Detached

How isolation affects our capacity for empathy.

Story by Garrett Rahn

There’s a small crack between the thin wooden squares above my bed. I’m trying to decide how I feel about that.

I’m not really sure how I feel about anything.

My eyes drift across my cluttered room in response to a buzz and faint blue glow from my phone, which illuminates this shadowy space much more than I would have expected.

When did it get so dark? How long have I been lying here?

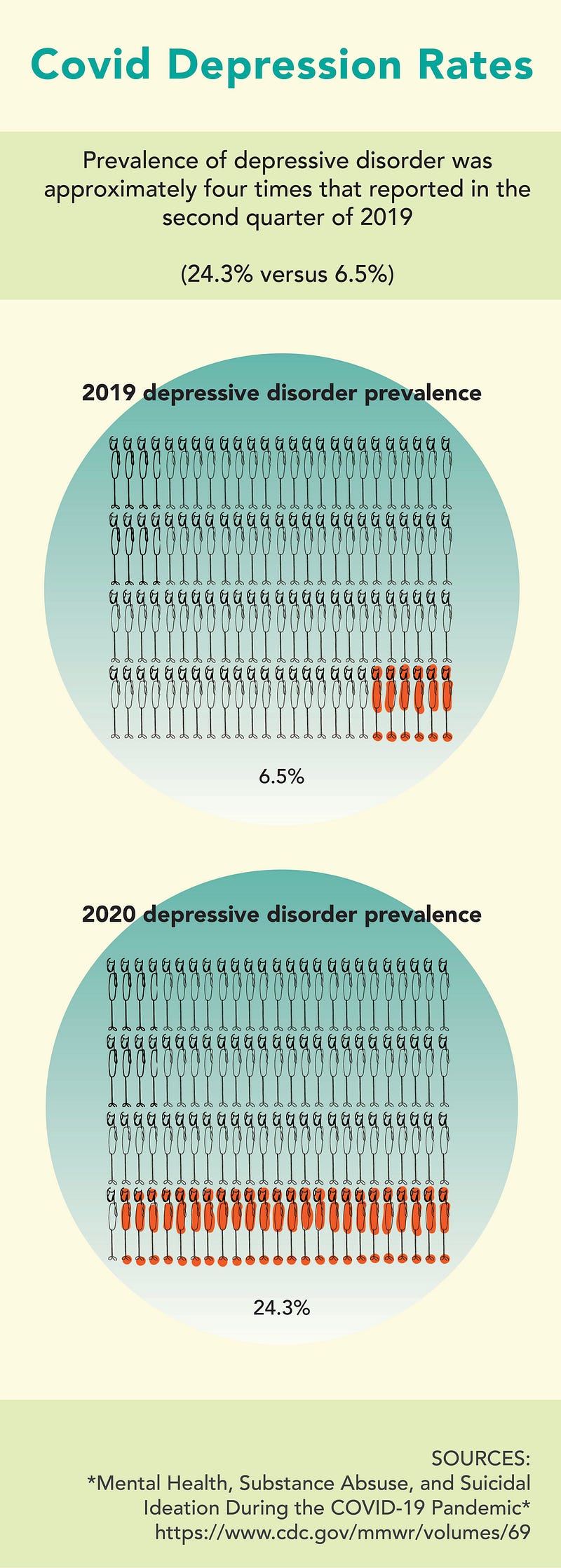

Before the lockdowns, I had my chronic depression under control. But since the beginning of the pandemic, I have experienced an increase in depressive episodes. I’m not the only one — according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in 2020, four times as many U.S. adults reported having a depressive disorder than in 2019.

Businesses closing, social distancing measures and government stay-at-home orders have forced us to be alone a lot more than we are used to, leaving many of us feeling isolated.

“Isolation is more than just being alone, because you can be alone and be good,” said Dr. Sislena Ledbetter, Executive Director of Counseling, Health and Wellness at Western Washington University. “But isolation feels like something else, it is being alone and feeling lonely.”

And that loneliness is where the trouble begins. Research has shown that not only does loneliness cause depression, but it also vastly increases the risk of premature death. But how does it affect our capacity for empathy?

According to research done in 2018, there are two different types of empathy: cognitive and affective. Cognitive empathy is the ability to take on the perspective of another human being, and affective is the ability to actually share their emotions. An experiment done in November of 2020 found that depression can greatly diminish affective empathy, but has little to no effect on cognitive empathy.

When I am in one of these episodes, it’s as if my mind ices over, numbing me to my emotions, leaving my perception of the world dull, grey, bland. As a result, affectively empathizing with other people becomes borderline impossible. After all, how can you take on the emotional experience of another when you’re unable to experience emotion?

This doesn’t mean that I can’t understand someone else’s perspective with cognitive empathy. But relating to people across the aisle demands a two-pronged empathetic approach. Without it, I have seen in myself an unsettling shift away from compassion towards vitriolic partisanship.

A good example of this is my reaction toward the people who refuse to wear masks, despite their proven effectiveness, or those who protested to open the state’s economy again when the governor locked everything down. At the beginning of the pandemic, I understood their frustrations. A lot of people I knew lost their jobs, and it was really unusual to wear masks everywhere. I didn’t necessarily agree with what they were saying, but I didn’t hate them for their stance.

Fast forward a few months, and my entire attitude flipped. I’m buying groceries with my partner at Target, and I end up yelling at a maskless stranger, hating him with my entire being. I was unable to stop myself and consider how he might be feeling, or that there may be a better way of getting through to him.

And it’s only getting worse.

This issue of isolation and decreasing empathy is a positive feedback loop, feeding into itself and further exacerbating the problem.

In my experience, being depressed and unempathetic leads to further isolation, and thus aggravated depression.

If so many of us are feeling as though our ability to connect and grow has been diminished, then it comes as no surprise that its effects seem to have rippled out into society, the economy and our political culture, further widening harsh divisions.

So what can we do? How do we regain our empathy at a time like this?

There are a few options, and from what I have tried, they seem to be working.

First, we must reestablish social connections through whatever means possible. “We are hardwired to connect with people, and that has been disrupted,” Ledbetter said. “In the past, when we ran into people on the yard or on campus, it was organic — we didn’t schedule meetings. Now that we don’t have that, it might not be a bad idea to schedule times.”

I have done my best to follow this advice. I’m reaching out to old friends for social distanced coffee, creating Discord groups and making regular contact with my siblings.

Next, we have to practice self-care by doing things for ourselves.

Self-care can mean any number of activities, from cleaning your room and doing a facemask to making an appointment for talk therapy. WWU students have the option for free therapy sessions with licensed counselors, like Ledbetter, through the Counseling Center.

Finally, it has been shown that a great way to help yourself is to help others. A number of studies have found that doing compassionate acts for other people can function as a treatment for depression and increase empathy. Compliment that stranger on their jacket, donate to your community’s mutual aid, give some brownies to your neighbor — the smallest things can make all the difference.

“I think we have to be caring, thoughtful and acknowledge that this has been tough for everybody,” Ledbetter said.

I know that there’s no way to completely fix the situation we are in right now. But maybe we can make the circumstances a little better for ourselves and others, and little by little, we’ll make it out of this alright.