Expired

The risks and benefits of eating past the expiration date

STORY BY MIKEY JANE MORAN

photos by Annmarie Kent | infographic by Hannah Johnson

The dumpster creaks open and pungent aroma pours out over the cracked green plastic of the bin. It’s an almost sweet rotting stink that blankets a few dried-up tomatoes and a carton of smashed eggs. A puddle of an unknown liquid is slowly forming beneath the bin and a few maggots fall from the lid. This isn’t the most appetizing place to get groceries.

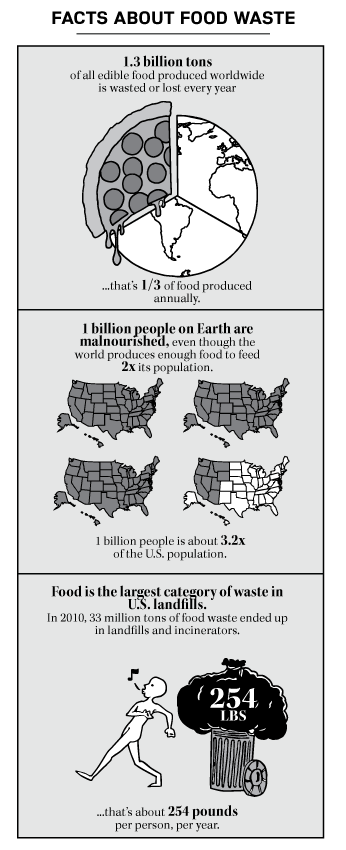

The United States Department of Agriculture estimates 133 billion pounds of food was thrown away in 2010 alone. That includes food tossed from restaurants, uneaten food discarded at home and expired food chucked by grocery stores and homeowners.

Bags of bread snowy with white mold and slightly slimy peppers may not be salvageable, but expired food is nothing for Western senior Emily Carlson, who licked the inside of a trash can on a dare. Carlson says she’s not squeamish — and it’s easy to see why.

“People can’t get over the heebie-jeebies, and I just don’t have them,” Carlson says.

Most expiration dates are conservative and some food can be eaten safely months after its “best by” date, yet every year about 40 percent of food ends up in landfills rather than stomachs.

While many people strictly adhere to expiration dates, throwing away their food in disgust when it reaches the shelf life, Carlson has no problem pushing the limit a little and eating expired goods — as long as they’re not too gross: no maggots, no mold.

TO EAT OR NOT TO EAT

Carlson spends her days working for an analytical firm that tests everything from drinking water to cow feces for pathogens such as salmonella, E. coli and listeria. These days she is testing the shelf life of mini cheesecakes, monitoring bacterial growth each day after their “best by” date.

So far, the little pink cakes are clean. Even days after their date they are safe — and Carlson is looking forward to eating them with her lunch tomorrow. While the desserts are cleared by the lab tests, Carlson says every company has different standards of freshness.

It is up to the consumer to eat safely. Expiration dates on most products are advisory only, meaning manufacturers guarantee the freshness and wholesomeness of their product up to the printed date provided that it has been properly handled, says Tom Kunesh of the Whatcom County Health Department.

Expiration dates are not legally required on food products with the exception of infant formula, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Food manufacturers must ensure their products are safe to eat, even if it is consumed past the “best before” date. However, manufacturers are not legally responsible for illness caused by eating spoiled foods.

Illnesses associated with food are spread mostly through handling rather than expiration dates. Of course, eating foods past their prime can be unpleasant. No one likes to bite into moldy bread or a mushy strawberry, but some expired foods don’t make people sick — they just taste bad.

“Some of the organisms that cause food spoilage will make foods smell bad, look bad, taste bad. You get slime, you get mold, they give off odors,” Kunesh says.

Expiration dates are not legally required on food products with the exception of infant formula, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

For example, a fresh head of lettuce could be washed on a farm with E. coli in the water. If it makes it past the farm without contamination, it still has to pass the distribution facility, which may house disease-carrying mice. At the store, it could be poorly refrigerated. At home, raw chicken in the fridge could drip on the lettuce, infecting it with salmonella. Even crisp, green lettuce fresh from the store can be a hazard if handled improperly, and the contamination is invisible.

“Foods that are contaminated with pathogens are not going to be easy to detect,” Kunesh says.

KEEPING FOOD ON THE TABLE

Most stores take the guesswork out of expired goods, rotating products and tossing food or donating it to a food bank as it reaches the “sell by” date. Organizations such as food banks also help limit the amount of food that enters the landfill — and help feed the United States Environmental Protection Agency’s estimated 49 million Americans without access to food.

The first food banks in the early 1970s were essentially groups of Dumpster divers rescuing discarded food from grocery stores and giving it to people in need, says Mike Cohen, executive director of Bellingham Food Bank. Food banks have evolved since then and Bellingham Food Bank serves more than 10,000 people each month.

The local food bank also started a gleaning program to collect excess food crops from farms. Last year they saved 200 pounds of produce from being tilled under the soil. Home garden produce also accounts for 50,000 pounds of food donations.

“We want it all — and that helps educate the community that we are about more than packaged food,” Cohen says.

The bank focuses on fresh foods, such as dairy, bread from local bakeries and produce from the farmer’s market. It also accepts canned goods, and expiration dates are not a concern. Cohen says that every once in a while a moldy product or spoiled food is distributed, but for the most part the food bank is pretty careful — and patrons select food for themselves.

And the food that isn’t in such good shape? The bank donates limp and wilting produce to farmers to use as livestock feed and compost.

Rescuing every last scrap of food from a lonely landfill future has a much higher purpose than some may realize. Discarded food breaks down and releases methane, a potent greenhouse gas. The EPA estimates landfills release 20 percent of all methane in the atmosphere, so keeping leftovers out of the trash has global consequences.

HOW TO NOT THROW UP

Some stores, such as Grocery Outlet and Deals Only sell expired food at a discount, saving people money and saving food from the trash. Grocery Outlet pulls all fresh dairy and meat from shelves at the products’ expiration dates. Products like processed cheeses, juice and smoked salmon are thrown away seven days after the printed date and dry grocery goods are given 30 days past expiration to sell.

Discount stores also often sell damaged products such as crackers in crunched boxes and products with misprinted labels. Just like expired goods, damaged goods are not harmful, Kunesh says. Except for damaged cans.

“Don’t buy cans that are severely dented. Don’t buy cans without labels. Don’t buy cans that are bulging,” Kunesh says.

When cans bulge, bacteria is growing inside the can, Kunesh says.

Denting and squishing cans can cause the seals to break, welcoming in dust spores that may contain pathogens such as botulism. Botulism is a foodborne bacteria that attacks the nervous system and can be fatal. According to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 145 cases of botulism are reported each year in the United States, mostly from home-canned and pickled goods and expired canned food.

Eating expired goods presents risks, but the key to staying safe is mostly in safe preparation. Kunesh’s top rules: wash hands, cook meat all the way through and don’t let sick people prepare food for others. Don’t leave cooked foods out overnight; that includes soup abandoned on the stove or the bit of mac and cheese left in the bottom of the pot.

And skip the Dumpster diving.

“You don’t know why that food was thrown away,” Kunesh says. He says a diver may think cottage cheese or deli pasta salad that is still cold is gold, but what if a clerk found a refrigerator that wasn’t working and the product is spoiled?

Kunesh points out that foods may mingle with less appetizing trash, such as restroom waste and chemical residues from cleaning products — even bleach. In case of an outbreak of infectious disease, the health department orders the contaminated food to be doused with bleach and then dumped. In Kunesh’s opinion, a Dumpster steal is not worth the risk.

But for Carlson, it’s all about the limit — finding that tipping point when food is no longer appealing. People come into contact with the germs crawling on Dumpsters every day, she says. Exposure to a little dirt and a little mold only helps build immunity in Carlson’s experience; Carlson hasn’t been sick in a year and has never had food poisoning. A green pepper plucked from the trash — in Carlson’s book that’s a healthy pepper and one more pepper that won’t end up in the landfill.