Photojournalism Needs a Reckoning in Consent

The history and ethics of consent in photojournalism should be addressed and changed.

Story and photos by Oliver Hamlin

I n my first week at my new job as a photographer for a newspaper, I had a lot on my mind. It was the summer of 2020, and there were a lot of conversations going on about how photojournalists should act at protests and the harm they can cause by taking pictures.

I worried that I would be someone with good intentions but would ultimately do more harm than good while photographing a protest. I had to reckon with these thoughts quickly, because during my first week on the job, I was assigned to photograph a Black Lives Matter protest in Burlington, Washington.

When I arrived at the protest, crowds were lining either side of Burlington Boulevard with signs as cars drove on the busy road. A base level of agitation was present as some drivers and protesters exchanged concerned looks and a couple of men with large guns watched from a distance.

While most stayed on the sidewalk, a few individuals kneeled in the middle of the street with their signs. I knew that photos of the people standing out of the crowd would make them easily identifiable without masks.

I wondered what they would think if they saw their picture on the front page of the newspaper the next day.

I published a number of photos of the kneeling demonstrators. One showed the back of a young man’s head who I could not find after the demonstration. Another showed a man with a mask, sunglasses and a hood. The third person in the photo was clearly identifiable, but I found him after the protest and he agreed to give his name.

In many cases, the easiest solution to photographing people in public spaces is going up and talking to them.

In 2020, a much-needed debate on the ethics of consent in photojournalism arose in the community. Some people advocated for the blurring of faces in photos that were taken at Black Lives Matter protests in response to the killing of George Floyd.

While the manipulation of photos has almost no place in photojournalism, it does bring into question what it means to get consent from the person being photographed.

As a photojournalist at the Skagit Valley Herald, I often think about the nuances regarding what it means to get consent from a person, along with how my actions can affect someone’s life. I had been taught that as long as I’m in a public space, I can photograph whoever I want. However, this attitude can sometimes do more harm than good.

The National Press Photographers Association’s code of ethics states, “Give special consideration to vulnerable subjects and compassion to victims of crime or tragedy. Intrude on private moments of grief only when the public has an overriding and justifiable need to see.”

This statement is not followed enough.

Photojournalism took off in the early 20th century after the first commercially available 35 mm camera was released in 1925. This led to publications that heavily featured photojournalism, like Life magazine and the Farm Security Administration’s photography program.

While many photographers of this era were thoughtful about the way they treated others, the nuances of consent were rarely considered.

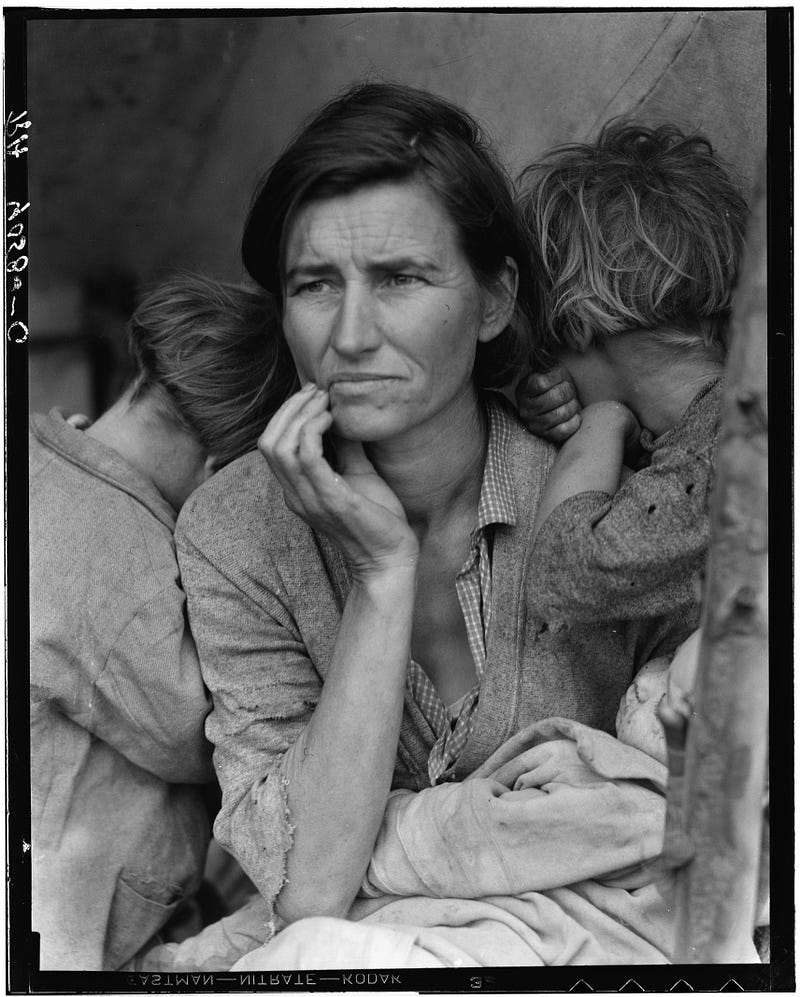

For example, the photo “Migrant Mother,” taken by Dorothea Lange during the Great Depression in 1936, portrays a mother, Florence Owens Thompson, looking longingly with a hand to her face as two of her children hide their faces behind her. In an interview with Thompson decades later, she describes an encounter where Lange asked her age but did not bother to ask her name or any other details about her life.

“I wish she hadn’t taken my picture,” Thompson said. “I can’t get a penny out of it. She didn’t ask my name. She said she wouldn’t sell the pictures. She said she’d send me a copy. She never did.”

While Thompson may not have explicitly said “no” to being photographed, she did not give consent because she was deceived by Lange. Not only was it in poor taste to treat a person that way, but it was bad journalistic practice, because Lange did not get the correct information and published the photo without proper context.

It is important to differentiate between photos that could be taken and those that have to be taken. There are times when a photojournalist captures an event with such historical significance that the need to document outweighs the consequences of it being published. However, regardless of the situation, the photographer should always make intentions clear and contextualize the photo.

The actions taken by famous photographers like Lange and the impacts they had on the people they photographed can be applied to modern photojournalism.

In 2020, a group called The Authority Collective published a guide on ethical practices regarding the visual coverage of protests. “To be a person ensconced in the protections of white privilege and/or masculinity as well as institutional support via mainstream news outlets is to never have to think about what might happen to people without those protections,” the guide says. “Black and brown protestors targeted by the police and others cannot call on such powerful entities to come to their aid once those same news outlets have published their identities, opening them up to arrest, doxxing or worse.”

In the digital age where photos can become viral quickly and the identities of the people in the photos can easily be discovered, it is important that a photojournalist takes into account the dangers that the photo can cause.

While people like Thompson could stay anonymous for decades when photos could only be seen in print, today a person subject to a famous photo will undoubtedly be identified. We now live in a time where police departments try to uncover unpublished photos to help in their investigations, which is not the job of a journalist.

Just as the technology in photojournalism and its reproduction has evolved, so should photojournalists.