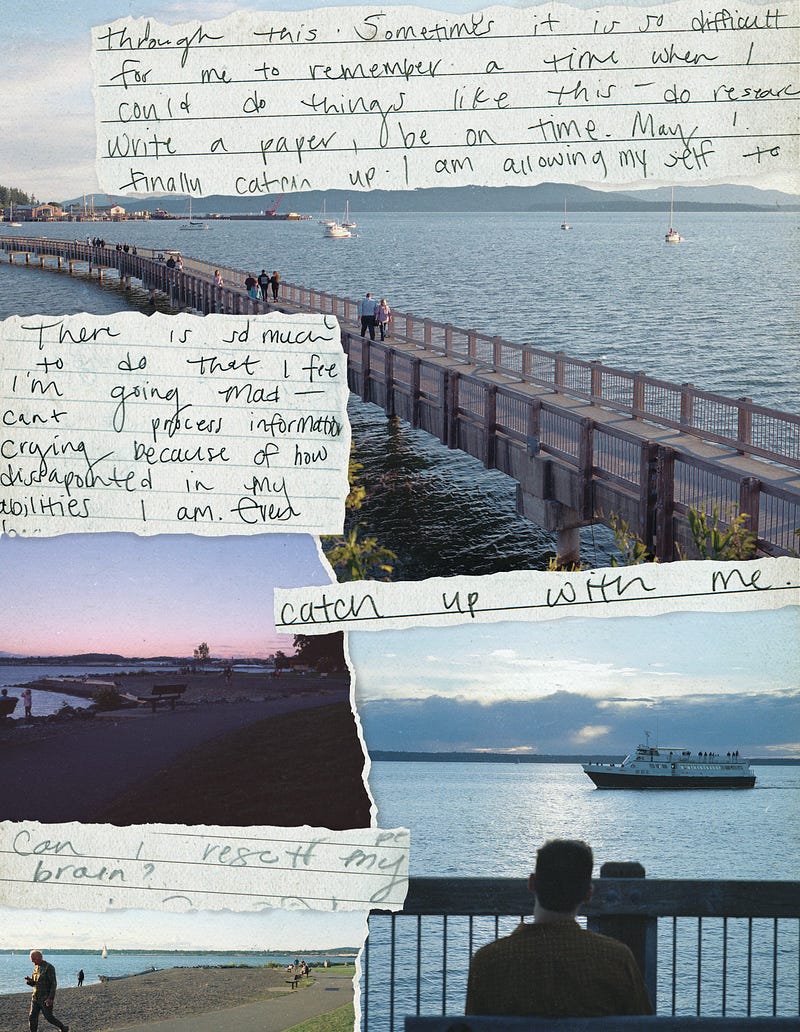

Playing Catch Up

Being diagnosed with ADHD in your 20s.

Story by Alisha Dixon

M y fists clench the canvas material of the pillow I have sitting in my lap, an anxious habit that helps me stay grounded. I’m staring blankly at my laptop while my brain works hard to solve what’s on the screen: a variety of shapes — all different sizes and patterns facing different directions. Like pieces of a puzzle, a few of the shapes are supposed to fit together to create a larger picture.

“I’m sorry. I don’t know. I can’t do this one,” I say.

“That’s alright. We’ll go to the next,” the psychologist replies in a soft voice. Through the computer screen, I see her jot down notes before moving on to the next question.

I can’t help but feel like I’m failing a test. She lists out 20 words to me and I’m supposed to recite them backwards, but I only remember six. For the next hour, I struggle through similar exercises, each one more difficult than the next.

I’m wondering how there are people who can complete these problems without crying.

Two weeks later, an email from the psychologist pops up in my overcrowded inbox. Attached is a 10-page report on how my brain works. To sum it up, my executive function doesn’t work the way it’s supposed to. I look at the screen, anxious yet relieved as the answer to so many questions I have about myself sits in front of me.

I have ADHD.

ADDitude Magazine, a popular resource for families and adults in the ADHD community, explains executive dysfunction as “brain-based impairment that causes problems with analyzing, planning, organizing, scheduling and completing tasks at all — or on deadline.”

These functions allow individuals to act in goal-oriented ways, meaning their decisions and actions are steps toward something they want to accomplish long-term. The neurotransmitter dopamine, which controls pleasure and reward, can play a part in ADHD. Studies have shown that levels of dopamine are different between people with ADHD and people without.

Looking back, it’s easy for me to see that I experience many of the common ADHD symptoms, but I always wrote them off as circumstantial or a symptom of another mental illness. Symptoms like disorganization, poor focus and difficulties with sensory processing are seen in people with ADHD as well as other neurodiverse people.

I was already diagnosed with depression, anxiety and PTSD, so I assumed my lack of attention and motivation was because I was depressed. I spent middle and high school struggling with my mental health, but was able to get by in my classes because I loved learning. I had structural support and parents who made sure I finished my homework.

However, things changed when I graduated and went to college.

Moving to Bellingham, Washington and beginning my studies at Western Washington University was like getting thrown into the deep end of a pool. I dog-paddled through my freshman and sophomore year, staying just above water.

In my third year of university, pre-ADHD diagnosis, my symptoms became impossible to manage. I was overwhelmed with schoolwork as my classes got harder. I couldn’t focus, had trouble keeping track of deadlines and didn’t recall much of what I learned.

Going through the motions just to get by took everything in me. Self-doubt became crippling and I truly believed my brain wasn’t capable of being in school.

I should just drop out. I’m not cut out for this. It felt like I was always playing catch up with my peers in a constant loop of comparison and shame. I was prescribed antidepressants that did more harm than good and had to withdraw from classes.

Dropping my classes to protect my mental health seemed like the best choice. I tried new medications, set myself up for success by preparing for the upcoming quarter and practiced good study habits.

Maybe I can get my brain to work for me this time.

The beginning of the quarter always starts out on a high. I’m finally going to be successful! I’m excited for my classes and I’m learning about the things I love! But I know now that my brain lacks the chemicals I need to feel motivated and make these things happen, regardless of how much I want to do them. Watching a YouTube video on productivity or trying the routines of the most successful people in the world don’t give me the dopamine to harness the motivation I desperately need.

When COVID-19 hit and universities moved to virtual meetings, I didn’t even think about the mental impact of learning without a classroom.

I fidget with whatever I can reach; I lock and unlock my phone for the small rush of dopamine that can get me through the rest of a professor’s presentation.

I make my way to the kitchen, laptop in hand to make another cup of coffee that will make my heart race for the rest of the day, but at least I might get an assignment turned in.

Though struggling through virtual classes has taken a toll on me, it also gave me the push I needed to look into an ADHD diagnosis. Rates of ADHD in college students are estimated to be around 5%, and 25% among students with disabilities.

My experience getting diagnosed leaves me hopeful for others who were given different diagnoses as children. Women are especially likely to be misdiagnosed, or have their symptoms overlooked. My late diagnosis is not uncommon, since young girls often don’t present “traditional” ADHD symptoms. This is changing, however, as more research and education about ADHD is becoming more available to the public.

Growing up wondering why your brain doesn’t work like everyone else’s is painful and self-advocating as an adult can be even harder. Humans are learning more and more about ADHD and mental health symptoms, validating the experiences of those who are struggling. I’m hopeful for a world where students can learn in the ways that best work for them, regardless of what they want to learn.

I roll out of bed, my feet bracing the cold floor to make my way to the bathroom. I take my stimulant medication with a glass of water. It’s not a fix-all, but I’m able to sit through my Zoom class.

Having an ADHD diagnosis gives me peace of mind. It takes away some of the guilt I have about how my brain functions. I know now there are forms of learning that can work for me, medications that help and an entire community of people experiencing the same things. I’m still learning and adapting, but I’m closer to catching up.