Bottle to Throttle

Two Veterans’ stories reveal how the military’s structure can lead to addiction and recovery.

Story by Michelle McDaniel

It’s 2011. I’m 20 years old, unqualified and on my first deployment in the Navy. My crew and I are on a detachment in Pattaya Beach, Thailand, where the legal drinking age is 20. I think it’s cool that I get to celebrate my 21st birthday a year early in a tropical paradise.

One night, we’re all drinking at the beachside hotel’s bar. Our captain raises his glass, cheers us and we shotgun our drinks, seconds before our cut-off time. In Navy terms, this is the bottle to throttle rule, meaning that aircrew members must stop drinking alcohol 12 hours prior to flight duty.

During preflight the next morning, I inspect the oxygen tank at my station. After tightening the mask over my face to ensure a proper fit, I do something that’s not in the routine. I crank up the oxygen and suck it down, because someone told me that this was a good way to cure a hangover.

Even though I drank on occasion in the Navy, I never became an addict. However, the drinking habits of others led to much different outcomes.

Addiction is prevalent in the military and can be attributed to the military’s structure itself, which promotes binge drinking, a form of alcoholism. A research study at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism shows how “the easy availability of alcohol, ritualized drinking opportunities and inconsistent policies contribute to a work culture that facilitates heavy and binge drinking in this [military] population.”

Dr. Noel Elrod is the addiction treatment program team lead and staff psychologist at the Harry S. Truman Memorial Veterans’ Hospital in Columbia, Missouri. According to Elrod, there’s no one cause that leads to addiction. Instead, it’s a culmination of different kinds of risk factors like having a genetic predisposition, a family history of addiction or having experienced traumatic events in one’s life that all lead to a “perfect storm.”

The following stories are about two Navy Veterans, one retired and the other honorably discharged. Although I am a Navy Veteran myself, these two individuals were never in my command, nor did we fly together. They are simply my acquaintances, sharing their stories with me.

Zach’s Story

Since 2018, Zach, a retired Navy Chief Petty Officer, has been spending more time with his kids and working toward a dual bachelor’s degree in human services and business administration. He’s grown out both his hair and beard past his shoulders.

In his house on Whidbey Island, Washington, sitting beside bookshelves filled with houseplants, books and a pink himalayan salt lamp, Zach talked to me about his first experience with alcohol in the Navy, beginning the night before boot camp.

He was underage while sneaking beers with his recruiter at a military entrance processing station.

“I thought this was normal,” he said, shrugging and looking away. “My recruiter was showing me how awesome the Navy was going to be.”

Zach spent the majority of his naval career breaking curfews and drinking nonstop. He said that his drinking was at its worst while on deployments overseas. Coughing fits led to vomiting, occurring every morning before work.

It wasn’t until “almost dying from a hangover twice in one day” that he realized he had a drinking problem.

Zach attempted suicide and didn’t show up to work for several days because he slipped into an alcohol-induced coma. Personnel from Zach’s command found him in his home, on the verge of having a stroke.

“My blood pressure was 220/60,” Zach said. “At 10:30 a.m., my blood alcohol level was .367 BAC. Later on that day, it had risen to .4 BAC.”

Zach was then hospitalized for 48 days at a rehabilitation center near Seattle, Washington. Although he was unable to have contact with his friends and family, Zach said he loved rehab.

“I needed to be broken,” he said.

Ryne’s Story

Since Ryne was honorably discharged from the Navy in 2015, he’s earned his master’s degree in philosophy, backpacked the Appalachian Trail, bike-toured the Pacific Coast and thru-hiked the Colorado Trail. He’s now working on building his social media and digital content brand.

Sitting on a brown-leather couch inside his home in Denver, Colorado, the wall behind Ryne is covered with trail maps from his backpacking trips. He, too, shared with me his first experiences with alcohol in the Navy.

The 60 days that Ryne spent in boot camp was the longest he’d gone without drinking alcohol since his early teenage years.

Three days into boot camp, Ryne stood at attention at the foot of his bunk bed shaking and sweating, experiencing physiological effects of delirium tremens, which can occur when someone is severely withdrawing from alcohol.

For unknown reasons, Ryne was put on a temporary hold in Great Lakes, Illinois after boot camp graduation. Boredom set in from dealing with the frustration of not knowing why he was there, impacted by the uncertainty that loomed over his naval career.

Ryne started sneaking beers into his locker and secretly got drunk in his open barracks room. In a strict setting like boot camp with rules such as a no alcohol policy, one can assume that alcohol will be involved, Ryne said.

Three months later, Ryne transferred to Pensacola, Florida from boot camp. Earning off-duty liberty was like coming of age, he said. He recalls the time he spent at his training command in Florida his dark years. One weekend, he was picked up by Pensacola Beach lifeguards and wondered how his command never found out.

Later, at Ryne’s training command in Jacksonville, Florida, he had a difficult time honoring the bottle to throttle rule.

“If I was passing school, it was OK,” Ryne said he figured, but his command became suspicious of his drinking problem.

Ryne was given an ultimatum from the Navy that he had to stay sober for three years and go to intensive outpatient rehabilitation therapy. He said that before rehab, he’d never heard someone tell him that he was lucky to be alive.

Less than a year after rehab on Ryne’s first deployment to Bahrain, the tactical officer of his crew caused a scene by making him take a beer card against his will. Beer cards allowed military personnel to have three beers a day. When Ryne refused to take the card in front of his crew, his tactical officer asked what was wrong with him.

Reluctantly, he took the card, only to tear it up in privacy shortly after.

Championship Of Recovery

According to the National Center for Biotechnology Information, “among treated individuals, short-term remission rates vary between 20% and 50%, depending on the severity of the disorder and the criteria for remission.”

Zach has been sober for four years now and Ryne has been sober for 10.

Sobriety is living the exact same life as before minus the alcohol. But recovery, Elrod said, is “engaging in a life that’s so enjoyable and meaningful for you that you don’t even want to use the drugs or alcohol.”

“Addiction is not a moral failing or a choice that people make, it’s a chronic disease,” she said.

According to Elrod, one of the biggest barriers that addicts face is the stigma that comes from other people judging them for their fight with addiction. They also have difficulty asking for help, leaving them feeling like they should be able to handle it on their own.

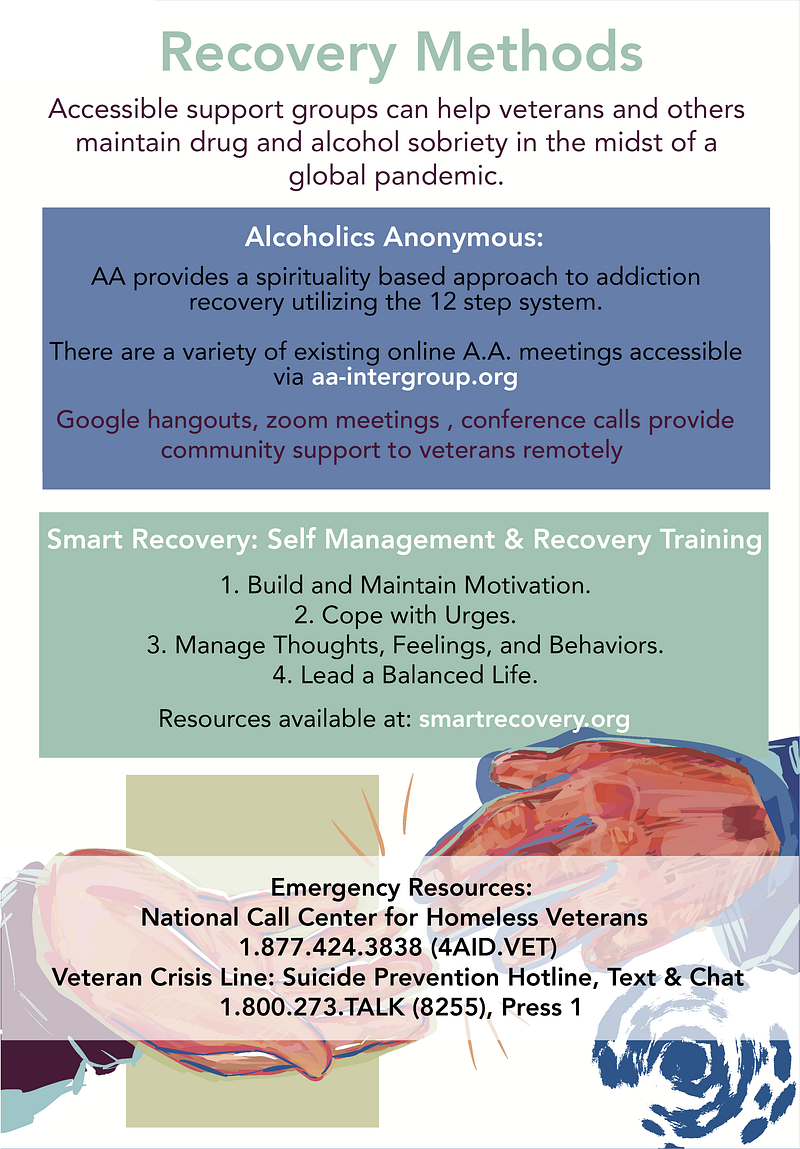

Zach’s sobriety since rehab is aided by the support of his friends and family, along with an online support group called Self-Management And Recovery Training (SMART), which has been helpful during the pandemic.

His championship of recovery was learning to be empathetic toward himself, which has allowed him to cry over beautiful things like birds in his yard and vulnerable moments in movies.

On the other hand, Ryne misses in-person support group meetings because they make him feel more connected with other people facing alcohol addiction.

Talking about his addiction keeps it fresh in his mind and encourages him to accept himself. Ryne has been sober since rehab in 2011 and says he’d “rather play with a loaded handgun than drink.”

The tools of recovery are applicable to anyone going through something difficult if they’re willing to listen and express real honesty, Ryne said.

I was honored that these two strong Veterans felt comfortable enough to open up and talk to me about their struggles. I never thought it was possible that the same structure of the military that led them to addiction could also save their lives. I want to thank Zach and Ryne for having the courage to be a voice for Veterans and sharing their stories of addiction, because they are not heard enough.

“This is not the end of your recovery, this is your beginning and has been like your spring training,” Elrod said. “You’ve been taught some skills and have worked on your technique. Now, you get to go out and play in the major leagues.”