from the effects of the wind.

Dustin Watson has been skiing since he could walk. While a toddler’s first steps are an accomplishment enough for some parents, Watson’s parents took it as a sign he was ready to learn how to pizza down a bunny hill.

His early skiing background foreshadowed his future. He’s been working at the Glacier ski shop since 2014 and when he’s not in the shop, he’s usually in the ski area looking for fresh, untouched snow, and lots of it.

In 2012 the search for deep snow led Watson from “best run ever, let’s do it again,” to darkness.

On Dec. 7, 2012 the snow was deep; 41 inches had accumulated over the past six days and 21 inches had fallen that day to top it off. Watson and two friends headed up chair 6 for their second lap of the day on a run locals refer to as “sticky trees.”

The first run was even better than a “best run ever” as Watson often refers to them. They were skiing fresh powder through trees. The run was roughly 100 yards from chair 6 and separated by one ridgeline. The friends were on a race to get back up for another run, all while being hidden from the eyesight of the chair.

The world felt quieter than it ever had.

Days filled with hidden powder stashes at Mount Baker are plentiful, but burials and oxygen deprivation are also all too common. Watson passed his friends on the slope and went off a jump they’d seen the run before. Then the unstable snow revealed barely covered trees. He was sent flying head first into a tree well.

“There was a split second where I could see the light from the hole that I’d fallen into, but that was quickly covered and instantly it went totally dark,” Watson said.

Watson was trapped and hidden, roughly 50 feet from the track people traverse to get back to the main run.

“You need to be able to react in a split second and that ability can very well be the difference between life or death,” Watson said.

Watson often wears his backcountry gear inbounds because he was aware of the dangers well before getting buried, but safety tools are no help if nobody sees you go down.

The world felt quieter than it ever had. His muffled screams seemed to not even reach the surface. The snow began to feel like cement and with his skis and poles still attached, even wiggling felt impossible. Amid the disorientation, he realized which way was up, because his screams for help resulted in spit flowing onto his goggles.

It only took a couple screams to realize nobody would hear and it was just oxygen wasted in fear. Try to stay calm.

After 10 seconds, Watson realized he wasn’t getting himself out of this one. Statistically, the oxygen around someone buried in the snow runs out quickly and survival rates drop drastically after 10 minutes.

“It’s still blurry to this day,” Watson said.

Somehow, he emerged from his burial– after years of contemplation, he thinks someone saw one of his skis poking out of the snow and unearthed him. He never saw his savior. While in his near-death stupor, he might have told them he’d just fallen over and was fine out of shock, so they left. What else would make sense?

Watson said it felt like being dehydrated, standing up too quickly and visually blacking out, but for what felt like 20 minutes after he was unearthed. The light hurt his eyes and the ears of his frozen body rang, then he slowly realized what was snow and what wasn’t, and eventually, he was able to make out shapes.

When he came to his senses, he was hunched over next to the tree well with his gear around him, like a poorly organized yard sale.

Not everyone is as lucky as Watson to escape with their lives. Despite ski resorts across the nation closing prematurely due to coronavirus, this year’s ski season had a total of 23 estimated fatalities including skiers, snowboarders, snowmobilers and snowshoers, with four of the deaths inbounds of a ski area.

Washington holds the record for the deadliest avalanche in the history of the U.S. On March 1, 1910, an avalanche hurled a train off the tracks killing 96 passengers near Stevens Pass. Now, Washington has the fifth highest fatality occurrence from avalanches in the U.S. with an average of 2.5 deaths a year in the last 30 years, according to the Northwest Avalanche Center (NWAC).

NWAC is a center of over 20 people working to provide daily forecasts on avalanche dangers for the Cascade Range, from Canada to Oregon. Jeff Hambelton, NWAC snowmobile education coordinator, previously worked as a professional observer and as an avalanche control technician for Mount Baker. Having graduated from Western in December 1998 with an outdoor recreation degree, Hambelton wasted no time diving into a snow-filled career.

“Why do avalanches matter? Because we lose friends and family who are recreating,” Hambelton said.

Knowing the risks is not enough to keep people safe. Ventures into the backcountry are growing because of improvements in technology, loosening regulations on access to backcountry terrain and snow media’s focus on deep snow.

“Avalanche accidents are caused by humans making choices about what terrain they want to be in,” Hambelton said. “The problem is where we choose to put ourselves, and the solution has many folds.”

Avalanche fatalities often share common themes because the forces of nature and gravity are unchanging; it’s only the locations, names of victims and mourners who change.

Adam Ü is a professional skier and has mastered slopes across the world in places like France and Japan. During the winter months, he lives in Glacier, Washington, the last town before highway 542 ends at Mount Baker. The 41-year-old has been skiing at Mount Baker since he began his geography degree at Western in 1999.

“That’s the whole thing about mountains, is that if you’re out there long enough someone you know, or hopefully not yourself, is going to get hurt and someone is going to get killed,” Ü said. “You just play those number games long enough and you’re going to not come out on top every time.”

Backcountry skiing is the same sport but far removed from skiing inbounds at a ski area where dangers are mitigated by ski patrollers who will come to your aid if something goes wrong. It’s a totally different mentality from skiing in bounds when you are managing your own risks, and possibly paying the price for mistakes on your own, Ü said.

“At the end of the day when you’re in those extreme environments, there is an inherent risk by just being in that location and all the good decision making in the world is not more powerful than what the mountain will do to you,” Watson said. “People think ski patrol works every day to make the mountain as safe as possible and they’re right, but that’s what it is — as safe as possible. A small dedicated team can’t go out and mitigate and remove every hazard.”

Operating in an environment filled with risks that demand careful calculation transforms a person’s outlook on not only skiing but the world around them too. However, brushes with a snow-filled coffin and deaths of friends and family often aren’t enough to keep passionate mountain-goers away, nor is the knowledge of these events enough to discourage newcomers.

“Anybody who has experienced an avalanche in their community understands the devastating effects of losing a friend, family member or somebody that you know through recreation,” Hambelton said.

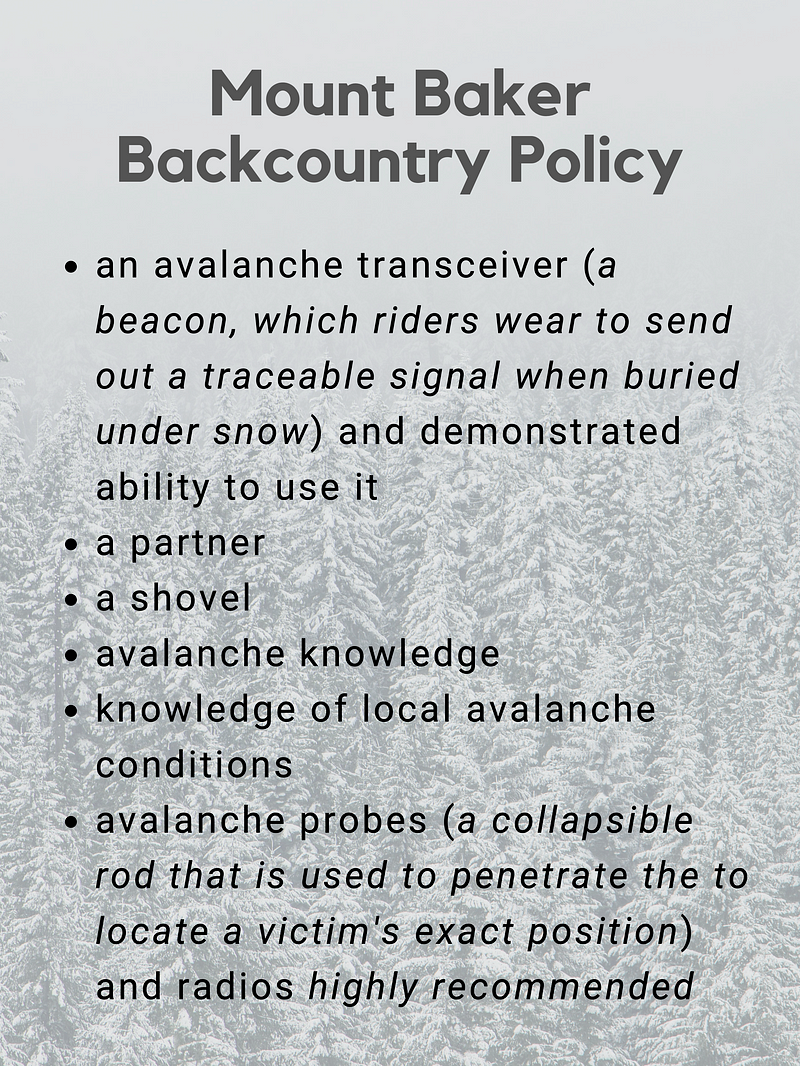

The Mount Baker Ski Area is a world-renowned destination. It attracts professional athletes from around the world in pursuit of powdery snow and challenging terrain. The ski area holds the highest average of seasonal snowfall of any ski resort in the world and operates with one of the most liberal backcountry policies in the nation.

“One of the most remarkable things about the backcountry policy at Mount Baker is how unique it is to the avalanche community in the rest of the United States,” Hambelton said. “They really have a clear-cut policy about who is in charge of whose risk and that rope line is the definition.”

Mount Baker’s system is far different from the constraints of other ski areas that require the use of specific backcountry access gates, which they control accessibility to with steep fines and possibilities for life long bans from the area for disobeying closures.

“Buying a transceiver isn’t like buying a lift ticket that gets you access somewhere,” Ü said. “It’s a body recovery tool, that’s for when it’s already all gone super sideways and you’ve already made horrible mistakes all along the way.”

Just because someone has the appropriate gear doesn’t mean they’re prepared and knowledgeable on using it for rescue when the situation is life or death and advancements in equipment across the industry have enabled people to travel further into the backcountry with more confidence.

“It’s obvious that backcountry use is getting more popular […] and the overall perception that they can manage avalanche risk has grown impressively,” Hambelton said.

Because of the rise in people accessing the backcountry and the inherent dangers, the U.S. Forest Service has partnered with NWAC and 13 other avalanche centers to ensure their message of the always-changing dangers of the mountains is heard.

“It’s one of the largest geographic responsibilities for any avalanche center in the country,” Hambelton said of NWAC.

Most people go through a stage when they’re young and feel invincible in the mountains, Ü said.

Even experienced riders are susceptible to tragedy because they operate in terrain where safety isn’t guaranteed and anything can go wrong. Ü can think of three close calls, despite decades of experience.

“Looking back I can see everywhere I messed up, but that’s the thing is that if you’re out there for long enough, you’ll eventually let your guard down for whatever reasons or number of reasons. No one is immune to this,” Ü said.

Backcountry travel is filled with natural traps, but psychological traps can lead skiers to danger.

“Most people underestimate that connection [between snow science and human psychology] and don’t see it as an equal part to the process,” Hambelton said of an avalanche education course. “They want the solution to come from snow and they’re surprised we are going to spend so much time talking about psychology. People come away from an avalanche course reflective and kind of changed.”

In a study by Diana Ilona Patricia Saly, a camera was set to track movements of riders in a backcountry zone neighboring a ski area. The data was then analyzed to see if riders choose less avalanche prone terrain when avalanche danger is high.

“We found that terrain choices are statistically different with different avalanche hazard[s], even in terrain with limited options,” Saly wrote. “In general, skiers chose more conservative terrain as avalanche hazard increased. Surprisingly, we also noted a high percentage of solo skiers indicating a need for further research and education on backcountry group size and skiing with a partner competent in self-rescue.”

People will never understand why mountain-goers would put themselves in a position of risk unless they’re a part of it themselves, Ü said.

“If I’m going out with you, we might not be saying it every time we go out, but I’m putting my life in your hands,” Watson said. “If something happens, I need to trust that you can get me out of the situation and vice versa.”

Planning, analyzing, reanalyzing, communicating and operating safely all become a way of life that crosses over beyond backcountry travel when practiced enough.

“It’s one of those things where once you start thinking about hazards and consequences it permeates everything you do and how you think about everything,” Hambelton said.

Despite the risks and close calls, skiers like Watson don’t let narrow escapes slow them down.

“I didn’t feel deterred or defeated necessarily because I know that experience could happen to literally anybody. There is no amount of skill that can mitigate the risk of the unknown,” Watson said. “You have a lifeline but never a guarantee of safety.”

To this day Watson still can’t put the pieces together. Because of oxygen deprivation, he doesn’t know how he got out of his burial or who might have come to his rescue.

“If someone is reading this article down the road and remembers the scenario from 2012, reach out to me,” Watson said. “I would love to buy you a beer and thank you in person because whoever saved my life, I have no idea who they were.”

This year, Watson was nearing the summit of Coleman Pinnacle on Ptarmigan Ridge with two friends when they looked down to see what they thought were elk tracks. It turned out to be a pack of grey wolves. Watson and his crew had multiple standoffs with the pack of eight or nine while trying to retreat to their car. Eventually the wolves turned around after the skiers descended a large slope. Eight years after the burial, Watson is still experiencing the unpredictable risks of the mountains.

Having these ‘oh shit’ moments make you operate in the world differently when the ultimate price to pay is your life. Historically and statistically, there is no sign of fatalities in the mountains slowing down.

“It reaffirmed to me that the risk-to-reward of that way of living is totally worth it to a certain level. I feel pretty confident that I can live my life and still do this while operating safely,” Watson said.