Sweet as Honey

The living history of Yiddish in Bellingham, Washington.

Story by Eva Bryner

It’s a beautiful sunny day and you’re walking through the streets of downtown Bellingham, Washington. As you walk, what do you hear? The lull of the bay, the ever-present seagulls overhead, an occasional train briefly filling the world with sound. You hear people talking, connecting, laughing. What language are they speaking? Maybe English, Spanish or Russian.

Floating through the breeze by David Schlitt’s home, you’d hear Yiddish.

Yiddish uses the Hebrew Alef-Beys (alphabet) and is most commonly spoken in the U.S. among East Coast Hasidic communities. While Yiddish has roots in German, variations of Yiddish exist in Spanish (called Ladino), Ukraine, Russian and many other languages. There are estimated to be between 500,000 and 1 million Yiddish speakers around the globe, with 155,582 living in the U.S. in 2013, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Warm afternoon sun peered through the window in Schlitt’s home office as he showed me a video of his 8-month-old son, Jacob, eating spaghetti in a high chair.

Schlitt, manager of special collections at Western Washington University, worked with the Judaica Archives and taught two quarters of Introduction to Yiddish prior to his current manager role.

His Introduction to Yiddish courses were filled with a mix of full-time Western students and community members eager to practice Yiddish.

“Sometimes the best I think I can do as an instructor is to spread enthusiasm and give people something you can hold onto and then build on if the opportunity arises,” Schlitt said.

He and his partner, Associate Professor and Endowed Chair of Jewish History Sarah Zarrow, both work at Western. They left their Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania home in 2017 to teach at the university.

“Pittsburgh was very new to me and it’s a place where the Jewish community has deep roots … everybody knows everybody going back a hundred generations,” Schlitt said. “And so, I never felt like I cracked it. Bellingham has been a place where people [are] more accustomed to people coming and going, it was very easy to kind of jump in.”

Schlitt’s parents were both second-generation Jewish immigrants and he grew up speaking and hearing Yiddish at home in Boston, Massachusetts. His vocabulary blended Yiddish and English, and there were many words he didn’t realize were Yiddish until studying the language later in life.

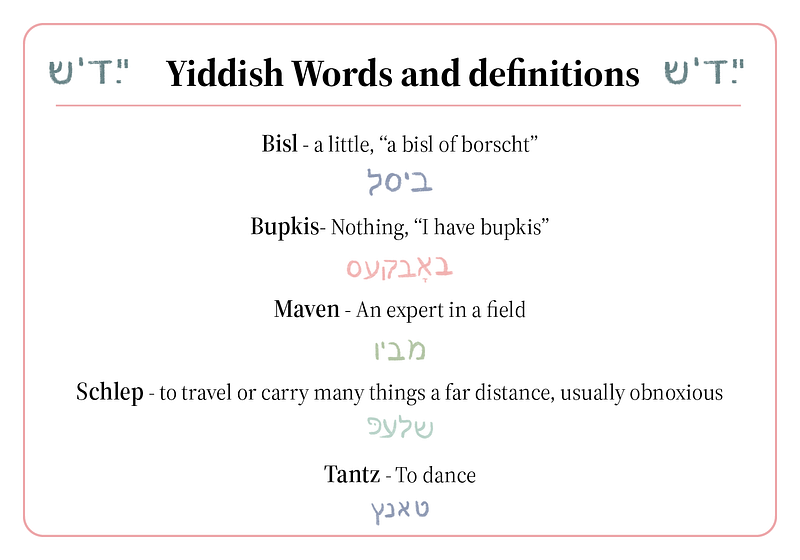

Words like “maven,” a Yiddish word for someone who is an expert or very knowledgeable, were embedded in his day-to-day life without second thought.

“I always thought it was an English word, and only later did I realize when I started studying Yiddish, that it’s actually a Yiddish word. [And another] Yiddish word is Loshn-Koydesh, meaning that it has even deeper roots emerging out of biblical Hebrew and Aramaic,” Schlitt said. “So, it’s a word with a long pedigree that I just figured was contemporary English.”

He came to study Yiddish as a form of rebellion against his modern Hebrew-focused schooling.

“I was like, ‘What we’re learning about in school in no way reflects my family life or my experience of Jewish life at home,’” Schlitt said.

Surrounded by walls of books in his office, Rabbi Avremi Yarmush of Chabad explained Yiddish’s complex origin.

“Hebrew is considered the holy tongue, the holy language,” Yarmush said. “So we don’t use the holy language for mundane chitter-chatter.”

Yarmush continued that Yiddish is a dialect mixed with local language and Hebrew words. In essence, it’s a language absorbed from those around it.

In the U.S., you’ll likely hear an American version of Yiddish being spoken. American Yiddish, sometimes called “Yinglish,” is a blend of Yiddish words into the English vocabulary, much like what Schlitt grew up hearing.

When asked to describe the history of Yiddish, Schlitt’s eyes lit up.

“Yiddish literature, critics and scholars have said it’s something that really was catalyzed by women readers,” Schlitt said. “And then there’s this idea [that] it is a woman’s language because it’s the Mama-Loyshen, it’s the mother tongue.”

Schlitt elaborated that as Yiddish grows and changes, like all languages, it becomes more complicated and interesting.

Yiddish at The Willows

Walking into The Willows, an assisted living community in Bellingham, you’re greeted by staff and residents. The earth tone carpet absorbs all sound in the space, and each Tuesday you can hear Yiddish conversations softly down the long hallway.

At the end of the hall is a large, open room filled with overstuffed couches and chairs. Yellow fluorescent lights tint the room, casting an orange hue on the floral arrangements that cover the tables.

The Willows reserve this space weekly for the Yiddish club. Usually, community members and a few residents stroll into the room. However, since the COVID-19 pandemic, these meetings have transitioned to Zoom.

In the club meetings, community members and residents gather to read, speak and share stories, poems and songs in Yiddish.

Among the members in the club is Maggie Weisburg. In her apartment, plants line the windowsill and photos from Weisburg’s life obscure her refrigerator door.

An original New Yorker, Weisburg has lived at The Willows for 12 years after crossing the country from Cleveland, Ohio to be closer to family.

Two bright orchids sit in Weisburg’s living room — purple and white, both gifts from her birthday in January. She feeds them two ice cubes a week and noted, to her surprise, they are still blooming.

She lived at The Willows for five years before hearing about the Yiddish conversation group and has attended regularly since.

“It’s a sort of a social group where we just talk Yiddish and exchange experiences,” Weisburg said. “There used to be an older couple who lived in Brooklyn, and so often there was an exchange of memories of growing up in Brooklyn and New York and what life was like in those days.”

Her parents both immigrated to the U.S. — her father from Lithuania and her mother from Russia.

Throughout her childhood, Weisburg’s parents called her Hildele, using the common Yiddish diminutive -ele.

Though she grew up hearing Yiddish, Weisburg always thought of it as a language for the elderly, representing “old-fashioned ways.”

“For a long period of my life, it was Hebrew that I focused on,” Weisburg said. “I didn’t come back to Yiddish actually until I moved to The Willows and discovered the Yiddish group, which I joined out of curiosity. I still was not particularly interested in Yiddish.”

She joined the group to find a sense of “heymishkeit” — the feeling of being at home with Jewish people.

“Being with Jewish people had a certain kind of familiarity that felt good,” Weisburg said. “It’s been a positive experience, and I’ve been learning Yiddish and appreciating more Yiddish as a language. I’m overcoming some of my old prejudices that it’s a language of old people.”

Weisburg turned 97 this past year. She is reminded of her long life each time she feeds her orchids.

The Sweetness of Honey

When teaching children the Hebrew Alef-Bet, adults traditionally put honey on the letters so children will associate the sweetness of honey with the sweetness of learning and speaking.

As reported from the U.S. Census Bureau, from 1990 to 2011, the number of Yiddish speakers in the U.S. declined by just over 52,000. By 2013, these same numbers were down by 5,386.

However, in recent years there’s been a resurgence of Yiddish in pop culture. You can learn how to speak Yiddish on Duolingo and hear it on television shows like “Unorthodox.”

So, what does the future of Yiddish look like?

According to Schlitt, it depends on who does the work.

“Yiddish is definitely going to continue on among the ultra-Orthodox, because this is used as a way to keep the world out,” Schlitt said. “I’m feeling more relaxed about Yiddish’s future than I have for a while.”

When I asked Yarmush the same question, he paused for a moment. He explained how he tried speaking to his oldest son in Yiddish exclusively, and at some point gave up.

“You know, Yiddish might die with me when it comes to my children,” Yarmush said. “They live in an environment where I want them to have a second language, but in levels of importance, the development of their Hebrew skills is more important to me.”

Yarmush taught his youngest son and daughter Hebrew and focused their language education on the language they will be studying and praying in.

“I don’t know if I’m making a mistake or not, but I don’t know what the future [holds],” Yarmush said.

This sentiment is echoed by Schlitt, who has started speaking to his son Jacob in Yiddish. He’s impassioned about teaching him the language, but wants him to forge his own path toward it.

“The best thing you can do is to live with a type of integrity and authentic interest that you can then show by example,” Schlitt said.

He joked, “We’re just trying to keep the floors relatively clean.”

On Schlitt’s phone screen, spaghetti sauce dribbles down Jacob’s chin.