Dream House

A look into the current state of the Bellingham, Wash. affordable housing crisis and how local groups are helping those in need.

Story by Shannon Steffens

Iris Dunaway and her family lived in a small two-story house that was falling apart — at over 100 years old, it was lacking both a foundation and insulation. Bellingham, Washington’s cold winters seeped through their walls, and a leak in the bathroom roof created a pool of icy water on the floor.

This wasn’t their dream home by any means; it was simply a house that had been in the family. But their plan to one day find new housing accelerated in 2012.

That year, their 5-year-old son was diagnosed with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a progressive muscle disease that will eventually require him to use a wheelchair. Dunaway and her husband, Solly Perry, quickly decided their deteriorating house would no longer meet their needs.

But the couple had no idea how difficult it would be to find a permanent house in the area, especially a three-bedroom, single-story they could afford as a one-income family.

It took seven years for Dunaway and her family to find an affordable house in Bellingham. They moved in just over a year ago, in December of 2019.

Their experience is not unique.

Bellingham is in the midst of an affordable housing crisis, and low- to moderate-income individuals and families like the Dunaway-Perrys are facing the brunt of it.

Current state of housing

From October 2020 to December 2020, the median home value in Whatcom County was $470,400.

It’s no wonder that 67% of families in the area can’t afford a median value home, especially when home prices are increasing much faster than wages. According to the City of Bellingham, the median home value increased by 67% from 2000–2017, while the median household income only increased by 15%.

This increase in housing prices is mainly due to high demand and low supply, and it doesn’t show any signs of stopping. Bellingham’s population grows by about 1,400 each year, and not enough housing is being built to make up for this increase.

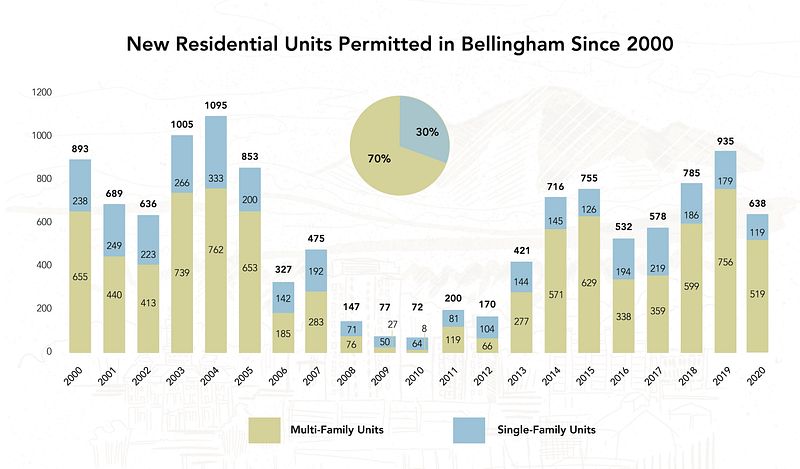

One reason the amount of available housing is so low is because of the Great Recession in 2008. As illustrated in the graph, compared to the years prior, there were very few new residential units built between 2008 and 2012.

As the population grew, it created a disparity between the number of people needing housing and the number of housing units available.

This impact is still seen today in Whatcom County’s low apartment vacancy rate of 0.5%. Compared to the “healthy” rate of about 5% of rental properties being vacant, this is a significant difference.

Because many families are unable to afford houses and there are so few rental properties available, the demand is causing rent prices to rise.

According to the renting website Zumper, from January 2017 to January 2021, the median one-bedroom apartment rent in Bellingham has increased by 23.7% and the median two-bedroom rent has increased by 14.3%.

Like home prices, rent is increasing much faster than wages.

Dunaway said it was immediately clear to her and her family that they wouldn’t be able to afford rentals with a singular income. No matter where they lived, they would need to modify the space to make it more accessible, and they would have no guarantee that the rental would remain theirs.

She put herself on a Bellingham Housing Authority waitlist and hoped they could help her family find somewhere affordable to live. Unfortunately, the list was long and it could be years before they heard anything back.

Brien Thane, executive director of the Bellingham Housing Authority, said that for many decades, families who made around 60%-100% of area median income could realistically think about buying their first home.

Thane said this is no longer the case. Nowadays, these families are stuck; they can’t afford to buy a home, but rising rent prices are taking more and more of their income.

In fact, one in four working Bellingham families can’t afford their basic needs, let alone afford to buy a house.

Thane said the affordable housing crisis affects everyone living in Bellingham, not only low-income individuals and families.

Upper-income families and businesses are also affected by the lack of housing because it depresses the labor market. Thane said it makes it difficult for companies to be able to recruit and retain a stable workforce when many have to move elsewhere to find affordable housing.

“The price of housing is very important to just about everyone,” said Chris D’Onofrio, housing specialist at Whatcom County’s Housing and Homeless Services Program. “For the vast majority of homeowners, that home is their single biggest asset in terms of personal wealth. As homes increase or decrease in value, it can change the financial outlook of an individual or family in really significant ways.”

Helping low-income families

The good news is that low- to moderate-income families don’t have to struggle to find housing alone.

Kulshan Community Land Trust is working to buy and build homes that will be permanently affordable for working families. Along with this, before the COVID-19 pandemic forced their office to close, they held financial and educational classes for people needing them.

The Dunaway-Perrys had looked into the land trust back in 2012, but the few houses available for their budget at the time were small and run-down. The family was losing hope. Would they be stuck in their current house forever? What would that mean for their son?

Luckily, in 2018, Kulshan Community Land Trust gained several properties from the Housing Authority, renewing the family’s hope for a new home. They immediately joined the waitlist and, because of their son’s more immediate needs, were moved up the list.

In 2019, the family secured their dream three-bedroom home at just $265,000. It wasn’t perfect; after being a rental through the Housing Authority for 30 years, the gray and blue house needed a new roof, new flooring and a new water heater. With the help of Kulshan Community Land Trust, a rehab loan through the City of Bellingham and their friends, the Dunaway-Perrys were able to fix up the house and move in December of that year.

With one ramp leading to their front door and another to their small garden, the house is much more accessible than their previous one.

“It’s amazing,” Dunaway said. “We couldn’t have done it without Kulshan, and now we own our own home. We have that housing security, we can afford it on one income and then we can have my husband home to care for our kids.”

But how does Kulshan Community Land Trust keep homes permanently affordable when prices are skyrocketing?

Dean Fearing, executive director of Kulshan Community Land Trust, said they create a 99-year ground lease every time somebody buys a home through them. Because they own the land underneath the home, they can ensure their homes stay affordable.

He said the housing market grew by 20% in 2020, while the land trust’s homes grew by just 1.5%. The homebuyers earn 1.5% per year in equity, and so if they want to one day sell the home, it will still be affordable to low- and moderate-income families.

Fearing said they help between 10 to 15 families a year. They’re planning to build about 70 homes in the next several years, and their goal is to help more and more families annually.

Typically, the land trust works with families making at or below 80% of area median income, which, for a family of four, is about $56,000 per year. But Fearing said home prices have risen so fast that families earning up to $80,000 per year (around 120% of area median income) are now priced out of homeownership.

Because of this, the land trust has changed the structure of their program to start helping families earning up to that higher income.

Recently, Kulshan Community Land Trust partnered with the Whatcom County Habitat for Humanity to build 54 two- to three-bedroom townhomes that will sell for $150,000 to $200,000. Eight have been built so far.

“This partnership has worked out really well for both organizations, because it helps us serve a more diverse range of home buyers,” Fearing said. “It allows both organizations to help more families than we’d normally be able to on our own.”

Fearing said, ideally, half of the homes in Bellingham would be priced below the area median income and half would be above. He said the number of people severely cost-burdened by their housing and homes is significant.

Homelessness

With both apartments and homes growing more unaffordable, and with a full-time minimum-wage worker only making about $28,000 a year, many people have been left without permanent shelter.

In 2020, Whatcom County had at least 707 people who were homeless. Of the 555 homeless households (defined as one or more people in a group), 36% reported being homeless for 12 months or more.

While Gov. Inslee’s eviction moratorium has kept individuals and families financially impacted by the pandemic in their rentals, the March 31, 2021 expiration date is getting closer every day.

“When the ban expires, I suspect we’re going to see more people becoming newly homeless,” said Doug Gustafson, co-founder of the nonprofit HomesNOW! Not Later. “We have to get ahead of the curve now; it’s kind of like we’re practicing right now for what’s going to be a bigger problem later.”

About 100 people without shelter were forced to leave their homeless encampment, known as Camp 210, outside of City Hall on Jan. 28, 2021. This camp had been up since November 2020.

Mayor Seth Fleetwood ordered this camp to be dismantled due to increases of violence and public health risks around the area. With nowhere to go, many people from the camp moved across Interstate 5 to an area outside of North Coast Gymnastics Academy. On March 2, 2021, a man who had been staying at the camp was arrested for assaulting an 11-year-old girl as she left her gymnastics class.

Gustafson said he helped 22 people originally camping at Camp 210 move into HomesNOW!’s latest project, Swift Haven, in January. This is a village of tiny homes that people in need can live in until they find more permanent housing.

This is the second tiny home community built by HomesNOW! and was quickly opened in early January as a temporary winter shelter. Their first tiny home community, Unity Village, has been running since September 2019.

Gustafson said about 45% of people the nonprofit helps get off the streets find permanent housing after their stay in a tiny home.

With the current circumstances and the impending eviction moratorium expiry date, HomesNOW! has been looking into setting up a third village for those in need.

Where do we go from here?

By working in affordable housing for over 30 years, Thane has an informed perspective on the future of this housing crisis.

“I think it’s going to take a long time for [the affordable housing crisis] to get better,” Thane said. “But I’m pretty hopeful, because I think more and more people are aware and are getting a better understanding of some of the challenges that have created this situation.”

The City of Bellingham has been focusing on the issue of affordable housing and homelessness and spends about $5 million annually for services and housing contracts. They are also working to quicken their residential permit process.

The Home Fund levy passed in 2012 and 2018 is also helping by funding the creation and maintenance of hundreds of rental and transitional housing and providing rental assistance to people in need.

In the long term, the hope is that the vacancy rate rises and we can get to a point where the amount of housing increases at the same rate the population increases.

But for now, Bellingham families are struggling.

After all this time, Dunaway feels a sense of relief. She’s grateful that her family qualified for Kulshan Community Land Trust’s help and that they were able to find permanent housing before the pandemic began. But she is all too familiar with the difficulties of the families getting left behind.

Two of her friends are full-time teachers who have been renting for years and are still unable to afford a house in Bellingham.

“The availability of affordable housing is just so limited,” Dunaway said. “We have to make it a priority as a community to support places like Kulshan Community Land Trust and other ways that families can afford to live here and do important work.”

Until that becomes a priority, it’s difficult to see an end in sight.